News

Preview Bring Them to Zion: The 1856 Handcart Emigration Organization, Leadership, and Issues June 27 2025

Read a preview of Bring Them to Zion: The 1856 Handcart Emigration Organization, Leadership, and Issues.New Year's Ebook Flash Sale December 29 2020

As we welcome 2021, we are pleased to offer discounted prices on select ebooks on scripture, doctrine, and community. This sale runs from January 1–4 and is available for both Kindle and Apple ebooks.

Sale ends Monday, Jan 4.

Doctrine| Scripture | ||

|

$17.99 |

$27.99 |

$22.99 |

|

$18.99 |

$22.99 |

$23.99 |

| Doctrine | ||

|

$30.99 |

$17.99 |

$9.99 |

|

$26.99 |

$16.99 |

$18.99 |

| Community | ||

|

$18.99 |

$14.99 |

$18.99 |

|

$23.99 |

$18.99 |

$9.99 |

FLASH SALE: Award-winning Latter-day Saint books — 30% off retail prices! September 23 2020

We are proud of our authors and books! Expand your collection of biographies and narrative histories, anthologies and personal essays, and scripture scholarship with these award-winning titles below. Now 30% off through the end of September.

Sale ends Wednesday, 9/30/2020*

|

2020 Best Biography, JWHA $24.95 |

2018 Best Anthology, JWHA $22.95 |

2017 Best International History, MHA $39.95 |

|

2016 Best Literary Criticism, AML $18.95 |

2016 Best Religious Non-fiction, AML $20.95 |

2016 Best Biography, JWHA $39.95 |

|

2015 Best Religious Non-fiction, AML $34.95 |

2015 Best Book Award, MHA $32.95 |

2015 Best International History, MHA $24.95 |

|

2014 Best Religious Non-fiction, AML $20.95 |

2014 Best International Book, MHA $34.95 |

2013 Best International History, MHA $29.95 |

|

2012 Best Biography, MHA $31.95 |

2012 Best Criticism Award, AML $34.95 |

2011 Best Book Award, MHA & JWHA $34.95 |

|

2007 Best Book Award, JWHA $31.95 |

2003 Best Biography, MHA $32.95 |

1988 Best Book Award, MHA $31.95 |

*For international print orders, email order@koffordbooks.com. Subject to available supply.

Q&A with Richard G. Moore, editor of The Writings of Oliver H. Olney April 1842 to February 1843 — Nauvoo, Illinois May 11 2020

The handwritten papers of Oliver Olney are housed in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University and are made available in published form for the first time. They offer historical researchers and interested readers of the early Latter-day Saint movement a unique glimpse from the margins of religious society in Nauvoo. Olney’s writings add light to key events in early Mormonism such as rumors of polygamy, the influence of Free Masonry in Nauvoo, plans to migrate westward to the Rocky Mountains, as well as growing tensions with disaffected church members and rising conflict with Nauvoo’s non-Mormon neighbors.

Q: How did you discover Oliver Olney and what made you decide to transcribe his writings?

A: Some years ago, I was looking for a topic for a paper to present at the John Whitmer Historical Association Conference. The theme that year had to do with the divergent paths of belief that some early converts to the Restoration took. I remembered reading a Times and Seasons editorial called “Try the Spirits” that mentioned a number of people who had left the church founded by Joseph Smith after receiving their own revelations. Returning to that article, I found the name of Oliver Olney. I didn’t know if there was enough information about him to write a paper but was surprised to discover that there were over four hundred-fifty pages handwritten by Olney housed at Yale. I obtained a copy of his writings, transcribed much of what he had written, and was able to present a paper at the conference. After my presentation, Greg Kofford approached me and said that he would like to publish all of Olney’s writings. I began the work of transcribing everything that I could find written by Oliver Olney.

Q: Can you describe Oliver Olney? Who was he and why is he a significant source for the Nauvoo era?

A: Oliver Olney joined the Latter-day Saint movement in 1831 while living in Ohio. He and his wife moved to Kirtland where he became president of the Teachers Quorum. His wife was the daughter of John Johnson and the sister of Luke and Lyman Johnson, two of the Restoration’s first apostles. He and his wife later moved to Missouri and experienced the anti-Mormon violence there. They eventually moved to Nauvoo. Oliver was on a mission to the Eastern States when his wife, who had remained in Nauvoo, passed away. Returning from his mission, he became disaffected with the Church and its leaders. However, after being excommunicated, he remained in Nauvoo and wrote down what he observed taking place there. His writings are first-hand accounts, albeit biased, of a person living in Nauvoo during the early 1840s.

Q: Can you give us a brief overview of how this documentary history is organized?

A: Olney wrote something of a dated journal for several years. However, he often wrote more than one version for a particular date. His papers were in numbered folders at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Unsure which version Olney wrote in what order, the book is arranged by date, in order of the folder in which they appear. In other words, if he wrote three entries for June 3, they would be arranged like this: June 3 [folder 2], June 3 [folder 5], June 3 [folder 7]. Also included in the book are two complete booklets that Olney had published.

Q: What are a few big takeaways that we get from Oliver’s writings?

A: Olney had heard rumors spreading around Nauvoo about polygamy among Church leaders and he wrote about what he had heard. He also noted the establishment of a Masonic chapter in Nauvoo. He said that he was unsure about the virtue of Masonry and claimed that the Mormon version of Masonry being practiced in Nauvoo was an immoral thing—even connecting the Danites to what he referred to as “new-fangled” Masonry. Olney also viewed the formation of the Relief Society as Masonry for women. In 1842 he stated that the Mormons were already making plans to move to the Rocky Mountains and establish a kingdom there.

Q: Can you share a few issues Olney had with church leadership? Why do you think he remained in Nauvoo after his excommunication?

A: Some of the biggest issues that Olney had with church leadership were financial. At the time he was writing, he viewed himself and others in Nauvoo as being poverty stricken while church leaders lived in luxury. He viewed tithing and the law of consecration as gouging the Saints for the benefit of church leaders. He was also troubled by rumors of plural marriage being practiced by church leaders. He felt that the Restoration had gone off the track. Olney did stay in Nauvoo for several years after his excommunication, even though he said in a few of his writings that he believed his life to be in jeopardy. I believe he stayed at first because he thought a reformation could take place within the Church and he saw himself as the person who could help that reform take place. After coming to believe that there was no hope for church leaders to repent, I believe he stayed to get more dirt or ammunition for his attack on Mormonism.

Q: Can you give us a little insight into Olney's claimed visions and heavenly visitations?

A: Olney recorded visits of heavenly messengers, giving him instructions for building God’s kingdom on the earth in preparation for the Second Coming of Christ. Prominent in these visits were the Ancient of Days, twelve prophets from Old Testament times that would meet with him quite often. Olney claimed that these twelve, who lived on the North Star, called him to choose a new Quorum of the Twelve. He was ordained to a special priesthood by them and was told where to find a buried Nephite treasure to fund the building of the kingdom. He also said that he was visited several times by the deceased apostle, David W. Patten.

Q: Do we know what became of Oliver Olney after Nauvoo?

A: Prior to leaving Nauvoo, Olney remarried a Mormon woman, a believer who was assistant secretary in the first Relief Society. Very little is known about him after he left Nauvoo. He returned to Nauvoo after the death of Joseph Smith and, according to his own writing, hoped to be able to receive his endowment in the Nauvoo Temple. I was unable to find anything about him after that except the assumption that he died in Illinois sometime in 1847 or 1848.

Richard G. Moore

May 2020

Church History and Doctrine Sale: 30% off Select Titles in Print and Ebook April 15 2020

Brush up on your studies of Latter-day Saint history and doctrine with informative and insightful research and explorations. Now 30% off for both print and ebook through Memorial Day.*

Sale ends Monday, 5/25/2020

|

$32.95 |

$34.95 |

$29.95 |

|

$32.95 |

$19.95 |

$31.95 |

|

$26.95 |

$24.95 |

$30.95 |

|

$31.95 |

$14.95 |

*For international print orders, email order@koffordbooks.com. Subject to available supply.

