News

FLASH SALE: Award-winning Latter-day Saint books — 30% off retail prices! September 23 2020

We are proud of our authors and books! Expand your collection of biographies and narrative histories, anthologies and personal essays, and scripture scholarship with these award-winning titles below. Now 30% off through the end of September.

Sale ends Wednesday, 9/30/2020*

|

2020 Best Biography, JWHA $24.95 |

2018 Best Anthology, JWHA $22.95 |

2017 Best International History, MHA $39.95 |

|

2016 Best Literary Criticism, AML $18.95 |

2016 Best Religious Non-fiction, AML $20.95 |

2016 Best Biography, JWHA $39.95 |

|

2015 Best Religious Non-fiction, AML $34.95 |

2015 Best Book Award, MHA $32.95 |

2015 Best International History, MHA $24.95 |

|

2014 Best Religious Non-fiction, AML $20.95 |

2014 Best International Book, MHA $34.95 |

2013 Best International History, MHA $29.95 |

|

2012 Best Biography, MHA $31.95 |

2012 Best Criticism Award, AML $34.95 |

2011 Best Book Award, MHA & JWHA $34.95 |

|

2007 Best Book Award, JWHA $31.95 |

2003 Best Biography, MHA $32.95 |

1988 Best Book Award, MHA $31.95 |

*For international print orders, email order@koffordbooks.com. Subject to available supply.

PIONEER DAY FLASH SALE: Up to 70% off Select History Titles July 23 2019

|

“A riveting compilation for any reader looking to discover this monumental and defining experience in Mormon history through the accounts of the common people who lived it.” — BYU Studies |

Print 30% off Ebook 70% off |

|

“Will be a standard work on the Nauvoo Temple among the Mountain Saints for many years to come.” —Dialogue Journal |

Print 30% off Ebook 70% off |

|

“This is a fascinating book worthy of a truly fascinating nineteenth-century frontiersman.” |

Print 30% off Ebook 70% off |

|

Jedediah Morgan Grant’s voice rises powerfully in these pages, startling in its urgency in summoning his people to sacrifice and moving in its tenderness as he communicated to his family. |

Print 30% off Ebook 70% off |

|

Embry offers a new perspective on the Mormon practice of polygamy that enables readers to gain better understanding of Mormonism historically. |

Print 30% off Ebook 70% off |

|

“A marvelous record of an LDS everyman meandering through the Mormon West. . . . Fascinating and superbly researched.” |

Print 30% off Ebook 70% off |

|

“Bleak’s annals are a lasting tribute to the early settlers of Southern Utah and will yet influence many thousand more in our day. The wonderful work in this volume makes that possible.” —Elder Steven E. Snow, LDS Church Historian and Recorder |

Print 30% off

|

Who is Lot Smith? Forgotten Folk Hero of the American West November 06 2018

WHO IS LOT SMITH?

LOT SMITH is a legendary folk hero of the American West whose adventurous life has been all but lost to the annals of time. Lot arrived in the West with the Mormon Batallion during the Mexican-American War. He remained in California during much the Gold Rush, and was later a participant in many significant Utah events, including the Utah-Mormon War, the Walker War, the rescue of the Willie & Martin Handcart Companies, and even joined the Union Army during the US Civil War. Significantly, Lot Smith was one of the early settlers of the Arizona territory and led the United Order efforts in the Little Colorado River settlements. What follows is a brief sketch of Lot's service in the Mormon Batallion and the experiences that shaped him.

Lot was reared by a hard-working Yankee father and a devoutly religious mother. His mother passed when he was fourteen. At the impressionable age of sixteen, Lot joined the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican-American War as one of its youngest members. His father passed before he returned to his family. Consequently, his experiences in the Mormon Battalion shaped his life significantly. The struggles of this heroic infantry march of two-thousand miles across the country embedded within him several valuable characteristics.

