News

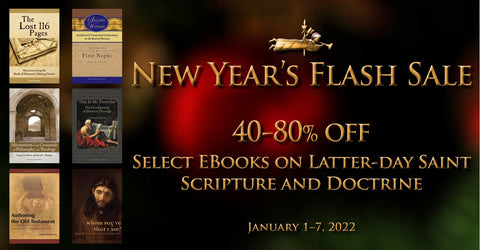

New Year's Ebook Flash Sale December 27 2021

As we welcome 2022, we are pleased to offer discounted prices on select ebooks on scripture and doctrine. This sale runs from January 1–7 and is available for Kindle and Apple ebooks.

Sale ends Friday, Jan 7.

|

|

Scripture |

|

|

$27.99 |

$29.99 |

$29.99 |

|

$29.99 |

$29.99 |

$29.99 |

|

$29.99 |

$22.99 |

|

|

$18.99 |

$25.99 |

$27.99 |

|

$17.99 |

$20.99 |

$17.99 |

|

$22.99 |

$9.99 |

|

|

$22.99 |

$23.99 |

|

|

|

Doctrine |

|

|

$16.99 |

$16.99 |

|

|

$23.99 |

$23.99 |

|

|

$22.99 |

$9.99 |

|

|

$16.99 |

$22.99 |

|

|

$18.99 |

$22.99 |

Q&A with Joseph M. Spencer, author of The Anatomy of Book of Mormon Theology November 14 2021

Joseph M. Spencer, November 2021

New Year's Ebook Flash Sale December 29 2020

As we welcome 2021, we are pleased to offer discounted prices on select ebooks on scripture, doctrine, and community. This sale runs from January 1–4 and is available for both Kindle and Apple ebooks.

Sale ends Monday, Jan 4.

Doctrine| Scripture | ||

|

$17.99 |

$27.99 |

$22.99 |

|

$18.99 |

$22.99 |

$23.99 |

| Doctrine | ||

|

$30.99 |

$17.99 |

$9.99 |

|

$26.99 |

$16.99 |

$18.99 |

| Community | ||

|

$18.99 |

$14.99 |

$18.99 |

|

$23.99 |

$18.99 |

$9.99 |

2020 Holiday Gift Guide November 11 2020

This holiday season, we are focusing on themes of scripture, doctrine, and community. Below is a holiday buyer's guide highlighting a few of our most popular titles.

To see our Black Friday Sales, click here.

Scripture

|

With the Doctrine & Covenants being the 2021 focus for Come Follow Me, Mark Lyman Staker's award-winning history, Hearken, O Ye People, is the perfect gift for those interested in the historical context behind the revelations Joseph Smith received in Ohio. A perfect compliment to your Come Follow Me study. |

|

One of our most popular titles! The Lost 116 Pages does more than tell the history behind the missing manuscript pages from the early translation of the Book of Mormon, it also uses the best scholarly tools available to analyze internal and external evidence and piece together what may have been in the lost pages. The result tells us as much about the existing Book of Mormon as it does the lost pages. Perfect for those who enjoy taking deep dives into scripture and history! |

|

Award-winning Book of Mormon scholar, Brant Gardner, looks at Joseph Smith's translation process of the Book of Mormon. The Gift and Power analyzes not only the mechanics of the translation process, but also asks how closely Joseph Smith followed the original Nephite writings. This is the perfect book for those interested in how the Book of Mormon was produced, affirming that it is an ancient text miraculously brought forth by the gift and power of God. |

|

The Second Witness series by Brant Gardner is lauded as the most comprehensive Book of Mormon commentary in existence. Brant uses his extensive knoweledge and backgroud into Mesoamerican anthropology and intertextual studies to bring the Book of Mormon to life for modern readers. Second Witness can be purchased as a set or individual volumes. A must have for the serious student of the Book of Mormon. |

|

Authoring the Old Testament launched our Contemporary Studies in Scripture series, which utilizes the best tools of biblical scholarship to speak to a Latter-day Saint audience. Authoring the Old Testament introduces Latter-day Saint readers to the documentary hypothesis and offers a faith-affirming approach to Hebrew Bible authorship in line with contemporary scholarship. |

|

Continuing with the Contemporary Studies in Scripture series, The Vision of All by Joseph Spencer has been a consistent top seller. The Vision of All analyzis Nephi's use of Isaiah writings in the Book of Mormon, offering a reader-friendly explanation of these challenging prophetic passages. Perfect for readers who want to understand more about Isaiah's writings as well as Nephi's inclusion of them in the Book of Mormon. |

Doctrine

|

Blake T. Ostler's Exploring Mormon Thought series is the first series ever published by Greg Kofford Books and is still considerd the standard by which faith-affirming Latter-day Saint philosophy is measured. For readers interested in deep philosophical questions regarding the nature of God, human agency, mankind's divine potential, and the problem of evil and suffering in the world, this is the series to get! |

|

Perhaps of all questions asked about Latter-day Saint doctrine and history, the historic practice of plural marriage is the most divisive. Brian C. Hales's Joseph Smith's Polygamy series is the most in-depth source of research avaiable on the origins of polygamy. Joseph Smith's Polygamy: Toward a Better Understanding, condenses this research into a reader-friendly format. This is essential reading for those who want to better understand the topic of plural marriage while affirming their belief in Joseph Smith's prophetic calling. |

|

In For Zion, Joseph M. Spencer, assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University, picks up where Hugh Nibley's Approaching Zion left off. In this approachable and inspiring text, Joseph expands the concept of consecration beyond the material and economic into one of transformation of the human heart. An excellent book for those who enjoy Latter-day Saint teachings about the promise of Zion and the writings of High Nibley. |

|

Considered a classic examination of Latter-day Saint doctrine by many, This is My Doctrine by Charles R. Harrell looks closely at the development of key Latter-day Saint teachings and the ongoing conversation between ancient belief and modern-day revelation. This book challenges its readers to see God's hand at work in the evolving nature of doctrine. The perfect book for those who enjoy studying Latter-day Saint doctrine and belief. |