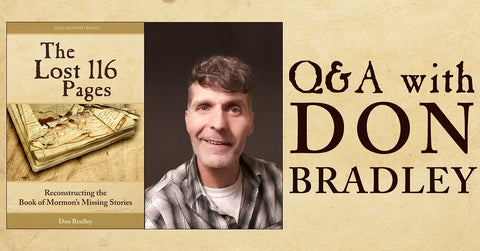

Q&A with Don Bradley, author of The Lost 116 Pages: Reconstructing the Book of Mormon's Missing Stories December 09 2019

| Download a free sample preview | Order your copy |

For readers less familiar with the "lost 116 pages" can you provide a brief synopsis of what they were and how they became lost?

After Joseph Smith dictated to scribes the first four and half centuries of the Book of Mormon’s chronicle of ancient Jewish settlers in the New World (the Nephites), the manuscript of this account was borrowed by the last of those scribes, Martin Harris. The manuscript later disappeared from Harris’s locked drawer and has been lost to history ever since. The current Book of Mormon text is therefore incomplete, substituting a shorter account for this lengthy missing narrative.

Can you piece together what most likely happened to this lost early manuscript? Does the standard narrative that Lucy Harris likely destroyed them hold up? If not, why and what other possibilities should we consider?

When the manuscript disappeared, Martin Harris initially suspected his wife of the theft. Lucy Harris had been skeptical of her husband’s investment in the book and would have had motive to interfere. Lucy Harris has been regarded as the prime suspect in the theft since the late 1800s, and it has been widely presumed that she burned the manuscript. However, the explanation that Lucy Harris burned the manuscript was first proposed as only a speculative possibility a quarter-century after the fact, but the dramatic image of the disgruntled wife throwing the pages into the flames quickly caught fire and became increasingly popular with time. The further the historical sources get from the actual theft, the more likely they are to tell this story, indicating that it was the story’s sensationalism, rather than its accuracy, that led to its popularity. The first person to have suspected Lucy Harris of the theft, her husband Martin, abandoned this theory when he learned that his estranged but devout Quaker wife had denied on her deathbed knowing what happened to the pages.

The presumption that Lucy Harris stole the pages, acted alone in doing so, and burned them has prevented investigators from looking closely at other suspects, including a number of people who had previously attempted to steal other documents and relics associated with the Book of Mormon. Former treasure digging associates of Joseph Smith had attempted several times to steal the original Book of Mormon—the golden plates. And Martin and Lucy Harris had a son-in-law, a known swindler, who once stole the “Anthon transcript” of characters copied from the plates. Fixating on Lucy Harris as the only possible thief has blinded inquirers to noticing these obvious suspects.

Despite the widespread presumption that Lucy Harris was guilty of taking and burning the manuscript, the manuscript’s ultimate fate is an open question.

You assert that the lost early manuscript might have been longer than 116 pages. Can you provide some reasoning for this? Can you also speculate on how long they may have been?

The number given for the length of the lost manuscript—116 pages—exactly matches the length of the “small plates” text that replaced that manuscript. This coincidence has led several scholars, beginning with Robert F. Smith, to propose that the length of the lost manuscript was actually unknown and the 116 pages figure was just an estimate based on the length of its replacement.

While we can’t know for sure the length of the lost manuscript, unless it turns up, we can do better than just guessing at its actual length, because we have several lines of evidence for this, all of which converge on a probable manuscript size. Joseph Smith reported that Martin scribed on the lost manuscript over a period of 64 days, which, given Joseph’s known translation rate would have produced a manuscript far larger than 116 pages. In line with this, Emer Harris, ancestor to a living Latter-day Saint apostle and brother to Martin Harris, reported at a church conference that Martin had scribed for “near 200 pages” of the manuscript before it was lost. A later interviewer recounted Martin himself reporting a similar scribal output when stating what proportion of the total Book of Mormon text he recorded. Since Martin was not the only scribe to work on the now-lost manuscript but, rather, the fifth such scribe, the manuscript as a whole would have been well in excess of the nearly 200 pages produced by Martin, likely closer to 300 pages. Other lines of evidence within the existing Book of Mormon text point to a similar length for the lost portion.

What sources are used in this book to identify what was in the Book of Mormon's lost 116 pages?

To reconstruct the Book of Mormon’s lost stories this book makes use of both internal sources from within the current Book of Mormon text and external sources beyond that text. Internal sources from the Book of Mormon include, first, accounts from the narrators of the small plates of Nephi, which cover the same time period as the lost portion of Mormon’s abridgment, and, second, narrative callbacks in the surviving remnants of Mormon’s abridgment that refer to the lost stories. External sources used in the reconstruction include statements in the earliest manuscripts of Joseph Smith's revelations describing and echoing the lost pages, statements by Joseph Smith reported by apostles Franklin D. Richards and Erastus Snow, an 1830 interview granted by Joseph Smith, Sr., a conference sermon by Martin Harris’s brother Emer Harris, and reports by several other early Latter-day Saints and friends of Martin Harris.

Can you provide a few examples of how your research into the lost early manuscript has increased your awareness of a Jewish core in the Book of Mormon text?

The research that went into this book has disclosed to me a Jewishness to the Book of Mormon that I could never have imagined. Through the lens of the sources on the lost manuscript, we can see the Jewishness in the Book of Mormon from the very start: according to Joseph Smith, Sr., the lost pages identified the Book of Mormon as beginning with a Jewish festival, namely, Passover. This Jewishness is particularly striking in the sources on the lost manuscript’s narrative of the book’s founding prophets Lehi and Nephi. Their narrative begins in that of the Hebrew Bible, at the start of the Jewish Exile. The recoverable lost-manuscript narratives of Lehi and Nephi show them seeking to build a new Jewish kingdom in the New World systematically parallel to the pre-Exile Jewish kingdom in the Old World. Having lost the biblical Promised Land, sacred city, dynasty, temple, and Ark of the Covenant, they set about re-creating these by proxy.

This Jewishness in the Book of Mormon is paralleled by a distinct Jewishness of the Book of Mormon’s coming forth. Reconstructing a chronology of the several earliest events in the Book of Mormon’s emergence shows every one of these events to have been keyed to the dates of Jewish festivals. In ways not previously appreciated, the Book of Mormon is a richly and profoundly Judaic book.

In your book, you discuss temple worship among the Nephites. Can you summarize some of your findings?

Temple worship stands at the center of Nephite life and of the Book of Mormon’s narrative. The early events of Nephite history, as chronicled in the present Book of Mormon text and fleshed out further in the sources on the book’s lost manuscript, all build toward the ultimate goal of re-establishing Jewish temple worship in a new promised land. Re-establishing such worship required constructing a system closely parallel to that of Solomon’s temple. To meet the requirements of the Mosaic Law, the Nephites would have needed substitutes for the biblical high priest and Ark of the Covenant, with their associated sacred relics. Accordingly, the Nephite sacred relics—the plates, interpreters, breastplate, sword of Laban, and Liahona—systematically parallel the relics of the biblical Ark and high priest, showing how closely temple worship in the Book of Mormon was modeled on temple worship in the Bible.

In what ways are the doctrines in the early lost Book of Mormon manuscript reflected in the doctrines of early Mormonism?

Earliest Mormonism has sometimes been understood as primarily a form of Christian primitivism, the New Testament-focused nineteenth-century movement to restore original Christianity. Yet already when we explore the earliest Mormon text, the lost portion of the Book of Mormon, we find a whole-Bible religion, one weaving Christian primitivist, Judaic, and esoteric strands into a distinctively Mormon restorationist tapestry of faith.

The Book of Mormon’s focus on the temple is also very Mormon. Temple worship among the Nephites not only echoes ancient Jewish temple worship, but it also anticipates temple worship among the Latter-day Saints. The recoverable narratives of the Book of Mormon’s lost pages portray the Nephite temple as not only a place in which sacrifices are performed but also one in which higher truths are taught in symbolic form, human beings learn to speak with the Lord through the veil, and people can begin to take on divine attributes.

What are you hoping readers will gain from your book?