Lot Smith came to value the comfort of clothing and shoes in the absence thereof. As the battalion march continued, his clothing and shoes wore out. He had only a ragged shirt and an Indian blanket wrapped around his torso for pants. At the death of one of the soldiers, he gratefully inherited the man’s pants. His feet were shod with rawhide cut from the hocks of an ox. Ever after, he never took shoes for granted. It appears that he may have developed an obsession for them. Soon after his arrival in Utah Territory, he was known to have bought himself a pair of shoes that was outlandishly too large. He said that he wanted to get his money’s worth! Years later, he bought thirty pairs of shoes at a gentile shoe shop. When he saw the astonishment of the shopkeeper, he said, “If these give good service, I’ll be back and buy shoes for the rest of my family!” He frequently carried an extra pair of shoes. In at least two recorded instances, he gave an extra pair of shoes to grateful men who were in desperate need. He knew how feet with no shoes felt—sore, bruised and cut.

Smith developed endurance during the Mormon Battalion march. He carried a shoulder load of paraphernalia, walked as many as twenty-five miles or more each day—sometimes dragging mules through the heavy sand. There was no stopping—and absolutely no pampering. When the going got rough, he had to keep going. He suffered extreme heat and freezing nights on the deserts. Through all of these challenges, he learned to laugh at the hardships and to maintain a happy optimistic view of life. He emerged from the Mormon Battalion as a young man who knew he could do hard things.

It is not known how skilled Smith became with a gun during his battalion march, but during his later years in Arizona, he was known to be an expert marksman who could shoot accurately even from the hip. Every morning he took a practice shot. Navajos and Hopis would come from miles around to challenge him. He gained a reputation of the most feared gunman in Arizona.

Smith faced many life-threatening ordeals throughout the rest of his life. Many different kinds of hardships would test his endurance. He faced them with courage, a trust in God, and an upbeat attitude. His example inspired those who followed him. As a significant and beloved military leader, he knew how to succor those under his command. One who served with him in the military said, “We loved him because he loved us first.”

Lot Smith learned many valuable life lessons on the Mormon Battalion march that served him well. Yes, he rid his table of hot pepper—and he should have done away with something else hot—his temper!

Talana S. Hooper is a native of Arizona’s Gila Valley. She attended both Eastern Arizona College and Arizona State University. She compiled and edited A Century in Central, 1883–1983 and has published numerous family histories. She and her husband Steve have six children and twenty-six grandchildren.

Talana S. Hooper is a native of Arizona’s Gila Valley. She attended both Eastern Arizona College and Arizona State University. She compiled and edited A Century in Central, 1883–1983 and has published numerous family histories. She and her husband Steve have six children and twenty-six grandchildren.

Lot Smith recounts the Mormon frontiersman’s adventures in the Mormon Battalion, the hazardous rescue of the Willie and Martin handcart companies, the Utah War, and the Mormon colonization of the Arizona Territory. True stories of tense relations with the Navajo and Hopi tribes, Mormon flight into Mexico during the US government's anti-polygamy crusades, narrow escapes from bandits and law enforcers, and even Western-style shoot-outs place Lot Smith: Mormon Pioneer and American Frontiersman into both Western Americana literature and Mormon biographical history.

Q&A with Talana S. Hooper for Lot Smith: Mormon Pioneer and American Frontiersman November 01 2018

| Download a free preview | Order your copy |

Q: Give us some background into this book. How did it come together?

A: My grandfather James M. "Jim" Smith was the youngest of Lot Smith's fifty-two children. Since Lot Smith was killed by a renegade Navajo six months before my grandfather's birth, my Grandpa James sought his entire life to learn all he could about the father he never knew. He soon discovered that his father had lived a life which generated myths and legends. He obtained many firsthand accounts which were most often tinged with admiration and love—yet not all were complimentary. Jim Smith's oldest son, my father Omer, recorded the stories and enlisted the help of my mother Carmen to more completely research Lot Smith's history in libraries around the country. When Omer unexpectedly passed, Carmen continued to research, interview, and compile for another thirty years. However, by her mid-nineties, her eyesight had failed enough so that even with her magnifying glass she could no longer see her computer screen well enough to continue. I knew that Lot Smith's life story was too compelling and valuable to be lost. With her blessing and help (while she was still able), I began working to bring the biography together for publication.

Q: For readers who are unfamiliar with Lot Smith, can you give us a basic background of who he was?

A: Lot Smith, a man with a fiery red beard and a temper to match it, experienced firsthand many of the significant events in the early history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. His life was one adventure after another. He joined the Mormon Battalion at the age of sixteen and participated in the California Gold Rush. The life lessons he learned during the Mormon Battalion prepared him for a life of service—many times grueling—for the Church and his fellowmen.