Community

| One of our most popular titles, Bridges by David B. Ostler, speaks to faithful members about the topic of faith crisis. The book takes an empathetic approach, teaching its readers how to build bridges of compassion and understanding with those whose faith has been challenged by historical or social issues within the Church. Read widely by teachers of Church Seminaries and Institutes, Bridges is a must-have for anyone who knows of family members, friends, or ward members who struggle with faith. | |

|

Miracles Among the Rubble by Carol R. Gray is one of the most loved books by reviewers. In heart-wrenching and inspiring chapters, written with her poetically unique style of expression, Carol shares her experiences of organizing and transporting relief aid for victims of the Balkan War during the early 1990s. Her stories are a testament to the extraordinary achievements of an ordinary mother, who was able to do remarkable things with nothing more than unwavering faith, the help and guidance of the Holy Ghost, and her relationship with the Savior. |

|

A best-seller, Women at Church by Neylan McBaine has been passed along to numerous local ward and stake leaders who seek ways to more fully include women at the local level. This eye-opening book is perfect for anyone who would like to better understand why many Latter-day Saint women feel marginalized in church settings and what can be done to improve women's visibility and voices in wards and stakes without challenging current doctrine or policies. |

|

Whom Say Ye That I Am? by James and Judith McConkie utilyzes up-to-date historical scholarship to explore Jesus in the context of first-century Palestine and Jewish culture. This book helps Latter-day Saint readers better understand the life and ministry of Jesus of Nazareth, and how he responded to social institutions and issues in his day, all of which is still relevant to a modern audience. Perfect for readers who enjoy historical Jesus scholarship. |

|

Although united in faith, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are diverse in their cultural, social, and political perspectives. Common Ground—Different Opinions offers a collection of essays on varying topics from same-sex attraction, femisim, and race, to political partisanship, war, human evolution, and more. This is the perfect book for readers who like to carefully consider arguments from both sides of complex social issues in a ways that maintain civility, respect towards faith, and commitment to the Church. |

|

The Garden of Enid Vols. 1 and 2 collect Scott Hales's much-loved coming-of-age comic series about fictional teenager, Enid Gardner, as she explores her faith and questions in light of personal and cultural challenges. Funny, charming, sincere, and moving, The Garden of Enid is perfect for teens or anyone who remembers what it was like to be an akward teenager wondering where they fit into the world and the Gospel. |

Spring Flash Sale: Up to 88% off Select Ebooks March 24 2020

Stay at home with a great book and help take the pressure off delivery services by going paperless. From now through Easter, download select ebook titles for 30% to 88% off regular price.

Sale ends Monday, 4/12/2020

****NOTE: Due to an error, the discounts for the Kindle ebooks of Second Witness volumes 5 and 6 were not applied. They should be available at the discounted rate by Sunday*****

Insightful messages on justice, mercy, hope, community, and inspiring outlooks on the future during these difficult times. Discounted right now to just $1.99 (up to 88% off regular retail price).

|

$9.95 |

$16.99 |

$16.99 |

The message of Jesus is one of hope and healing. Spend time contemplating the life and mission of the Savior with thought-provoking and inspiring scholarship. Discounted right now to 50% off regular retail price.

|

$23.99 |

$9.99 |

$22.99 |

The Book of Mormon proclaims another witness of the mission of Jesus Christ. Deepen your knowledge and understanding of this sacred book with studies that explore its text, history, and origins. Discounted right now to 30% off regular retail price.

|

$25.99 |

$17.99 |

$20.99 |

|

$22.99 |

$17.99 |

$27.99 |

|

$27.99 |

$22.99 |

$9.99 |

|

$29.99 |

$29.99 |

$29.99 |

|

$29.99 |

$29.99 |

|

Q&A with Don Bradley, author of The Lost 116 Pages: Reconstructing the Book of Mormon's Missing Stories December 09 2019

| Download a free sample preview | Order your copy |

For readers less familiar with the "lost 116 pages" can you provide a brief synopsis of what they were and how they became lost?

After Joseph Smith dictated to scribes the first four and half centuries of the Book of Mormon’s chronicle of ancient Jewish settlers in the New World (the Nephites), the manuscript of this account was borrowed by the last of those scribes, Martin Harris. The manuscript later disappeared from Harris’s locked drawer and has been lost to history ever since. The current Book of Mormon text is therefore incomplete, substituting a shorter account for this lengthy missing narrative.

Can you piece together what most likely happened to this lost early manuscript? Does the standard narrative that Lucy Harris likely destroyed them hold up? If not, why and what other possibilities should we consider?

When the manuscript disappeared, Martin Harris initially suspected his wife of the theft. Lucy Harris had been skeptical of her husband’s investment in the book and would have had motive to interfere. Lucy Harris has been regarded as the prime suspect in the theft since the late 1800s, and it has been widely presumed that she burned the manuscript. However, the explanation that Lucy Harris burned the manuscript was first proposed as only a speculative possibility a quarter-century after the fact, but the dramatic image of the disgruntled wife throwing the pages into the flames quickly caught fire and became increasingly popular with time. The further the historical sources get from the actual theft, the more likely they are to tell this story, indicating that it was the story’s sensationalism, rather than its accuracy, that led to its popularity. The first person to have suspected Lucy Harris of the theft, her husband Martin, abandoned this theory when he learned that his estranged but devout Quaker wife had denied on her deathbed knowing what happened to the pages.

The presumption that Lucy Harris stole the pages, acted alone in doing so, and burned them has prevented investigators from looking closely at other suspects, including a number of people who had previously attempted to steal other documents and relics associated with the Book of Mormon. Former treasure digging associates of Joseph Smith had attempted several times to steal the original Book of Mormon—the golden plates. And Martin and Lucy Harris had a son-in-law, a known swindler, who once stole the “Anthon transcript” of characters copied from the plates. Fixating on Lucy Harris as the only possible thief has blinded inquirers to noticing these obvious suspects.

Despite the widespread presumption that Lucy Harris was guilty of taking and burning the manuscript, the manuscript’s ultimate fate is an open question.

You assert that the lost early manuscript might have been longer than 116 pages. Can you provide some reasoning for this? Can you also speculate on how long they may have been?

The number given for the length of the lost manuscript—116 pages—exactly matches the length of the “small plates” text that replaced that manuscript. This coincidence has led several scholars, beginning with Robert F. Smith, to propose that the length of the lost manuscript was actually unknown and the 116 pages figure was just an estimate based on the length of its replacement.