This book’s earliest seed was my childhood curiosity about the Book of Mormon’s lost pages. That seed grew in adulthood when I realized how knowing more about the Book of Mormon’s lost pages could illuminate its present pages. On one level, this new book is a book about the Book of Mormon’s lost text, pursuing the mystery of what was in the lost first half of Mormon’s abridgment. On another level, this is a book about understanding more deeply the Book of Mormon text we do have, since the last half of any narrator’s story is best understood in light of the first half. Researching what can be known about the lost manuscript has helped me to more fully recognize the Book of Mormon’s richness, understand its messages and meanings, and grasp its power as a sacred text. My hope is that recapturing some of the long-missing contexts behind our Book of Mormon will also expand others’ understanding of and appreciation for this remarkable foundational scripture of Latter-day Saint faith and inspire readers to delve deeper into the Book of Mormon.

Don Bradley

December 2019

Christmas Gift Sale: 30% off select titles! November 29 2019

Christmas Gift Sale: 30% off select titles*

Looking for the perfect gifts for the book lover in your life? Get 30% off select titles now through Dec 18.

**Free pickup is available for local customers. See below for details.**

Sale ends Wednesday, 12/18/2019

|

$20.95 |

$21.95 |

$27.95 |

|

|

$26.95 |

$21.95 |

$19.95 |

|

|

$20.95 |

$27.95 |

$25.95 |

|

|

$26.95 |

$34.95 |

$34.95 |

|

|

$20.95 |

$19.95 |

||

|

$34.95 |

$36.95 |

$29.95 |

|

|

$34.95 |

$15.95 |

||

|

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

|

|

$49.95 |

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

|

|

|

COMPLETE SET $249.70 |

FREE PICKUP FOR LOCAL CUSTOMERS

Enter PICKUP into the discount code box at checkout to avoid shipping and pick up the order from our office in Sandy, Utah.

Pickup times available by appointment only. Email order@koffordbooks.com to schedule your pickup time.

*Offers valid for U.S. domestic customers only. Limited to available supply.

Q&A with Aaron McArthur and Reid L. Neilson for The Annals of the Southern Mission June 24 2019

| Download a free sample of this book | Order your copy |

Q: When did this project begin and how did you two connect?

A: [Aaron] The project began around 2004 when I was a graduate student at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. While working on my master’s thesis on the significance of tabernacles in the development of LDS communities, I discovered the Annals. That exposure came at Special Collections at BYU, where they had essentially a photocopy of the record. Many of the copies were of very low quality. When you consider that there was no index, it made them very hard to work with. Despite the problems involved with accessing the record, I realized that it was a gold mine of information.

To support my research agenda for my dissertation, the UNLV History Department used a sizable portion of their yearly book budget to purchase a $1,000 collection of scanned documents from the Church archives, which included the Annals. Given what an incredible resource the Annals are, I was amazed that they were so hard to access and resolved to rectify that situation. While working on my dissertation, I undertook a detailed transcription from the scans the library purchased. When I needed a break from the dissertation, I relaxed by transcribing.

Reid contacted me in my last semester of graduate school about working together to bring the Annals to print. He brings a vast amount of experience and resources to the table, and I was very glad to work with him.

Q: What challenges (if any) did you face while compiling this volume?

A: [Aaron] The biggest challenge with this project has simply been time. I did the bulk of the transcription while writing my dissertation and working full-time at UNLV Special Collections. Once the transcription was complete, I knew that we needed two independent verifications and we would eventually need an index. Arkansas Tech approved a professional development grant to pay for students to assist in the process. One of these students helped finish one verification even after grant funds were exhausted. I was very grateful that Reid took care of the index.

Q: Who was James Bleak and what makes his annals so valuable for historical research?

A: James Bleak was the historian for the Southern Mission. What makes the Annals so amazing is how he went about fulfilling his duties as a historian. Firstly, he created a sizable archive of records as events happened. When he actually started writing the history, he had decades of records to work with instead of having to conduct research. Second, is when he was writing, he was careful to include an in-text citation whenever he quoted sources. As a practicing historian, I love that I can tell what text belongs to who. Third, he quoted huge numbers of records in their entirety, not just selections that promoted his narrative. As a concise narrative, it is a 2200+ page nightmare, but it is an absolute goldmine for historians, genealogists, etc.

Q: What do we learn from the Annals about Latter-day Saint pioneer relations with Native Americans?

A: There are some major things that the Annals have to offer in regard to relations with Native Americans. The first is that it covers such a long period of time. This allows us to see some longer-term interaction patterns. This is especially important because those interactions were complicated by the fact that the Saints in southern Utah were interacting with Southern Paiute, Navajo, Ute, and Hopi, each of which had their own internal politics that influenced those interactions.

Overall, Brigham Young’s attitude towards Native Americans was that it made more sense to “shoot them with biscuits” than fight with them. Compared to most groups of white settlers, the Saints had much better relations with Native Americans in general. The Annals, unfortunately, has some very good examples of how some of those interactions went wrong.

Q: What were some of the struggles that pioneers faced in settling southern Utah?

A: Any time people build communities from scratch, there are going to be lots of struggles. The one that stands out the most to me for the Saints in southern Utah is their fraught relationship with water. There is a saying in the West that “whiskey is for drinkin’, and water is for fightin’ over.” The Saints didn’t drink whiskey, so that only left water. This is not to say that they were always fighting about it, but it was clearly never far from their minds. All of the settlements in the Southern Mission were in the desert, and all were reliant on agriculture. Getting enough water for crops was a constant challenge, except for when there was too much water that was washing out those crops that the irrigation works that fed them.

Q: What role did spiritual matters play in the actions and decisions of the southern Utah pioneer settlers?

A: As far as the Annals are concerned, spiritual matters were the things that mattered. You need to recognize that Bleak's position as historian was in an ecclesiastical organization, so the kinds of records he collected and used were influenced by that. Evidence indicates, however, that the average settler was similarly motived by spiritual matters. What indicates that to me is that ecclesiastical leaders were consistently elected or chosen for secular leadership positions.

Q: For each of you, what was one of your big takeaways from the Annals?

A: [Aaron] I have a few takeaways from the Annals project. The first is that you can accomplish some very cool things if you just keep plugging away on it. I worked on the project for nearly fifteen years. Second, you can never have too many friends. It is amazing how many people will jump in and help finish a worthy project if they are given the opportunity. Finally, Bleak’s work inspires me as a historian. I can only hope that more than a century from now that people will look at histories that I have written and find them as worthy as Bleak’s work is today.

[Reid] That James Bleak was so committed to getting the history of his people down in ink. That he was thinking generations ahead of his contemporaries who were barely eeking out a living and in survival mode. But he was looking to the future and appreciated that it was up to him as the designated historian to keep a record, just as the LDS scriptures commanded him to do (D&C 21:1). I marvel at his persistence and am grateful for his attention to detail.

Aaron McArthur and Reid L. Neilson

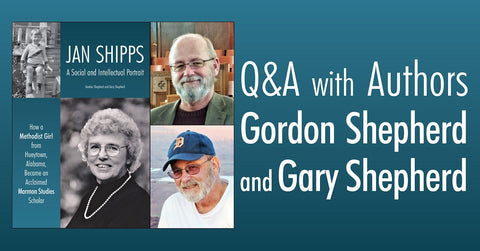

Q&A with Gordon and Gary Shepherd for Jan Shipps: A Social and Intellectual Portrait May 27 2019

| Download a free sample preview | Order your copy |

Q: For those unfamiliar with Jan Shipps, what can you tell us about her and why she is important within Mormon studies?