Smith continued his military career. His reputation of fearlessness became widely known as a member of the Minute Men Life Guards—the cavalry that defended the Latter-day Saints in the Rockies from Indians. He was a captain of the Life Guards who rescued the Willie and Martin Handcart Companies. Major Smith served a critical role in defending his fellow Saints from what seemed certain annihilation by the US Army by burning their supplies and wagons in the Utah War. For that act, he was hailed as a hero by the Saints, but indicted for treason in the US courts. After Smith fought in the Walker War, he was appointed as a captain in the US Army to guard telegraph lines and mail routes during the American Civil War. During that service, he and his men endured a harrowing, life-threatening chase after unknown Indians who had stolen two hundred horses. Readers will enjoy several interesting trips with Brigham Young when Smith served as an escort guard. Smith lastly served as Brigadier General in the Black Hawk War and then served a mission in the British Isles.

In 1876 Brigham Young called Smith to lead colonization in the Arizona Territory. Young charged Smith to establish the United Order and to befriend the Indian tribes. Both these directives brought more adventures as they struggled to secure a mere livelihood. Smith served as Arizona's first stake president, and his Sunset United Order provided a way station for others colonizing in New Mexico, Arizona, and Mexico. Smith also helped lead Church colonization in Mexico—another ordeal.

Smith was one of the most feared gunmen in Arizona. He several times drew his gun on men meaning harm but pulled the trigger only once. Besides defending his rights as a stockman, he vowed he would never be arrested for polygamy and narrowly escaped arrest many times. His untimely death came from a shot in the back by a renegade Navajo.

Q: Can you give us a scene from Lot Smith's life that you found particularly interesting?

A: It is difficult to choose just one scene from Lot Smith's life to share. I considered the incident when one of his men was accidentally shot during the Utah War or the rescue of the Martin Handcart Company. I remember the death-defying chase up the Snake River in the Civil War. And then I consider the time when he had a shootout with a man hired to kill him. All are incredible events! And yet, I choose simple episodes Smith shared with his sons.

While Smith lived in Arizona, the federal marshals increased their efforts to arrest any polygamists. Smith had four wives in Arizona, so he was a target. He was always on the alert and evaded arrest many times by riding a fast horse and carrying a fast gun. One time when Lot and his sons were shucking corn in the field, a marshal appeared some distance away. Smith told his boys to shock him up in the corn. When the officer rode up, the boys greeted him cordially. The officer never did figure out how Smith escaped the area!

On another occasion, Smith was traveling with his son Al in a wagon. Lot looked up the road to see a man on horseback and said to Al that it looked like a U.S. Marshal. Since Lot was convinced that no deceit could enter the Kingdom of God, he wanted all his posterity to be honest and truthful at all times—even in the face of danger. So when he saw the marshal, he told his son to stay in the wagon and not to lie, or he'd skin him alive. Lot took his gun and hid behind a bush. The officer approached and asked Al if he were Lot Smith's son. Al replied that he was. Then the officer asked where his father was. Al replied, "Right behind that bush beside you." The officer didn't look; he feared Smith's gun. He merely said, "Well, you tell him that I passed the time of day with him," and said good-bye.

Q: There are a lot of myths and legends that surround Lot Smith. Can you talk about a couple and set the record straight?

A: Several preposterous stories have been attributed to Lot Smith—probably because of his reputation as a rough character with a strong personality, and an expert gunman which caused people to fear him. One widespread myth was that he was involved in the Mountain Meadows Massacre. How could Smith, the hero of the Utah War, be in Wyoming and southern Utah at the same time? Yet the myth persisted, and newspapers printed at his death that he was involved in the massacre.

One of the most oft-repeated myths of Lot Smith was that he branded his wives. It was so widely believed that at the death of his wife Jane in 1912, people still speculated if she had been branded.

The myth followed Smith to Arizona. Children of his last wife, Diantha, were told that their mother had been branded. The real story of Smith "branding his wife" involved his second wife Jane after his first wife Lydia had left. While Lot and two of his friends were branding near his home in Farmington, Jane was preparing dinner for her husband and the guests. Jane needed eggs. She went out and spied some eggs in the manger where she couldn't reach without entering the corral. Jane knew that Lot's stallion chased and bit anyone but Lot, but the stallion seemed to be dozing in the far corner of the corral. She reasoned that she could sneak in unnoticed. However, the stallion was not as drowsy as she has assumed. He jerked up his head, shrieked, and charged Jane. Without dropping his branding iron, Lot jumped and ran between his wife and the stallion. When she ducked to go under the fence, he pushed her through with the branding iron. The men at the branding fire watched as Jane twisted to check her nice skirt that she wore for company. The branding iron had cooled enough that it didn't even scorch it. One of the men laughed and said, "That's one that won't get away from you; she's branded!"