While we can’t know for sure the length of the lost manuscript, unless it turns up, we can do better than just guessing at its actual length, because we have several lines of evidence for this, all of which converge on a probable manuscript size. Joseph Smith reported that Martin scribed on the lost manuscript over a period of 64 days, which, given Joseph’s known translation rate would have produced a manuscript far larger than 116 pages. In line with this, Emer Harris, ancestor to a living Latter-day Saint apostle and brother to Martin Harris, reported at a church conference that Martin had scribed for “near 200 pages” of the manuscript before it was lost. A later interviewer recounted Martin himself reporting a similar scribal output when stating what proportion of the total Book of Mormon text he recorded. Since Martin was not the only scribe to work on the now-lost manuscript but, rather, the fifth such scribe, the manuscript as a whole would have been well in excess of the nearly 200 pages produced by Martin, likely closer to 300 pages. Other lines of evidence within the existing Book of Mormon text point to a similar length for the lost portion.

What sources are used in this book to identify what was in the Book of Mormon's lost 116 pages?

To reconstruct the Book of Mormon’s lost stories this book makes use of both internal sources from within the current Book of Mormon text and external sources beyond that text. Internal sources from the Book of Mormon include, first, accounts from the narrators of the small plates of Nephi, which cover the same time period as the lost portion of Mormon’s abridgment, and, second, narrative callbacks in the surviving remnants of Mormon’s abridgment that refer to the lost stories. External sources used in the reconstruction include statements in the earliest manuscripts of Joseph Smith's revelations describing and echoing the lost pages, statements by Joseph Smith reported by apostles Franklin D. Richards and Erastus Snow, an 1830 interview granted by Joseph Smith, Sr., a conference sermon by Martin Harris’s brother Emer Harris, and reports by several other early Latter-day Saints and friends of Martin Harris.

Can you provide a few examples of how your research into the lost early manuscript has increased your awareness of a Jewish core in the Book of Mormon text?

The research that went into this book has disclosed to me a Jewishness to the Book of Mormon that I could never have imagined. Through the lens of the sources on the lost manuscript, we can see the Jewishness in the Book of Mormon from the very start: according to Joseph Smith, Sr., the lost pages identified the Book of Mormon as beginning with a Jewish festival, namely, Passover. This Jewishness is particularly striking in the sources on the lost manuscript’s narrative of the book’s founding prophets Lehi and Nephi. Their narrative begins in that of the Hebrew Bible, at the start of the Jewish Exile. The recoverable lost-manuscript narratives of Lehi and Nephi show them seeking to build a new Jewish kingdom in the New World systematically parallel to the pre-Exile Jewish kingdom in the Old World. Having lost the biblical Promised Land, sacred city, dynasty, temple, and Ark of the Covenant, they set about re-creating these by proxy.

This Jewishness in the Book of Mormon is paralleled by a distinct Jewishness of the Book of Mormon’s coming forth. Reconstructing a chronology of the several earliest events in the Book of Mormon’s emergence shows every one of these events to have been keyed to the dates of Jewish festivals. In ways not previously appreciated, the Book of Mormon is a richly and profoundly Judaic book.

In your book, you discuss temple worship among the Nephites. Can you summarize some of your findings?

Temple worship stands at the center of Nephite life and of the Book of Mormon’s narrative. The early events of Nephite history, as chronicled in the present Book of Mormon text and fleshed out further in the sources on the book’s lost manuscript, all build toward the ultimate goal of re-establishing Jewish temple worship in a new promised land. Re-establishing such worship required constructing a system closely parallel to that of Solomon’s temple. To meet the requirements of the Mosaic Law, the Nephites would have needed substitutes for the biblical high priest and Ark of the Covenant, with their associated sacred relics. Accordingly, the Nephite sacred relics—the plates, interpreters, breastplate, sword of Laban, and Liahona—systematically parallel the relics of the biblical Ark and high priest, showing how closely temple worship in the Book of Mormon was modeled on temple worship in the Bible.

In what ways are the doctrines in the early lost Book of Mormon manuscript reflected in the doctrines of early Mormonism?

Earliest Mormonism has sometimes been understood as primarily a form of Christian primitivism, the New Testament-focused nineteenth-century movement to restore original Christianity. Yet already when we explore the earliest Mormon text, the lost portion of the Book of Mormon, we find a whole-Bible religion, one weaving Christian primitivist, Judaic, and esoteric strands into a distinctively Mormon restorationist tapestry of faith.

The Book of Mormon’s focus on the temple is also very Mormon. Temple worship among the Nephites not only echoes ancient Jewish temple worship, but it also anticipates temple worship among the Latter-day Saints. The recoverable narratives of the Book of Mormon’s lost pages portray the Nephite temple as not only a place in which sacrifices are performed but also one in which higher truths are taught in symbolic form, human beings learn to speak with the Lord through the veil, and people can begin to take on divine attributes.

What are you hoping readers will gain from your book?

This book’s earliest seed was my childhood curiosity about the Book of Mormon’s lost pages. That seed grew in adulthood when I realized how knowing more about the Book of Mormon’s lost pages could illuminate its present pages. On one level, this new book is a book about the Book of Mormon’s lost text, pursuing the mystery of what was in the lost first half of Mormon’s abridgment. On another level, this is a book about understanding more deeply the Book of Mormon text we do have, since the last half of any narrator’s story is best understood in light of the first half. Researching what can be known about the lost manuscript has helped me to more fully recognize the Book of Mormon’s richness, understand its messages and meanings, and grasp its power as a sacred text. My hope is that recapturing some of the long-missing contexts behind our Book of Mormon will also expand others’ understanding of and appreciation for this remarkable foundational scripture of Latter-day Saint faith and inspire readers to delve deeper into the Book of Mormon.

Don Bradley

December 2019

Christmas Gift Sale: 30% off select titles! November 29 2019

Christmas Gift Sale: 30% off select titles*

Looking for the perfect gifts for the book lover in your life? Get 30% off select titles now through Dec 18.