A: In the mid-to-late 1970s, Jan Shipps began to emerge as an important new scholarly voice in Mormon history circles. She was not a Latter-day Saint (LDS), and she was a woman claiming the right of place in a field dominated by men. Yet she proved she could more than hold her own with the male scholars who constituted the inner circles of both the LDS-based Mormon History Association and its RLDS counterpart, the John Whitmer Historical Association. Her scholarly work was fresh and insightful, she rapidly ascended to positions of leadership and made meaningful organizational contributions within both groups, and she helped mediate differences between scholarly proponents of these two historically antagonistic camps of Mormonism. These men respected, accepted, and encouraged her. By the early to mid-1980s Jan’s reputation for unbiased and nonpolemical writing and speaking on Mormon topics also earned her the confidence of both the national media (who consulted her constantly for her take on news stories related to Mormons and the LDS Church) and upper echelon authorities of the LDS Church (who gave her unprecedented access to them and their views on the same topics). She was simultaneously instrumental in persuading many prominent religious studies scholars and American Western historians of the significance of Mormonism as a case study in their own disciplines that had previously trivialized or dismissed the serious study of Mormons, past and present. Her 1985 book, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition, received widespread critical acclaim and cemented her reputation as an authoritative scholarly interpreter of both Mormon history and contemporary Mormon culture. In succeeding years, her reputation and influence remained strong, and she continued—well into her eighties—as an active scholar, mentor to a new generation of women historians, and as an organizational participant within the expanding field of Mormon studies that she had herself helped to legitimate.

Q: What made you decide to write a book about her?

A: Although the two of us are only marginally connected to Mormon history circles, we had known Jan professionally for a number of years. This connection was due mostly to Jan characteristically reaching out to people like us who demonstrated a manifest interest in the scholarly study of Mormonism from other perspectives (sociology in our case), and we were well aware of her important contributions to the related fields of Mormon history and Mormon studies. Five years ago, she invited us to her home in Bloomington to confer for two days on a then-current project of ours that she found interesting while soliciting our views on a current project of her own. Our natural inclination is to ask a lot of biographical questions in the process of interacting with other people, and we quickly became a lot more familiar with her as a person on this occasion (and on others that subsequently followed). We reflected on what a remarkable transformational story her life presented—a life that merited telling at least in terms of how she had transitioned from unpromising beginnings growing up in Depression-era Alabama, to entering into adulthood as a post-World War II housewife and mother without a college degree, to eventually emerge, in middle age, as a pre-eminent scholar of Mormonism. It didn’t take long for such reflections to crystallize into a conviction that we could, should, and would attempt to tell her story.

Q: Can you briefly explain what kind of analysis this book provides beyond a typical biography?

A: We have not tried to write a thorough, conventional biography that explores every known pertinent fact about our subject in detailing the full arc of her life. We call our project a “social and intellectual portrait,” laying out a basic summary of what we perceive as life-shaping experiences, personal characteristics, role model and mentor relationships, and environmental circumstances—from early childhood through mid-adulthood—that shaped, prepared, and eventually propelled Jo Ann Barnett into improbable prominence as Jan Shipps, the “outsider-insider” Mormon observer par excellence. We also make a detailed argument that Jan’s Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition merits inclusion with Fawn Brodie’s No Man Knows My History, and Juanita Brooks’s Mountain Meadows Massacre as the three most impactful scholarly books thus far written on Mormon topics. Hand in hand with this argument, we also show how Jan’s deep and extensive participation in professional academic circles—both Mormon and non-Mormon—significantly advanced the stature of Mormon studies as a legitimate and important field of scholarly inquiry. Finally, we suggest how Jan’s own evolving religious beliefs and attitudes regarding contemporary feminist issues have interacted with her understanding and interpretation of Mormonism.

Q: Give us a brief look into Jan Shipps background. When did she decide to start researching and studying Mormonism and what prompted her?

A: Jan arrived in Logan, Utah in the summer of 1960, accompanying her husband, Tony, who had just been hired as the new assistant head librarian at Utah State University. Jan was 30 years old, mother of an 8-year old son, had a number of credits earned at women’s colleges in Alabama and Georgia (but had not completed an undergraduate degree) and knew virtually nothing about Mormons. But she was naturally tolerant and curious about Mormons and immediately began to read as much as she could find about them, including Leonard Arrington’s Great Basin Kingdom (Arrington was then professor of history at USU but on sabbatical at the time). Jan registered for classes at USU to obtain teaching credentials so she could supplement the meager family income. She changed her degree from music to history to facilitate this aim and serendipitously took a historiography course from visiting professor, Everett Cooley (who was temporarily filling in for Arrington). Cooley recognized Jan’s potential as a student and gave her an assignment to research and write about a Mormon topic from primary source materials to which Cooley had access. Jan succeeded brilliantly in this assignment while pursuing a self-directed crash course in readings on Mormon history. When Tony was hired for a new library position the subsequent year at the University of Colorado, Jan opted to enroll in a master’s degree program in history at UC, again with the intention of gaining additional required credentials to become a public-school teacher. Given her recently acquired experience at USU, she chose to write a course paper on a Mormon topic and produced what later became her first published article: “Second Class Saints,” an analysis of Black Mormons. She followed up this paper by expediently writing on another Mormon topic for her master’s thesis, “The Mormons in Politics. 1839–1844.” When Jan was subsequently (and unexpectedly) encouraged by CU history faculty to continue graduate studies as a Ph.D. student, she was by now committed by intellectual passion and commitment (and not just convenience) to write her dissertation on “The Mormons in Politics: The First Hundred Years,” and to continue pursuing a scholarly focus on Mormon topics.

Q: Above, you heralded Jan Shipps’s 1984 book, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition, as one of the most significant books in Mormon studies. For readers who are less familiar, can you give a brief description of her book and offer a few reasons for its significance?

A: In spite of Jan’s subtitle, “The Story of a New Religious Tradition,” the story she tells is not a conventionally detailed or comprehensive narrative of Mormon history and the organization of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Jan’s approach is to instead understand the rise of nineteenth-century Mormonism using comparative, analytical, and theoretical religious studies methods. While the seven chapters of her book can all be read as separate essays, combined they sustain a coherent thesis about the relatively rare emergence and organizational transformation of a new religious tradition in the context of nineteenth-century American history and religious culture. Jan’s central thematic argument requires that we not only consider early Mormonism in the context of American religious history but that we also see it in broader historical comparison to the rapid rise of Christianity as a new religious tradition from its initial incarnation as a Jewish sect. By new religious tradition, Jan means explicitly that the theological beliefs and associated religious symbols, rituals, and religiously mandated practices diverge so much from the parent religious tradition that they burst the bounds of the old and must be grasped as something fundamentally new and distinctive.

The insights about the emergence and subsequent development of Mormonism that Jan produced began with an analogy to early Christianity. Analogies are heuristic devices that stimulate possible solutions to unresolved problems or debated questions. The debated questions about Mormonism are: What kind of religion is it? Is it Christian or non-Christian? How and why did it emerge and spread so rapidly when and where it did in nineteenth-century America? How did it not only survive furious resistance as a perceived Christian heresy but ultimately flourish to become a rapidly expanding international religion in the twentieth century? And in the process of doing this, what kind of religion did it consequently become for its adherents both at home and abroad? These are the kinds of questions that concern Jan’s analysis of Mormonism and not merely a descriptive, chronological account of its history and most prominent leaders.

In short, Mormonism is not written to be either faith promoting or faith debunking. It is not a conventional history. It is a comparative and analytical treatise that positions Mormonism within larger historical, cultural and social contexts. It commanded the attention and respect of eminent scholars and conferred increased recognition and legitimacy on the scholarly field of Mormon studies.

Q: You mentioned that Jan Shipps became a go-to expert for the national media whenever they covered a Mormon-related topic. How did Jan achieve this status? And how did her national media presence affect her relationship with the leaders of the LDS Church?

Jan not only became deeply involved with “insider” LDS and RLDS scholarly organizations (The Mormon History Association and the John Whitmer Historical Association), she also presented and published her work on Mormonism in a number of nationally prestigious outlets while simultaneously assuming active leadership roles in the professional organizations that sponsored these same scholarly conferences and journals (e.g., The National Historical Society, the Western History Association, the Center for American Studies, and the American Academy of Religion, among others). Prominent participation in these organizations gave national exposure to her scholarly work and advocacy of Mormon studies and garnered the attention of the media at a time that coincided with escalating interest in Mormons and the LDS Church due to such issues as Blacks and the priesthood, the Equal Rights Amendment, the Hoffman bombings, and the rapid growth and increasing influence of the LDS Church and prominent individual Mormons around the world. Given her growing reputation in national scholarly circles, It didn’t take long for the media to discover Jan as a non-Mormon expert on Mormons, who could provide unbiased but authoritative information and analysis on these and many other issues of interest. At the same time, through both local and national network sources, LDS Church officials reciprocally came to appreciate Jan’s unflagging promotion of detached but non-polemical scholarship on Mormon subjects. This appreciation was particularly facilitated through the savvy efforts of LDS Church Director of Press Relations and Public Communications, Jerry Cahill, to arrange Jan’s access to Church leadership as a mutually trusted bridge between them and national news outlets.