Lot, who loved to entertain and enjoyed a sense of humor, was partially responsible for starting the myth. In church meetings after this incident, he arose to bear his sincere testimony. Along with recounting his blessings, he was heard to say on more than one occasion, "And anything I own, I brand—including my wife!"

Q: What do you hope readers will take away from reading this book?

A: Most of all, I want readers of the Lot Smith biography to enjoy the incredible and fascinating life of Lot Smith. His life was one thrilling adventure after another! Since his life entwined significant events in the early history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I hope that readers get an up-close perspective of some of these events.

I hope readers learn through Lot's experiences that trials and hard circumstances can refine us. When Lot was in the Mormon Battalion, he experienced periods of no food, no water, no shoes, and scanty clothing. His compassion for others in similar situations was born. He was always generous to the poor and could never turn away anyone who was hungry even when food was scarce. It seems he often carried an extra pair of shoes to give away freely.

Lot's strong leadership in the colonization of the destitute Arizona Territory in the United Order was phenomenal. Through hard work and wise leadership, the colonists avoided starvation and established homes. I want readers to more fully realize and understand some of the sacrifices our forefathers made to settle the frontier land for future generations.

| Download a free preview | Order your copy |

Newell G. Bringhurst Speaking Events April 13 2018

| Date & Time | Location |

| Tue April 24 at 5:30 PM | Benchmark Books, SLC |

| Thur April 26 at 7:00 PM | Writ & Vision, Provo |

| Fri April 27 at 5:00 PM | Main Street Books, Cedar City |

| Sat April 28 at 4:00 PM | Home of Doug Bowen, St. George |

NOW AVAILABLE

“An excellent treatment of an important part of American religious life. Bringhurst succeeds in showing the Mormons as a microcosm of the American population.” — The American Historical Review

“In many regards Bringhurst established the terms on which subsequent scholars would engage race and Mormonism” — W. Paul Reeve, author of Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness

Sign up for our newsletter to stay informed

about future events and book releases

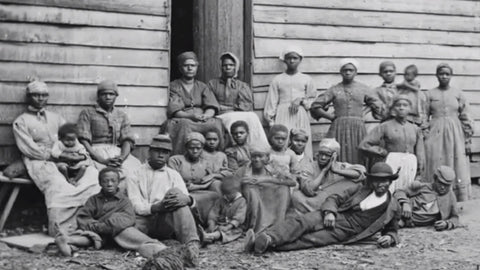

Five Times Mormons Changed Their Position on Slavery March 28 2018

Mormonism and Black Slavery:

Changing Attitudes and Related Practices, 1830–1865

By Newell G. Bringhurst

Mormon attitudes and practices relative to black slavery shifted over the course of the first thirty-five years of the Latter-day Saint movement, evolving through five distinct phases.

Phase 1 – Opposition to Slavery in the Book of Mormon

Initially Joseph Smith expressed strong opposition to slavery through the pages of the Book of Mormon. While not specifically referring to black people, Mormonism’s foundational work asserted that “it was against [Nephite] law” to enslave those less favored than themselves, namely the dark Lamanites (Alma 27:9; Mosiah 2:13). In fact, the idolatrous Lamanites were the ones who practiced slavery, making repeated efforts to enslave the light-skinned, chosen Nephites. Lamanite slaveholding was cited as proof of this people’s “ferocious and wicked nature” (Alma 50:22). Nephite resistance to the Lamanites was described as a struggle for freedom from bondage and slavery.

Phase 2 –Detachment towards Slavery in Ohio and Missouri

Mormon attitudes toward slavery entered a second phase of deliberate detachment following the formal organization of the Church in 1830. Through the pages of the Church’s official newspaper, the Evening and Morning Star, Joseph Smith and others avoided discussion of this increasingly controversial topic. No mention was made of Book of Mormon verses condemning slavery. A major reason for such deliberate detachment was the establishment of Mormonism’s Zion in Missouri, a slave state. Church officials sought to disassociate themselves from the fledgling Abolitionist movement.