**Free pickup is available for local customers. See below for details.**

Sale ends Wednesday, 12/18/2019

|

$20.95 |

$21.95 |

$27.95 |

|

|

$26.95 |

$21.95 |

$19.95 |

|

|

$20.95 |

$27.95 |

$25.95 |

|

|

$26.95 |

$34.95 |

$34.95 |

|

|

$20.95 |

$19.95 |

||

|

$34.95 |

$36.95 |

$29.95 |

|

|

$34.95 |

$15.95 |

||

|

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

|

|

$49.95 |

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

|

|

|

COMPLETE SET $249.70 |

FREE PICKUP FOR LOCAL CUSTOMERS

Enter PICKUP into the discount code box at checkout to avoid shipping and pick up the order from our office in Sandy, Utah.

Pickup times available by appointment only. Email order@koffordbooks.com to schedule your pickup time.

*Offers valid for U.S. domestic customers only. Limited to available supply.

Q&A with Bradley Kramer, author of Gathered in One: How the Book of Mormon Counters Anti-Semitism in the New Testament September 16 2019

| Download a free sample preview | Order your copy |

Q: For some, hearing that the New Testament contains anti-Semitic language can be challenging. Can you provide a few examples of anti-Semitic rhetoric in the New Testament?

A: Yes. However, first I would like to clarify that I do not think that the New Testament as a whole is anti-Semitic. I do think that the New Testament contains many anti-Semitic statements, anti-Semitic portrayals, anti-Semitic settings, and anti-Semitic structuring elements that together form a kind of literary tide that pulls its readers towards an anti-Semitic point of view, but that is not the same as saying the entire New Testament is anti-Semitic or that anti-Semitism is its major theme.

The Gospel of John, for instance, not only contains a statement where “the Jews” are told that their father is the devil (John 8:44), but they are portrayed explicitly as questioning Jesus (2:18), as accusing him of being in league with the devil (8:48), and as instilling fear in his followers (7:13; 19:38; 20:19). In this Gospel, “the Jews” function as a foil to everything Jesus stands for and teaches. They are from beneath while Jesus is from above; they are of this world while Jesus is not (8:22-23), and they, unlike the enlightened Jesus, love “darkness rather than light, because their deeds are evil” (3:19).

The Gospel of Matthew reinforces this view of Jews through its portrayal of Pharisees. In this Gospel, Pharisees are hypocritical (Matt. 16:3), judgmental (9:11), rule-bound (12:2), scheming (v.14), stupid (v. 24), sign-seeking (v. 38), superficial (15:1), easily offended (v.12), spiritually blind (v. 14), corrupt (12:33), petty (23:23), tricky (22:15), prideful (16:6), and murderous (12:14). True, the Pharisees are only a subgroup of Jews, but without many examples of other subgroups acting differently, they seem to represent Jews as a totality.

In addition, the Gospel of Matthew uses settings to undermine the viability and validity of Jewish practices. The Last Supper, for instance, is set as a Passover Seder and shows Jesus commenting on two of its most important elements: the bread and the wine. However, in this Gospel, the Mosaic meanings of these elements are not mentioned or discussed as stipulated by the Law of Moses (Ex. 12:25–27). Instead, they are presented simply as food items that have lost their Mosaic meaning and can, therefore, be easily repurposed as memorials of Jesus’s soon to-be-dead body and spilt blood. In this way, the Gospel of Matthew presents Passover, much like the Jews themselves, as something devoid of true spirituality and in need of replacement.

Q: Is there scholarly consensus regarding anti-Semitism in the New Testament? Can you provide examples of scholarly debate on the topic?

A:I think so, yes. Many scholars, however, prefer to use the term “anti-Judaic,” feeling that the New Testament attacks Jews more as members of a certain faith, which can change, than as members of an ethnic or genetic group, which cannot. I have elected to use “anti-Semitic” in my book because 1) most of my sources use that term, 2) “anti-Semitic” is the more common, inclusive term, and 3) in practice the distinction between these two approaches is not always clear—even in the New Testament. Jesus in the Gospel of John, for instance, does not tell “the Jews” that the devil is their spiritual leader; he says that the devil is their “father” (John 8: 44). Similarly, in Matthew the Jewish multitude cries out for his blood to be upon their “children, not upon their religious descendants (Matt. 27:25).

Scholars, as well as many devoted Christian ministers, are disturbed by this scene in the Gospel of Matthew. It seems to brand all Jews throughout time as “Christkillers” and has been used to justify numerous anti-Jewish atrocities. As a result, many of these scholars, ministers, and laypeople deny that it ever happened. They point out that there is no record of any Roman governor ever releasing prisoners on Passover and question the logic of such a custom. After all, why would a Roman official charged with keeping the peace run the risk of releasing his most dangerous enemies back into society? It makes no sense.

These scholars and ministers similarly dispute the Gospels’ portrayal of Pilate as a spiritually ambivalent government official who could be swayed by the voice of a Jewish multitude. According to Roman records, not only did Pilate place Roman images inside the Temple precincts in direct opposition of the will of his subjects, but he also confiscated Temple funds when they refused to pay their taxes. Furthermore, when people gathered before him to protest, he had his soldiers disguise themselves, infiltrate the crowd, and slaughter them all.

The majority of scholars and ministers see Pilate as a merciless ruler who would have had no qualms whatsoever about crucifying Jesus. However, by doing so, Pilate presented early Christians with a problem. After all, they had to live and work and worship within the Roman Empire. It would not be wise to paint a Roman official as a murderer, particularly as the murderer of the Son of God. Many scholars and ministers, therefore, see this scene as a fictional embellishment designed to shift the blame for Jesus’s death from the Romans to the already despised Jews.

Q: Can you provide an example or two of how the Book of Mormon counters anti-Semitism in the New Testament?

A: I can think of no more powerful condemnations of anti-Semitic behavior than these:

O ye Gentiles, have ye remembered the Jews, mine ancient covenant people? Nay; but ye have cursed them, and have hated them, and have not sought to recover them. But behold, I will return all these things upon your own heads; for I the Lord have not forgotten my people. (1 Ne. 29:5)

Yea, and ye need not any longer hiss, nor spurn, nor make game of the Jews, nor any of the remnant of the house of Israel; for behold, the Lord remembereth his covenant unto them, and he will do unto them according to that which he hath sworn. (3 Ne. 29:8)

Furthermore, these are not simply official declarations issued by a church or statements from an ecclesiastical leader. In the former, it is God who chastises non-Jews (probably Christians) for persecuting Jews; and in the latter, it is Mormon, a prophet of God, who commands these same Christians to cease oppressing the Jews.