Q: How did Jan's Methodist faith evolve through the years that she studied Mormonism? How do you feel her religious tradition affected her writings on Mormonism?

A: Jan grew up as a dutiful, simple believer but a not very pious Methodist. The most important religious principles she acquired from her childhood were tolerance of others’ religious beliefs and the notion that the primary purpose of religion was to help people in need. Her religious tolerance has matured into an active curiosity about diverse religious perspectives and genuine respect for the legitimacy of religious beliefs that are sincerely held in different religious traditions. This outlook came into its maturity as she studied Mormon history, beliefs, and practice—all completely unknown to her at the outset of her academic career. Jan’s detached, analytical, but respectful treatment of Mormonism’s beginnings and development as a new religious tradition was a hallmark of her early, acclaimed work. Ongoing, increased contact with ordinary Mormons, Mormon scholars, and LDS Church leaders have deepened her appreciation of Mormonism as a valid religious tradition. But she is not a convert to Mormonism and remains committed to the organizational expression of her Methodist beginnings. However, Jan’s private religious beliefs are more complicated, diverse, and universal than those proclaimed either by conventional Methodism or Christianity in general. She prays for others because she knows it brings them comfort. But Jan does not pray for herself, because she believes in her own ability to cope with life’s problems and in a just God who knows her heart.

Q: What are you hoping readers will gain from this book?

A: We hope all readers will come to appreciate—as we did in conducting our research—the truly remarkable, utterly unanticipated unfolding of Jan Shipps’s life and career. This is a life that should inspire us all. But it should particularly inspire the aspirations of many young LDS women who struggle to strike a working balance between their deeply felt religious and family commitments and the full development of their intrinsic talents, potential to grow, and ability to see and take advantage of life opportunities on an equal par with men. And we hope readers with a scholarly interest in Mormon studies, particularly younger students and scholars whose awareness and interests have developed since the heydays of Jan’s seminal contributions, will become more appreciative of the foundational role Jan played in promoting Mormon studies as an important field of study.

Gary and Gordon Shepherd

Free ebook offer: Knowing Brother Joseph Again: Perceptions and Perspectives May 16 2019

FREE EBOOK FOR NEWSLETTER SUBSCRIBERS

Book description:

This collection of essays by renowned historian Davis Bitton traces how Joseph Smith has appeared from different points of view throughout history. Bitton wrote: "People like Joseph Smith are rich and complex. . . . Different people saw him differently or focused on a different facet of his personality at different times. Inescapably, what they observed or found out about him was refracted through the lens of their own experience. Some of the different, flickering, not always compatible views are the subject of this book.”

“A thoughtful and thought-provoking introductory text for someone wanting an overview of Joseph Smith.” — Improvement Era

STEPS TO DOWNLOAD

**Ebook file must be downloaded onto a laptop or desktop computer. After downloading, you can transfer the file to a tablet or app.**

1. Enter your email address in the form below to sign up for our newsletter and receive a welcome email with instructions (check your junk mail if you do not see it). If you are already a newsletter subscriber, you should have received an email with this free ebook offer and instructions to download.

2. Click the here to open the ebook page on our website. Select which ebook format you wish to download (Kindle, Apple, Nook, or Kobo). The price will show as $19.95 but will change to $0.00 as you complete these steps.

3. Click Add to Cart.

4. Click Checkout.

5. On the Customer Information page, fill out your name and address information. Enter the discount code that you received in the welcome email. The discount code will reduce the price of the book to $0.00.

6. Click Continue to Payment Method. You will not be required to enter payment info. DO NOT ENTER ANY CREDIT CARD INFORMATION.

7. Click Complete Order. You will be emailed a link to download the ebook file along with instructions for transferring the file to an e-reader device or app (check your junk mail if you do not see it).

Note: Once you have downloaded your ebook, it will be on your computer's hard drive, most likely in the "Downloads" folder. Kindle format will end with ".mobi." All other formats will end with ".epub."

FLASH SALE: Select titles up to 75% off! February 14 2019

“Here are riches that you won’t want to miss.” $18.99

|

“Led to a paradigm shift in my understanding of Mormon history.” $23.99

|

“Invaluable as a historical resource.” $26.99

|

Print sale ends Thursday, 2/28/2019

|

$20.95 |

$27.95 |

$32.95 |

Q&A with Melvin C. Johnson for Life and Times of John Pierce Hawley: A Mormon Ulysses of the American West February 08 2019

| Download a free sample preview | Order your copy |

Q: Give us a little information about your background and how you came to become a historian of Mormonism and the American West.

A: I was born in Northern California and grew up in Carlsbad California where I graduated from high school. Renowned historian Will Bagley and I attended the same LDS seminary in Oceanside in the mornings before high school. I pursued degrees at Dixie College in St George Utah and Utah State University in Logan Utah. Then I served twelve years in the military as an airborne infantryman and legal administrator. After being discharged from the military, I attended Stephen F. Austin State University and graduated with a Masters in both history and English. I taught at several universities and colleges and retired from Angelina College in Texas. Halli Wren Johnson, my wife, and I live in Salt Lake City Utah, although we maintain strong connections to eastern Texas. Let me say I loved Dixie College (the only junior college in America, it seemed, that would accept me). I met historian Juanita Brooks there and had no idea who she was, or that the massacre at Mountain Meadows had occurred just thirty-five miles up Highway 18. I had no idea what the massacre at Mountain Meadows even was at the time!

I came to be fascinated by the intersection of Mormonism in the American West at Texas Forestry Museum, Lufkin, Texas. Local forest industries funded my research position in Forest and Mill Town history. During my research, I came across references to the Mormon Millers (sawmills owned and operated by Mormons) of the Texas Hill Country before the American Civil War. I created a Mormon Miller database and began inserting research notes as I came across them in my other pursuits. Eventually, I entwined the Mormon Millers of the Hill Country into my interest in German Texans before the American Civil War and made more intersections. Beginning in 1996, I started researching and out of that came the award-winning Polygamy on the Pedernales: Lyman Wight’s Mormon Villages in Antebellum Texas 1845 to 1858, which won the John Whitmer Historical Association Best Book Award in 2006 funded by the Smith-Pettit Foundation.

During all of that, the life of John Pierce Hawley became a compelling narrative. The son of Sarah and Pierce Hawley, John came of age and the Latter-day Saint Black River Lumber colony in Wisconsin Territory in the early 1840s. Bishop George Miller and Apostle Lyman White directed this lumber mission. The colony's mission was to provide lumber and timber for the construction of the Nauvoo Temple and the Nauvoo House (a large-scale hotel project that never saw completion). Apostle Lyman Wight broke from the Quorum of The Twelve Apostles soon after the death of Joseph Smith Jr. Wight could not submit to Brigham Young's leadership of the Church. Instead, he carried out a mission that was given to him by Joseph Smith Jr. to the Republic of Texas to establish a colony for the Latter Day Saints. John Pierce Hawley help to build the first Mormon temple west of the Mississippi in Zodiac, Texas, in 1849. In it, he was sealed to Sylvia Johnson and was a witness and officiator in the rites and rituals of the Zodiac Temple.

Q: John Pierce Hawley left Wight’s colony, converted to Brigham Young’s Utah church, and became one of the early settlers in southern Utah’s “Dixie” area. What can you tell us about this period of his life?