Despite this, the Church found itself compelled to speak out on the issue on two important occasions. The first involved Joseph Smith’s “Revelation and Prophecy on War” brought forth on 25 December 1832 and ultimately canonized as Section 87 in the Doctrine and Covenants. In this apocalyptic document, Smith prophesized that “wars…will shortly come to pass, beginning at the rebellion of South Carolina [and]…poured out on all nations” (D&C 87:1–2). It further declared that the “slaves will rise up against their masters, who shall be marshalled and disciplined for war” (D&C 87:4). Given its explosive implications, this revelation was not disclosed to the general Church membership until two decades later.

By contrast, a second Mormon statement, “Free People of Color” written by W. W. Phelps and published in the July 1833 issue of the Evening and Morning Star, received immediate exposure resulting in dire consequences. Prompting Phelps’s statement was a dramatic four-fold increase in the number of Mormons settling in Jackson County. The article’s stated purpose was “to prevent any misunderstanding . . . respecting free people of color, who may think of coming to . . . Missouri as members of the Church.”[1] However, it had the opposite effect, angering local non-Mormons who expelled the Latter-day Saints from Jackson County.

Phase 3 – Pro-slavery Sympathies in Missouri

By the mid 1830s, Church attitudes toward slavery shifted yet a third time, Church spokesmen affirming support for slavery. In August 1835, the Church issued an official declaration stating that it was not “right to interfere with bond-servants, nor baptize them contrary to the will and wish of their masters” nor cause “them to be dissatisfied with their situations in this life.” Ultimately this statement was incorporated into the Doctrine and Covenants as Section 134. Eight months later, in April 1836, Joseph Smith reaffirmed Mormon pro-slavery sympathies through a lengthy discourse published in the official Latter-day Saints Messenger and Advocate. Smith raised the specter of “racial miscegenation and possible race war” if abolitionism prevailed.[2] He further stated that the people of the North have no “more right to say that the South shall not hold slaves, than the South have to say the North shall.”[3] He referenced the Old Testament, specifically the “decree of Jehovah” that blacks were cursed with servitude.[4] Other church spokesmen echoed Smith’s sentiments, in particular Oliver Cowdery and Warren Parrish. This Mormon shift reflected an increased Mormon presence in the slave state of Missouri during the late 1830s, along with a desire to carry the Mormon message to potential converts in the slaveholding South. But most importantly, it represented strong Mormon reaction against the establishment of a chapter of the American Anti-slavery society in the Mormon community of Kirtland Ohio.

Phase 4 – Anti-slavery Position in Nauvoo

By the early 1840s Smith and his followers shifted their position yet a fourth time, assuming a strong anti-slavery position, most evident during the Mormon leader’s 1844 campaign for U.S. president. In his “Views on the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States” Smith advocated the abolition of slavery through gradual emancipation and colonization of the freed blacks abroad.[5] He called for the “break down [of] slavery” and removal of “the shackles from the poor black man” through a program of compensated emancipation financed through the sale of public lands.[6] Smith predicted that his proposal could eliminate slavery by 1850. Motivating this changing position were two major factors: one was the Mormon’s forced expulsion from the slave state of Missouri in 1838-39. The second involved demographics, namely the fact that the majority of church members hailed from non-slaveholding regions north of the Mason-Dixon line and from Great Britain. By contrast, a relatively limited number of new converts were drawn from the slaveholding South.

Phase 5 – Pro-slavery Position in Utah Territory

Mormon attitudes and related practices relative to slavery shifted yet a fifth and final time following the death of Joseph Smith in 1844 with the emergence of Brigham Young as the principal leader of the Latter-day Saints who migrated west. Young’s evolving position represented “a bundle of contradictions.”[7] Initially, he advocated a “free soil”[8] stance in a June, 1851, sermon, rhetorically stating, “shall we lay a foundation for Negro slavery? No, God forbid!”[9] Six months later in the wake of his appointment as Utah Territorial Governor, Young retreated from this position. Despite his assertion that “my own feelings are that no property can or should exist in slaves,” Young called on the territorial legislature adopt a form of benevolent indentured servitude to regulate Utah’s small but visible black population.[10] Two weeks later, addressing that same body, he proclaimed himself “a firm believer in slavery,”[11] urging legalization of the Peculiar Institution.[12] On February 4, 1952, the Utah Territorial Legislature passed “An Act in Relation to Service” which Young signed into law, making Utah the only Western territory to allow black slavery. Justifying his action, Young delivered a lengthy discourse in which he promoted a direct link between black slavery and black priesthood denial—the latter practice which he announced publicly for the first time. He further asserted that the two proscriptions were both intertwined and divinely sanctioned.