Also, notice that these condemnations do not comment upon any particular passage in the New Testament, nor do they challenge the veracity of any specific New Testament event. However, given their clarity of expression, they make it very difficult for Christians to interpret the New Testament anti-Semitically.

In this way, the Book of Mormon does not change the New Testament’s words or call into question their ability to convey divine messages to their readers directly. However, for believers, it alters how the New Testament’s words are understood. When joined with the New Testament in the Christian canon, the Book of Mormon overwhelms the anti-Semitic statements, portrayals, settings, and structural elements with more numerous and more sweeping pro-Jewish statements, portrayals, settings, and structural elements of its own. In this way, the Book of Mormon turns the literary tide in the New Testament and causes it to flow in the opposite direction.

Q: How does the Book of Mormon limit Jewish involvement in Jesus’ death?

A: For the most part, the prophets in the Book of Mormon seems more interested in what Jesus’s death accomplished than in who killed him. Nephi, for instance, recounts his vision of Jesus’s death saying only that Jesus “was lifted up upon the cross and slain for the sins of the world” without specifying who did the lifting (1 Ne. 11:33), and Abinadi similarly prophecies that Jesus will be “led, crucified, and slain” again without mentioning who will do the leading, crucifying, and slaying (Mosiah 15:7). The same is true for Samuel the Lamanite (Hel. 13:6) and even Jesus (3 Ne. 11:14).

Furthermore, when these prophets do attempt to identify Jesus’s killers, they use vague terms such as “the world” or “wicked men” (1 Ne. 19:7–10), or they employ phrases that, while they may appear at first to indict all Jews everywhere, actually absolve the majority of Jews of any involvement whatsoever in Jesus’s death. Jacob’s “they at Jerusalem” (2 Ne. 10:5), for example, may seem to some readers to indicate that all Jews participate somehow in Jesus’s crucifixion. These readers link this phrase with “the Jews” in verse 3 and see it as affirming universal Jewish culpability regarding Jesus’s death. However, during Jesus’s lifetime, only a small percentage of the world’s Jews lived in Jerusalem. During that time, most Jews were still residing in Babylon or were scattered throughout the eastern Mediterranean and beyond—as Jacob, who as one of the most far-flung of these Jews, knew very well.

In other words, instead of serving as a synonym of “the Jews,” “they at Jerusalem” functions as the last element in a grammatical sequence that shrinks the number of Jews connected to Jesus’s death from all Jews everywhere to “those who are the more wicked part of the world” to just those Jews living in Jerusalem during the early first century. In a similar way, 2 Nephi 10 also softens “they shall crucify him” of verse 3 to “they . . . will stiffen their necks against him, that he be crucified” and complicates their complicity by stating in verse 5 that they do so not because of some deep-seated personal conviction but “because of priestcrafts and iniquities.”

Q: What is supersessionism and how does the Book of Mormon refute it?

A: Supersessionism is the traditional Christian doctrine that the Jews have been disobedient for so long, failing to follow their own law as well as murdering its originator (Jesus), that their covenantal connection to God has been revoked and they have been replaced by Christian Gentiles. Statements in the Book of Mormon clearly refute this notion by confirming that the Jews remain God’s “covenant people” (2 Ne. 29:4–5) even after Jesus’s death (Morm. 3:21), and by affirming that despite being scattered “upon all the face of the earth,” the Jews will one day be “armed with righteousness and with the power of God in great glory” (1 Ne. 14:14), that they will be delivered from their enemies (2 Ne. 6:17), and that pure people everywhere will seek “the welfare of the ancient and long dispersed covenant people of the Lord” (Morm. 8:15).

In addition to these statements, the portrayal of the Nephites and Lamanites further reinforces the Jews’ ongoing covenantal connection to God. In the Synoptic Gospels, Jews, as Pharisees, are portrayed as so hypocritical and murderous (at least towards Jesus) that it is hard to see them as continuing in God’s covenant. In the Book of Mormon, Nephites also struggle with hypocrisy as do the Lamanites with murder, and yet never are these New World Jews removed from God’s covenant or detached from God’s care. Missionaries go to them, and often they repent, but even when they do not and their civilization disintegrates into self-destructive chaos, God continues to seek after their descendants and sees them always as heirs to the covenantal promises given to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Q: How should Latter-day Saints relate to Jews?

A: With charity, just like Nephi (2 Ne. 33:8), and not as potential converts. It is significant that the Book of Mormon never uses the words “convert” or “conversion” in connection with Jews. Instead, it employs “persuade” and “convince,” and presents Jesus as the only person authorized to do this persuading and convincing. As he tells the Nephites:

And then will I gather them in from the four quarters of the earth; and then will I fulfil the covenant which the Father hath made unto all the people of the house of Israel. . . . And then will I remember my covenant which I have made unto my people, O house of Israel, and I will bring my gospel unto them. (3 Ne. 16:5, 11)

This repetition of the pronoun “I” in this passage and in 3 Ne. 21:1 indicates to me that Christians should not press Jews to accept Jesus. They should instead have enough faith in their Master to let him do what he has covenanted to do without any help or interference from them.

Christians should embrace Jews as brothers and sisters in God’s covenant, as true friends with whom they can talk, play, work, worship, hang out, enjoy, and learn from, especially in regards to the Scriptures. As Nephi reminds his readers:

I know that the Jews do understand the things of the prophets, and there is none other people that understand the things which were spoken unto the Jews like unto them, save it be that they are taught after the manner of the things of the Jews. (2 Ne. 25:5)

Q: What are you hoping readers will gain through this book?

A: I hope my readers will see more clearly just how the Book of Mormon can augment and enhance the Bible without undermining its scriptural authority or reliability. I hope they will also feel a closer, more informed, more appreciative connection with Jews. I think many Christians are fairly ignorant about Jews and are somewhat split in their opinion of them. Through movies such as “Schindler’s List,” “Denial,” and “The Pianist,” they may feel sympathetic towards Jews because of persecutions they have suffered and the pains they have endured. However, because of the New Testament, they may also be inclined to see Jews as chronic nitpickers who hypocritically follow superficial religious practices.