A: John Pierce Hawley followed Wight for eleven years until he broke with him in 1854 and followed his father, Pierce Hawley, to the Indian nations in what is now Oklahoma. Two years later in the Cherokee Nation, John and Sylvia Hawley (and most of his family and kin) converted to the Utah church led by Brigham Young. That summer and fall the Hawley’s joined the Jacob Croft company and emigrated to Utah Territory. On the trail, they passed the ill-fated Martin and Willie handcart companies. In Utah, the Texans were interviewed and re-baptized, and the Hawleys were sent to Ogden in northern Utah. The following spring, John and his brother George were called, along with many other Texans, to Washington County in southern Utah to begin a mission on the Rio Virgin growing cotton and support a barrier “wall” of colonies that Young built in the Intermountain West to protect the stronghold of Zion.

John and Sylvia Hawley, as well as John’s brother George and his three plural wives, lived in Pine Valley, Utah for thirteen years—from 1857 to 1860. John worked as a road inspector, constable, public and religious school superintendent, and was the presiding elder from 1857 to 1867. However, because John was monogamous, William Snow, brother of Apostle Erastus F. Snow, was installed as the first bishop of Pine Valley. Apostle Snow did not think monogamous priesthood holders should obtain leadership positions in the Church.

Q: Some of John Pierce Hawley’s contemporaries accused him of being involved in the massacre at Mountain Meadows. What does the historical record tell us?

A: After a less than inspiring agricultural year in Washington, the Hawley brothers went to Spanish Fork, Utah, to pick up their wives and be sealed to them in Salt Lake City by Brigham Young. On the return to Dixie, they rode with the doomed Fancher-Baker wagon train that was massacred at Mountain Meadows by the Mormon militia from the Iron County Brigade, commanded by Colonel William Dame. John D. Lee, one of the other militia leaders, later accused John Hawley of being present at the massacre. John’s brothers, George and William, have been identified as being on the Meadows killing fields. John denied any participation in it and even condemned the atrocity in his local congregation. His public condemnation nearly got him killed, as members of his congregation included some of the murderers. A secret meeting resulted in a narrow vote to let him live.

Q: Eventually, John Pierce Hawley left Brigham Young’s church and joined the Reorganized church, led by Joseph Smith III. What can you tell us about the events that led to his conversion?

A: In 1868, several events change John’s life. He received his second endowment under the hands of Apostle Erastus Snow in Salt Lake City and assisted Apostle Snow in giving others their second endowments. John was then sent on a mission to Iowa to convert his RLDS family members to the Utah church. He spent five months there, and as he reported, neither he nor his relatives converted one another. However, John's mission to Iowa planted seeds in him. Over the next year-and-a-half, John struggled with the principles of polygamy, Brigham Young’s Adam-God teachings, the harrowing threat of “blood atonement,” and overbearing priesthood leadership. In November of 1870, both John’s and George Hawley’s families converted to the Reorganized church. They left Salt Lake City on a train to western Iowa and never returned. All the Hawleys in Iowa remained participants in the Reorganized church until their deaths.

Q: In what ways do you think John Hawley’s story is significant within Mormon history?

A: John Pierce Hawley is important because he is a Mormon Ulysses of the American West. His interactions with Mormonism brought him through the interior of the Great American West from the Wisconsin Territory, to the Republic of Texas, to Indian territory, to Utah Territory, and back to Iowa. He crisscrossed the interior of western America five times because of his devotion to Mormonism. He served missions to eastern Texas, along the Missouri and Mississippi rivers, to northern Utah, and western Iowa. He was fascinated with Mormonism and was a fervent disciple of Joseph Smith Jr. His life demonstrated that for him, there was “more than one way to Mormon.” He kept trying until he got it right for himself.

| Download a free sample preview | Order your copy |

Who is Lot Smith? Forgotten Folk Hero of the American West November 06 2018

WHO IS LOT SMITH?

LOT SMITH is a legendary folk hero of the American West whose adventurous life has been all but lost to the annals of time. Lot arrived in the West with the Mormon Batallion during the Mexican-American War. He remained in California during much the Gold Rush, and was later a participant in many significant Utah events, including the Utah-Mormon War, the Walker War, the rescue of the Willie & Martin Handcart Companies, and even joined the Union Army during the US Civil War. Significantly, Lot Smith was one of the early settlers of the Arizona territory and led the United Order efforts in the Little Colorado River settlements. What follows is a brief sketch of Lot's service in the Mormon Batallion and the experiences that shaped him.

Lot was reared by a hard-working Yankee father and a devoutly religious mother. His mother passed when he was fourteen. At the impressionable age of sixteen, Lot joined the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican-American War as one of its youngest members. His father passed before he returned to his family. Consequently, his experiences in the Mormon Battalion shaped his life significantly. The struggles of this heroic infantry march of two-thousand miles across the country embedded within him several valuable characteristics.

Lot Smith came to value the comfort of clothing and shoes in the absence thereof. As the battalion march continued, his clothing and shoes wore out. He had only a ragged shirt and an Indian blanket wrapped around his torso for pants. At the death of one of the soldiers, he gratefully inherited the man’s pants. His feet were shod with rawhide cut from the hocks of an ox. Ever after, he never took shoes for granted. It appears that he may have developed an obsession for them. Soon after his arrival in Utah Territory, he was known to have bought himself a pair of shoes that was outlandishly too large. He said that he wanted to get his money’s worth! Years later, he bought thirty pairs of shoes at a gentile shoe shop. When he saw the astonishment of the shopkeeper, he said, “If these give good service, I’ll be back and buy shoes for the rest of my family!” He frequently carried an extra pair of shoes. In at least two recorded instances, he gave an extra pair of shoes to grateful men who were in desperate need. He knew how feet with no shoes felt—sore, bruised and cut.

Smith developed endurance during the Mormon Battalion march. He carried a shoulder load of paraphernalia, walked as many as twenty-five miles or more each day—sometimes dragging mules through the heavy sand. There was no stopping—and absolutely no pampering. When the going got rough, he had to keep going. He suffered extreme heat and freezing nights on the deserts. Through all of these challenges, he learned to laugh at the hardships and to maintain a happy optimistic view of life. He emerged from the Mormon Battalion as a young man who knew he could do hard things.

It is not known how skilled Smith became with a gun during his battalion march, but during his later years in Arizona, he was known to be an expert marksman who could shoot accurately even from the hip. Every morning he took a practice shot. Navajos and Hopis would come from miles around to challenge him. He gained a reputation of the most feared gunman in Arizona.

Smith faced many life-threatening ordeals throughout the rest of his life. Many different kinds of hardships would test his endurance. He faced them with courage, a trust in God, and an upbeat attitude. His example inspired those who followed him. As a significant and beloved military leader, he knew how to succor those under his command. One who served with him in the military said, “We loved him because he loved us first.”

Lot Smith learned many valuable life lessons on the Mormon Battalion march that served him well. Yes, he rid his table of hot pepper—and he should have done away with something else hot—his temper!

Talana S. Hooper is a native of Arizona’s Gila Valley. She attended both Eastern Arizona College and Arizona State University. She compiled and edited A Century in Central, 1883–1983 and has published numerous family histories. She and her husband Steve have six children and twenty-six grandchildren.

Talana S. Hooper is a native of Arizona’s Gila Valley. She attended both Eastern Arizona College and Arizona State University. She compiled and edited A Century in Central, 1883–1983 and has published numerous family histories. She and her husband Steve have six children and twenty-six grandchildren.

Lot Smith recounts the Mormon frontiersman’s adventures in the Mormon Battalion, the hazardous rescue of the Willie and Martin handcart companies, the Utah War, and the Mormon colonization of the Arizona Territory. True stories of tense relations with the Navajo and Hopi tribes, Mormon flight into Mexico during the US government's anti-polygamy crusades, narrow escapes from bandits and law enforcers, and even Western-style shoot-outs place Lot Smith: Mormon Pioneer and American Frontiersman into both Western Americana literature and Mormon biographical history.

Q&A with Talana S. Hooper for Lot Smith: Mormon Pioneer and American Frontiersman November 01 2018

| Download a free preview | Order your copy |

Q: Give us some background into this book. How did it come together?