Four factors prompted Young to promote “An Act in Relation to Service.” First, the measure represented a response to the presence of sixty to seventy black slaves in the territory belonging to twelve Mormon slave owners. Among the most prominent were Apostle Charles C. Rich, William H. Hooper (an important Mormon merchant who served as Utah’s Territorial delegate to Congress), and Abraham O. Smoot, Salt Lake City’s first mayor. Second, Young hoped to secure southern support for Utah statehood. Young noted that there were “many [brethren] in the South with a great amount [invested] in slaves” who might migrate to the Great Basin if their slavery property were protected by law.[13]

Of crucial importance in motivating the Mormon leader was a third factor: his strong, unyielding belief that blacks were inherently inferior to whites in all respects and thus naturally fit for involuntary servitude. He accepted, uncritically, the traditional biblical genealogy that present-day Africans came through the so-called accursed lineage of Canaan and Ham back to Cain, thereby providing divine sanction to their servile condition. Further legitimizing black inferiority was the denial of priesthood ordination to black males, which Young affirmed as “a true eternal [principle] the Lord Almighty has ordained.” He stated: “If there never was a prophet or apostle of Jesus Christ spoke it before, I tell you, this people that are commonly called negroes are the children of old Cain, I know they are, I know that they cannot bear rule in the priesthood.”[14]

A fourth, seemingly counterintuitive factor activated Young: his desire to discourage slaveholding in the territory. A careful reading of the statute’s provisions indicates that it consisted primarily of rules to control and restrict slaveholders, and only, incidentally, proscriptions on black slaves themselves. For example, the act required Utah slaveholders to prove that servile blacks had entered the territory “of their own free will and choice.”[15] It also stated that slaveholders could not sell their slaves or remove them from the territory without the so-called servants explicit consent. In general, “An Act in Relation to Service” contrasted sharply with Southern slaveholding statutes in that it was more akin to the practice of indentured servitude. Later that same year, Young reflected on the act’s impact, claiming that it had “nearly freed the territory of the colored population.”[16] Ultimately, Utah Territorial slavery was completely outlawed through a federal statute enacted in 1862, affecting not just the Mormon-dominated region but all other federal territories as well.

Conclusion

The LDS Church’s ever shifting encounter with the institution of black slavery during the thirty-five years from 1830 to 1865 represents a complex, often contradictory odyssey. This perplexing journey profoundly affected Mormonism’s relationship with black people in general. While the number of blacks that Latter-day Saints actually held in bondage was miniscule, the fact that Brigham Young sanctioned the practice of black slavery in conjunction with his imposition of black priesthood and temple denial underscores slavery’s seminal impact on the now-defunct proscription on black people—such practice viewed as Church doctrine for over one hundred and twenty-five years.

Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People Within Mormonism, 2nd ed.

Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People Within Mormonism, 2nd ed.

By Newell G. Bringhurst

Available April 10, 2018

Pre-order today

[1] Evening and Morning Star, July 1833.

[2] Joseph Smith, “Letter to the Editor,” Latter Day Saints Messenger and Advocate, April 1836

[3] Smith, “Letter to the Editor.”

[4] Smith, “Letter to the Editor.”

[6] Smith, “Views on the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States.”

[12] Peculiar Institution is another term for Black Slavery.

[13] “Speech [sic] by Gov. Young in Counsel on a Bill relating to the Affican [sic] Slavery.”

[14] Brigham Young, Discourse, February 5, 1852, Bx 1 Fd. 17, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Historical Department.

[15] “AN ACT in relation to Service,” Acts, Resolutions and Memorials of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Utah (Salt Lake City, 1855), 160–62.

[16] Brigham Young, “Message to the Joint Session of the Legislature,” 13 December 1852, Brigham Young papers.