With this book, I hope to resolve this difference by showing my readers that there is more to the Jews than is offered in the New Testament, that Mosaic practices remain relevant today, that the Law of Moses has been observed admirably by an admirable people; and that Jews have much to teach Christians religiously, ethically, and scripturally. They certainly have taught me much.

Bradley J. Kramer

September 2019

Preview Gathered in One: How the Book of Mormon Counters Anti-Semitism in the New Testament August 23 2019

Gathered in One:

How the Book of Mormon Counters Anti-Semitism

in the New Testament

Download a preview here or view below.

Since the Holocaust, a growing consensus of biblical scholars have come to recognize the unfair and misleading anti-Semitic rhetoric in the New Testament—language that has arguably contributed to centuries of violence and persecution against the Jewish people.

In Gathered in One, Bradley J. Kramer shows how the Book of Mormon counters anti-Semitism in the New Testament by approaching this most Christian of books on its own turf and on its own terms: literarily, by providing numerous pro-Jewish statements, portrayals, settings, and structuring devices in opposition to similar anti-Semitic elements in the New Testament; and scripturally, by connecting with it as a peer, as a divine document of equal value and authority, which can add these elements to the Christian canon (as the Gospel of John can add elements to the Gospel of Matthew) without undermining its authority or dependability.

In this way, the Book of Mormon effectively “detoxifies” the New Testament of its anti-Semitic poison without weakening its status as scripture and goes far in encouraging Christians to relate to Jews respectfully, not as enemies or opponents, but as allies, people of equal worth, importance, and value before God.

Flash Sale: 40%-63% off Mormon theology titles! October 25 2018

Friday, Oct 26 through Monday, Oct 29. Theology titles by James McLachlan, Blake Ostler, Adam Miller, Joseph Spencer, James Faulconer, Jacob Baker, Blair Van Dyke, Loyd Ericson, Charles Inouye, Charles Harrell, Robert Millet, and more...Book of Mormon Flash Sale: 40%-64% off! September 20 2018

Friday, Sep 21 through Monday, Sep 24

In commemoration of Joseph Smith receiving the golden plates on September 22, 1827, we are pleased to offer a sale on the following Book of Mormon titles:*

Ebooks

|

$20.99 |

$27.99 |

$22.99 |

|

$27.99 |

$9.99 |

Print Books

|

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

|

$49.95 |

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

|

$34.95 |

|

$129.95 |

*Offer valid for US domestic customers only. Print book sale limited to available supply.

Q&A Part 2 with the Editors of The Expanded Canon: Perspectives on Mormonism & Sacred Texts September 11 2018

Hardcover $35.95 (ISBN 978-1-58958-637-6)

Part 2: Q&A with Brian D. Birch (Part 1)

Q: When and how did the Mormon Studies program at UVU launch?

A: The UVU Mormon Studies Program began in 2000 with the arrival of Eugene England. Gene received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to explore how Mormon Studies could succeed at a state university. A year-long seminar resulted that included a stellar lineup of consultants and guest scholars. From that point forward, the Religious Studies Program has developed multiple courses complemented by our annual Mormon Studies Conference and Eugene England Lecture—to honor Gene’s tragic and untimely passing in 2001. The program also hosts and facilitates events for independent organizations and publications including the Society for Mormon Philosophy and Theology, the Dialogue Foundation, the Interpreter Foundation, Mormon Scholars in the Humanities, Association for Mormon Letters, and others.

Q: How is the UVU Mormon Studies program distinguished from Mormon Studies programs that have emerged at other campuses?

A: Mormon Studies at UVU is distinguished by the explicitly comparative focus of our work. Given the strengths of our faculty, we have emphasized courses and programming that addresses engagement and dialogue across cultures, faith traditions, and theological perspectives. Permanent course offerings include Mormon Cultural Studies, Mormon Theology and the Christian Tradition, Mormon Anthropology, and Mormon Literature. Our strengths lie in areas other than Mormon history, which is well represented at other institutions—and appropriately so. Given the nature of our institution, our events are focused first and foremost on student learning, but all our events are free and open to the public and we welcome conversation between scholars and nonprofessionals.

Q: How long has the annual UVU Mormon Studies Conference been held, and what have been some of the topics of past conferences?

A: As mentioned above, the Mormon Studies Conference was first convened by Eugene England in 2000, and to date we have convened a total of nineteen conferences. Topics have ranged across a variety of issues including “Islam and Mormonism,” “Mormonism in the Public Mind,” “Mormonism and the Art of Boundary Maintenance,” “Mormonism and the Internet,” etc. We have been fortunate to host superb scholars and to bring them into conversation with each other and the broader public.

Q: Where did the material for the first volume, The Expanded Canon, come from?

A: The material in The Expanded Canon emerged came from our 2013 Mormon Studies Conference that shares the title of the volume. We drew from the work of conference presenters and added select essays to round out the collection. The volume is expressive of our broader approach to bring diverse scholars into conversation and to show a variety of perspectives and methodologies.

Q: What are a few key points about this volume that would be of interest to readers?

A: Few things are more central to Mormon thought than the way the tradition approaches scripture. And many of their most closely held beliefs fly in the face of general Christianity’s conception of scriptural texts. An open or expanded canon of scripture is one example. Grant Underwood explores Joseph Smith’s revelatory capacities and illustrates that Smith consistently edited his revelations and felt that his revisions were done under the same Spirit by which the initial revelation was received. Hence, the revisions may be situated in the canon with the same gravitas that the original text enjoyed. Claudia Bushman directly addresses the lack of female voices in Mormon scripture. She recommends several key documents crafted by women in the spirit of revelation. Ultimately, she suggests several candidates for inclusion. As the Mormon canon expands it should include female voices. From a non-Mormon perspective, Ann Taves does not embrace a historical explanation of the Book of Mormon or the gold plates. However, she does not deny Joseph Smith as a religious genius and compelling creator of a dynamic mythos. In her chapter she uses Mormon scripture to suggest a way that the golden plates exist, are not historical, but still maintain divine connectivity. David Holland examines the boundaries and intricacies of the Mormon canon. Historically, what are the patterns and intricacies of the expanding canon and what is the inherent logic behind the related processes? Additionally, authors treat the status of the Pearl of Great Price, the historical milieu of the publication of the Book of Mormon, and the place of The Family: A Proclamation to the World. These are just a few of the important issues addressed in this volume.