A: My grandfather James M. "Jim" Smith was the youngest of Lot Smith's fifty-two children. Since Lot Smith was killed by a renegade Navajo six months before my grandfather's birth, my Grandpa James sought his entire life to learn all he could about the father he never knew. He soon discovered that his father had lived a life which generated myths and legends. He obtained many firsthand accounts which were most often tinged with admiration and love—yet not all were complimentary. Jim Smith's oldest son, my father Omer, recorded the stories and enlisted the help of my mother Carmen to more completely research Lot Smith's history in libraries around the country. When Omer unexpectedly passed, Carmen continued to research, interview, and compile for another thirty years. However, by her mid-nineties, her eyesight had failed enough so that even with her magnifying glass she could no longer see her computer screen well enough to continue. I knew that Lot Smith's life story was too compelling and valuable to be lost. With her blessing and help (while she was still able), I began working to bring the biography together for publication.

Q: For readers who are unfamiliar with Lot Smith, can you give us a basic background of who he was?

A: Lot Smith, a man with a fiery red beard and a temper to match it, experienced firsthand many of the significant events in the early history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. His life was one adventure after another. He joined the Mormon Battalion at the age of sixteen and participated in the California Gold Rush. The life lessons he learned during the Mormon Battalion prepared him for a life of service—many times grueling—for the Church and his fellowmen.

Smith continued his military career. His reputation of fearlessness became widely known as a member of the Minute Men Life Guards—the cavalry that defended the Latter-day Saints in the Rockies from Indians. He was a captain of the Life Guards who rescued the Willie and Martin Handcart Companies. Major Smith served a critical role in defending his fellow Saints from what seemed certain annihilation by the US Army by burning their supplies and wagons in the Utah War. For that act, he was hailed as a hero by the Saints, but indicted for treason in the US courts. After Smith fought in the Walker War, he was appointed as a captain in the US Army to guard telegraph lines and mail routes during the American Civil War. During that service, he and his men endured a harrowing, life-threatening chase after unknown Indians who had stolen two hundred horses. Readers will enjoy several interesting trips with Brigham Young when Smith served as an escort guard. Smith lastly served as Brigadier General in the Black Hawk War and then served a mission in the British Isles.

In 1876 Brigham Young called Smith to lead colonization in the Arizona Territory. Young charged Smith to establish the United Order and to befriend the Indian tribes. Both these directives brought more adventures as they struggled to secure a mere livelihood. Smith served as Arizona's first stake president, and his Sunset United Order provided a way station for others colonizing in New Mexico, Arizona, and Mexico. Smith also helped lead Church colonization in Mexico—another ordeal.

Smith was one of the most feared gunmen in Arizona. He several times drew his gun on men meaning harm but pulled the trigger only once. Besides defending his rights as a stockman, he vowed he would never be arrested for polygamy and narrowly escaped arrest many times. His untimely death came from a shot in the back by a renegade Navajo.

Q: Can you give us a scene from Lot Smith's life that you found particularly interesting?

A: It is difficult to choose just one scene from Lot Smith's life to share. I considered the incident when one of his men was accidentally shot during the Utah War or the rescue of the Martin Handcart Company. I remember the death-defying chase up the Snake River in the Civil War. And then I consider the time when he had a shootout with a man hired to kill him. All are incredible events! And yet, I choose simple episodes Smith shared with his sons.

While Smith lived in Arizona, the federal marshals increased their efforts to arrest any polygamists. Smith had four wives in Arizona, so he was a target. He was always on the alert and evaded arrest many times by riding a fast horse and carrying a fast gun. One time when Lot and his sons were shucking corn in the field, a marshal appeared some distance away. Smith told his boys to shock him up in the corn. When the officer rode up, the boys greeted him cordially. The officer never did figure out how Smith escaped the area!

On another occasion, Smith was traveling with his son Al in a wagon. Lot looked up the road to see a man on horseback and said to Al that it looked like a U.S. Marshal. Since Lot was convinced that no deceit could enter the Kingdom of God, he wanted all his posterity to be honest and truthful at all times—even in the face of danger. So when he saw the marshal, he told his son to stay in the wagon and not to lie, or he'd skin him alive. Lot took his gun and hid behind a bush. The officer approached and asked Al if he were Lot Smith's son. Al replied that he was. Then the officer asked where his father was. Al replied, "Right behind that bush beside you." The officer didn't look; he feared Smith's gun. He merely said, "Well, you tell him that I passed the time of day with him," and said good-bye.

Q: There are a lot of myths and legends that surround Lot Smith. Can you talk about a couple and set the record straight?

A: Several preposterous stories have been attributed to Lot Smith—probably because of his reputation as a rough character with a strong personality, and an expert gunman which caused people to fear him. One widespread myth was that he was involved in the Mountain Meadows Massacre. How could Smith, the hero of the Utah War, be in Wyoming and southern Utah at the same time? Yet the myth persisted, and newspapers printed at his death that he was involved in the massacre.

One of the most oft-repeated myths of Lot Smith was that he branded his wives. It was so widely believed that at the death of his wife Jane in 1912, people still speculated if she had been branded.

The myth followed Smith to Arizona. Children of his last wife, Diantha, were told that their mother had been branded. The real story of Smith "branding his wife" involved his second wife Jane after his first wife Lydia had left. While Lot and two of his friends were branding near his home in Farmington, Jane was preparing dinner for her husband and the guests. Jane needed eggs. She went out and spied some eggs in the manger where she couldn't reach without entering the corral. Jane knew that Lot's stallion chased and bit anyone but Lot, but the stallion seemed to be dozing in the far corner of the corral. She reasoned that she could sneak in unnoticed. However, the stallion was not as drowsy as she has assumed. He jerked up his head, shrieked, and charged Jane. Without dropping his branding iron, Lot jumped and ran between his wife and the stallion. When she ducked to go under the fence, he pushed her through with the branding iron. The men at the branding fire watched as Jane twisted to check her nice skirt that she wore for company. The branding iron had cooled enough that it didn't even scorch it. One of the men laughed and said, "That's one that won't get away from you; she's branded!"

Lot, who loved to entertain and enjoyed a sense of humor, was partially responsible for starting the myth. In church meetings after this incident, he arose to bear his sincere testimony. Along with recounting his blessings, he was heard to say on more than one occasion, "And anything I own, I brand—including my wife!"

Q: What do you hope readers will take away from reading this book?

A: Most of all, I want readers of the Lot Smith biography to enjoy the incredible and fascinating life of Lot Smith. His life was one thrilling adventure after another! Since his life entwined significant events in the early history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I hope that readers get an up-close perspective of some of these events.

I hope readers learn through Lot's experiences that trials and hard circumstances can refine us. When Lot was in the Mormon Battalion, he experienced periods of no food, no water, no shoes, and scanty clothing. His compassion for others in similar situations was born. He was always generous to the poor and could never turn away anyone who was hungry even when food was scarce. It seems he often carried an extra pair of shoes to give away freely.

Lot's strong leadership in the colonization of the destitute Arizona Territory in the United Order was phenomenal. Through hard work and wise leadership, the colonists avoided starvation and established homes. I want readers to more fully realize and understand some of the sacrifices our forefathers made to settle the frontier land for future generations.

| Download a free preview | Order your copy |

Dime Novel Mormons awarded Best Anthology at JWHA September 24 2018

Congratulations to Michael Austin and Ardis E. Parshall for Dime Novel Mormons winning the Best Anthology Award at the 2018 John Whitmer Historical Association meeting!

To celebrate the award, we are offering all titles from the Mormon Image in Literature series for 30% off from Sep 24 through Sep 28. Use discount code DIMENOVEL at check out to get the discount.*

|

$22.95 |

$15.95 |

$12.95 |

*Offer valid for US domestic customers only. Limited to available inventory. Ends 9/28/18.

Q&A Part 2 with the Editors of The Expanded Canon: Perspectives on Mormonism & Sacred Texts September 11 2018

Hardcover $35.95 (ISBN 978-1-58958-637-6)

Part 2: Q&A with Brian D. Birch (Part 1)

Q: When and how did the Mormon Studies program at UVU launch?