Q: What is your thought process behind curating these volumes in terms of representation from both LDS and non-LDS scholars, gender, race, academic disciplines, etc?

A: Mormon Studies programing at UVU has always been centered on strong scholarship while also extending our reach to marginalized voices. To date, we have invited guests that span a broad spectrum of Mormon thought and practice. From Orthodox Judaism to Secular Humanists; from LGBTQ to opponents to same-sex marriage; from Feminists to staunch advocates of male hierarchies, all have had a voice in the UVU Mormon Studies Program. Each course, conference, and publication treating these dynamic dialogues in Mormonism are conducted in civility and the scholarly anchors of the academy. Given our disciplinary grounding, our work has expanded the conversation and opened a wide variety of ongoing cooperation between schools of thought that intersect with Mormon thought.

Q: What can readers expect to see coming from the UVU Comparative Mormon Studies series?

A: Our 2019 conference will be centered on the experience of women in and around the Mormon traditions. We have witnessed tremendous scholarship of late in this area and are anxious to assemble key authors and advocates. Other areas we plan to explore include comparative studies in Mormonism and Asian religions, theological approaches to religious diversity, and questions of Mormon identity.

Download a free sample of The Expanded Canon

Listen to an interview with the editors

Upcoming events for The Expanded Canon:

Tue Sep 18 at 7pm | Writ & Vision (Provo) | RSVP on Facebook

Wed Sep 19 at 5:30 pm | Benchmark Books (SLC) | RSVP on Facebook

Q&A Part 1 with the Editors of The Expanded Canon: Perspectives on Mormonism & Sacred Texts August 29 2018

Hardcover $35.95 (ISBN 978-1-58958-637-6)

Part 1: Q&A with Blair G. Van Dyke (Part 2)

Q: How is the Mormon Studies program at Utah Valley University distinguished from Mormon Studies programs that have emerged at other universities?

A: The Mormon Studies program at UVU is distinguished by the comparative components of the work we do. At UVU we cast a broad net across the academy knowing that there are relevant points of exploration at the intersections of Mormonism and the arts, Mormonism and the sciences, Mormonism and literature, Mormonism and economics, Mormonism and feminism, Mormonism and world religions, and so forth. Additionally, the program is distinguished from other Mormon Studies by the academic events that we host. UVU initiated and maintains the most vibrant tradition of creating and hosting relevant and engaging conferences, symposia, and intra-campus events than any other program in the country. Further, a university-wide initiative is in place to engage the community in the work of the academy. Hence, the events held on campus are focused first and foremost for students but inviting the community to enjoy our work is very important. This facilitates understanding and builds bridges between scholars of Mormon Studies and Mormons and non-Mormons outside academic orbits.

Q: Where did the material for The Expanded Canon come from?

A: The material that constitutes volume one of the UVU Comparative Mormon Studies Series came from an annual Mormon Studies Conference that shares the title of the volume. We drew from the work of some of the scholars that presented at that conference to give their work and ours a broader audience. Generally, the contributors to the volume are not household names or prominent authors that regularly publish in the common commercial publishing houses directed at Mormon readership. As such, this volume introduces that audience to prominent personalities in the field of Mormon Studies. It is not uncommon for scholars in this field of study to look for venues where their work can reach a broader readership. This jointly published volume accomplishes that desire in a thoughtful way.

Q: What are a few key points about this volume that would be of interest to readers?

A: Few things are more central to Mormon thought than the way the tradition approaches scripture. And many of their most closely held beliefs fly in the face of general Christianity’s conception of scriptural texts. An open or expanded canon of scripture is one example. Grant Underwood explores Joseph Smith’s revelatory capacities and illustrates that Smith consistently edited his revelations and felt that his revisions were done under the same Spirit by which the initial revelation was received. Hence, the revisions may be situated in the canon with the same gravitas that the original text enjoyed. Claudia Bushman directly addresses the lack of female voices in Mormon scripture. She recommends several key documents crafted by women in the spirit of revelation. Ultimately, she suggests several candidates for inclusion. As the Mormon canon expands it should include female voices. From a non-Mormon perspective, Ann Taves does not embrace a historical explanation of the Book of Mormon or the gold plates. However, she does not deny Joseph Smith as a religious genius and compelling creator of a dynamic mythos. In her chapter she uses Mormon scripture to suggest a way that the golden plates exist, are not historical, but still maintain divine connectivity. David Holland examines the boundaries and intricacies of the Mormon canon. Historically, what are the patterns and intricacies of the expanding canon and what is the inherent logic behind the related processes? Additionally, authors treat the status of the Pearl of Great Price, the historical milieu of the publication of the Book of Mormon, and the place of The Family A Proclamation to the World. These are just a few of the important issues addressed in this volume.

Q: What is your thought process behind curating these volumes in terms of representation from both LDS and non-LDS scholars, gender, race, academic disciplines, etc?

A: Mormon Studies programing at UVU has always been centered on solid scholarship while simultaneously broadening tents of inclusivity. To date, we have invited guests that span spectrums of thought related to Mormonism. From Orthodox Judaism to Secular Humanists; from LGBTQ to opponents to same-sex marriage; from Feminists to staunch advocates of male hierarchies, all have had a voice in the UVU Mormon Studies Program. Each course, conference, and publication treating these dynamic dialogues in Mormonism are conducted in civility and the scholarly anchors of the academy. Given our disciplinary grounding, our work has expanded the conversation and opened a wide variety of ongoing cooperation between schools of thought that intersect with Mormon thought.