A: The UVU Mormon Studies Program began in 2000 with the arrival of Eugene England. Gene received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to explore how Mormon Studies could succeed at a state university. A year-long seminar resulted that included a stellar lineup of consultants and guest scholars. From that point forward, the Religious Studies Program has developed multiple courses complemented by our annual Mormon Studies Conference and Eugene England Lecture—to honor Gene’s tragic and untimely passing in 2001. The program also hosts and facilitates events for independent organizations and publications including the Society for Mormon Philosophy and Theology, the Dialogue Foundation, the Interpreter Foundation, Mormon Scholars in the Humanities, Association for Mormon Letters, and others.

Q: How is the UVU Mormon Studies program distinguished from Mormon Studies programs that have emerged at other campuses?

A: Mormon Studies at UVU is distinguished by the explicitly comparative focus of our work. Given the strengths of our faculty, we have emphasized courses and programming that addresses engagement and dialogue across cultures, faith traditions, and theological perspectives. Permanent course offerings include Mormon Cultural Studies, Mormon Theology and the Christian Tradition, Mormon Anthropology, and Mormon Literature. Our strengths lie in areas other than Mormon history, which is well represented at other institutions—and appropriately so. Given the nature of our institution, our events are focused first and foremost on student learning, but all our events are free and open to the public and we welcome conversation between scholars and nonprofessionals.

Q: How long has the annual UVU Mormon Studies Conference been held, and what have been some of the topics of past conferences?

A: As mentioned above, the Mormon Studies Conference was first convened by Eugene England in 2000, and to date we have convened a total of nineteen conferences. Topics have ranged across a variety of issues including “Islam and Mormonism,” “Mormonism in the Public Mind,” “Mormonism and the Art of Boundary Maintenance,” “Mormonism and the Internet,” etc. We have been fortunate to host superb scholars and to bring them into conversation with each other and the broader public.

Q: Where did the material for the first volume, The Expanded Canon, come from?

A: The material in The Expanded Canon emerged came from our 2013 Mormon Studies Conference that shares the title of the volume. We drew from the work of conference presenters and added select essays to round out the collection. The volume is expressive of our broader approach to bring diverse scholars into conversation and to show a variety of perspectives and methodologies.

Q: What are a few key points about this volume that would be of interest to readers?

A: Few things are more central to Mormon thought than the way the tradition approaches scripture. And many of their most closely held beliefs fly in the face of general Christianity’s conception of scriptural texts. An open or expanded canon of scripture is one example. Grant Underwood explores Joseph Smith’s revelatory capacities and illustrates that Smith consistently edited his revelations and felt that his revisions were done under the same Spirit by which the initial revelation was received. Hence, the revisions may be situated in the canon with the same gravitas that the original text enjoyed. Claudia Bushman directly addresses the lack of female voices in Mormon scripture. She recommends several key documents crafted by women in the spirit of revelation. Ultimately, she suggests several candidates for inclusion. As the Mormon canon expands it should include female voices. From a non-Mormon perspective, Ann Taves does not embrace a historical explanation of the Book of Mormon or the gold plates. However, she does not deny Joseph Smith as a religious genius and compelling creator of a dynamic mythos. In her chapter she uses Mormon scripture to suggest a way that the golden plates exist, are not historical, but still maintain divine connectivity. David Holland examines the boundaries and intricacies of the Mormon canon. Historically, what are the patterns and intricacies of the expanding canon and what is the inherent logic behind the related processes? Additionally, authors treat the status of the Pearl of Great Price, the historical milieu of the publication of the Book of Mormon, and the place of The Family: A Proclamation to the World. These are just a few of the important issues addressed in this volume.

Q: What is your thought process behind curating these volumes in terms of representation from both LDS and non-LDS scholars, gender, race, academic disciplines, etc?

A: Mormon Studies programing at UVU has always been centered on strong scholarship while also extending our reach to marginalized voices. To date, we have invited guests that span a broad spectrum of Mormon thought and practice. From Orthodox Judaism to Secular Humanists; from LGBTQ to opponents to same-sex marriage; from Feminists to staunch advocates of male hierarchies, all have had a voice in the UVU Mormon Studies Program. Each course, conference, and publication treating these dynamic dialogues in Mormonism are conducted in civility and the scholarly anchors of the academy. Given our disciplinary grounding, our work has expanded the conversation and opened a wide variety of ongoing cooperation between schools of thought that intersect with Mormon thought.

Q: What can readers expect to see coming from the UVU Comparative Mormon Studies series?

A: Our 2019 conference will be centered on the experience of women in and around the Mormon traditions. We have witnessed tremendous scholarship of late in this area and are anxious to assemble key authors and advocates. Other areas we plan to explore include comparative studies in Mormonism and Asian religions, theological approaches to religious diversity, and questions of Mormon identity.

Download a free sample of The Expanded Canon

Listen to an interview with the editors

Upcoming events for The Expanded Canon:

Tue Sep 18 at 7pm | Writ & Vision (Provo) | RSVP on Facebook

Wed Sep 19 at 5:30 pm | Benchmark Books (SLC) | RSVP on Facebook

Q&A Part 1 with the Editors of The Expanded Canon: Perspectives on Mormonism & Sacred Texts August 29 2018

Hardcover $35.95 (ISBN 978-1-58958-637-6)

Part 1: Q&A with Blair G. Van Dyke (Part 2)

Q: How is the Mormon Studies program at Utah Valley University distinguished from Mormon Studies programs that have emerged at other universities?

A: The Mormon Studies program at UVU is distinguished by the comparative components of the work we do. At UVU we cast a broad net across the academy knowing that there are relevant points of exploration at the intersections of Mormonism and the arts, Mormonism and the sciences, Mormonism and literature, Mormonism and economics, Mormonism and feminism, Mormonism and world religions, and so forth. Additionally, the program is distinguished from other Mormon Studies by the academic events that we host. UVU initiated and maintains the most vibrant tradition of creating and hosting relevant and engaging conferences, symposia, and intra-campus events than any other program in the country. Further, a university-wide initiative is in place to engage the community in the work of the academy. Hence, the events held on campus are focused first and foremost for students but inviting the community to enjoy our work is very important. This facilitates understanding and builds bridges between scholars of Mormon Studies and Mormons and non-Mormons outside academic orbits.

Q: Where did the material for The Expanded Canon come from?

A: The material that constitutes volume one of the UVU Comparative Mormon Studies Series came from an annual Mormon Studies Conference that shares the title of the volume. We drew from the work of some of the scholars that presented at that conference to give their work and ours a broader audience. Generally, the contributors to the volume are not household names or prominent authors that regularly publish in the common commercial publishing houses directed at Mormon readership. As such, this volume introduces that audience to prominent personalities in the field of Mormon Studies. It is not uncommon for scholars in this field of study to look for venues where their work can reach a broader readership. This jointly published volume accomplishes that desire in a thoughtful way.

Q: What are a few key points about this volume that would be of interest to readers?

A: Few things are more central to Mormon thought than the way the tradition approaches scripture. And many of their most closely held beliefs fly in the face of general Christianity’s conception of scriptural texts. An open or expanded canon of scripture is one example. Grant Underwood explores Joseph Smith’s revelatory capacities and illustrates that Smith consistently edited his revelations and felt that his revisions were done under the same Spirit by which the initial revelation was received. Hence, the revisions may be situated in the canon with the same gravitas that the original text enjoyed. Claudia Bushman directly addresses the lack of female voices in Mormon scripture. She recommends several key documents crafted by women in the spirit of revelation. Ultimately, she suggests several candidates for inclusion. As the Mormon canon expands it should include female voices. From a non-Mormon perspective, Ann Taves does not embrace a historical explanation of the Book of Mormon or the gold plates. However, she does not deny Joseph Smith as a religious genius and compelling creator of a dynamic mythos. In her chapter she uses Mormon scripture to suggest a way that the golden plates exist, are not historical, but still maintain divine connectivity. David Holland examines the boundaries and intricacies of the Mormon canon. Historically, what are the patterns and intricacies of the expanding canon and what is the inherent logic behind the related processes? Additionally, authors treat the status of the Pearl of Great Price, the historical milieu of the publication of the Book of Mormon, and the place of The Family A Proclamation to the World. These are just a few of the important issues addressed in this volume.