Download a free sample of The Expanded Canon

Listen to an interview with the editors

Tue Sep 18 at 7pm | Writ & Vision (Provo) | RSVP on Facebook

Wed Sep 19 at 5:30 pm | Benchmark Books (SLC) | RSVP on Facebook

A Very Brief History of D&C Section 132: The Plural Marriage Revelation February 14 2018

Section 132 of the Doctrine and Covenants was the last of Joseph Smith’s formal written revelations and it was a watershed in Mormonism for many reasons. Like many of Joseph Smith’s early revelations, the revelation was given to an individual, not a community. Its target was his own wife, Emma Hale Smith, largely in response to her rejection of plural marriage. Polygamy, the main theme of the July 1843 revelation, is a complex subject in Mormonism. This short work can only hope to discuss a few aspects that relate specifically to what is now Section 132 of the Doctrine and Covenants, and the impact that this revelation has had on Mormonism.

Mormon polygamy essentially began in Nauvoo. One of its functions was to serve as a threshold of loyalty to Joseph Smith. Taking the step of participating in polygamy was a high-cost social commitment for women and men. Polygamy not only tested loyalty to Smith, it might have even increased it—and not just while he lived. Joseph Smith took enormous risk in introducing polygamy to any individual. While he generally selected men and women who were already close to him and had demonstrated their commitment to Mormonism, it was dangerous to challenge some of the most fundamental boundaries of the religious and social landscape. Some dissented, such as first presidency counselor William Law and his wife Jane Law, both who later publicly opposed Smith. That opposition joined a sequence of events terminating in Smith’s assassination. After Smith’s death, church leaders who were among the insiders of plural marriage became his de facto successors.

In Utah, the Church faced increasing public opposition to the practice of “plurality.” Controversy flared as Utah transitioned from its hoped-for independent nation status into a territory of the United States. The territorial selection of officials brought federal appointees to the Mormon stronghold. Shocked by polygamy and Mormon control of the political process, those federal appointees left the territory with stories of obstructionism and wives in abundance among elite Mormon men. Those tales led LDS leadership to publish two relatively secret texts up to that point: the plural marriage revelation (now D&C 132), and an April 3, 1836 vision of Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery in the Kirtland, Ohio temple (now D&C 110). This public reveal of polygamy in 1852 solidified Washington’s opposition to Utah’s statehood. That building opposition (later called the “Raid” for the practice of U.S. Marshalls hunting polygamists) ultimately led the First Presidency to curtail the practice and preaching of plural marriage in Utah at the end of the 1880s. Public claims that the Church was still allowing new plural marriage in abundance placed heavy pressures on Church President Wilford Woodruff. After prayerful and careful consideration, Woodruff produced a document that denied current authorization of plural marriages in Utah. After meeting with fellow leaders over the document, it was edited to the succinct “Manifesto” (now Official Declaration 1), a press release statement that advised the abandonment of contracting plural marriage where it violated the law.

The statement was not intended to give the idea that D&C 132 was now void. And the psychological, sociological, metaphysical, and religious structures founded on it would take time to move and modify. Minutes and diaries of LDS apostles of the period show that many leaders thought the 1890 announcement must be temporary, that God would open the way to public polygamy once again. They, like Joseph Smith before them, saw their religious obligation as superior to their public political stance. Their commitment to the revelation and its claim as a part of the “restoration of all things” made it difficult to universally abandon the practice. Former Church President John Taylor and Woodruff himself had produced written revelations encouraging continued plural marriage. The result of these cross-pressures was that church-leader-sponsored polygamy continued through the next two decades, though in small and ever dwindling numbers. Complete termination seemed on the order of abandoning baptism or the temple endowment. The election of apostle Reed Smoot to the U.S. Senate firmed the LDS Church’s public opposition to post-manifesto polygamy, an opposition fueled strongly by Smoot himself. The plural marriage revelation formed a paradoxical cornerstone of Mormon belief in this environment as its sealing subtext became the core logic of the doctrine of eternal family over against its placing of polygamy as the higher law. Gradually, church leaders came to complete unity over ending all exceptions to public bans of the practice.

As Mormonism publicly forgot polygamy and embraced the role of quintessential clean-living white Americans, their position as an Intermountain West institution was accepted as the home of teetotaling, disciplined, and largely ordinary folk with quaint beliefs in an enchanted past. It was when LDS temples began to invade Christian fundamentalist home turf in places like Dallas and Atlanta that the plural marriage revelation again became a source of criticism among counter-cult ministries and a growing ex-Mormon publishing industry.

Section 132 never underwent the same textual expansion-contraction cycle that marked many of Smith’s other revelations during his lifetime. His life ended too soon for any revisions. It is nevertheless true that in many ways the July 12, 1843 plural marriage revelation has affected the course of Mormonism for nearly two centuries; and it was redacted, not with pen and ink, but with selective reading that shifted its focus from plural marriage onto eternal monogamous marriage. Yet, many important themes in current Mormonism are based on narratives derived from the plural marriage revelation. Section 132 is a deeply-embedded component of Church teachings on eternal family, the approach of the Church towards gay rights and marriage, and social issues such as the role of women within the Church and family life. It is not an exaggeration to say that the revelation on polygamy is one of the cornerstones that underlies what Mormonism is today.

William Victor Smith received a PhD in mathematics at the University of Utah, where he also studied history under Davis Bitton. After post-doctoral work at Texas Tech University, he worked at the University of Mississippi, the University of Pau, and Brigham Young University. He has been published in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought and is the admin for the Book of Abraham Project website. He currently lives with his wife Gailan in Orem, Utah. Together they have six children.

Mark your calendar

Please join us on Tuesday, March 13th at Writ & Vision in Provo for a special roundtable discussion of Textual Studies of the Doctrine and Covenants: The Plural Marriage Revelation. Panelists include Bill Smith, Lindsay Hansen Park, and Don Bradley. The event begins at 7:00 PM and is free to attend. Writ & Vision: 274 W Center Street, Provo, UT.

Textual Studies of the Doctrine & Covenants: The Plural Marriage Revelation

By William V. Smith

Part of the Contemporary Studies in Scripture series

Available February 27, 2018

Pre-order your copy

Q&A with William V. Smith for Textual Studies of the Doctrine and Covenants: The Plural Marriage Revelation February 07 2018

Available February 27, 2018

Pre-order Your Copy Today

Q: Give us a little background into how you became interested in researching plural marriage?

A: Section 132 is Joseph Smith’s final revelation text and in some ways, it had a greater influence over his subsequent legacy than any other text aside from the Book of Mormon. My main historical interest in Mormonism is its preaching texts. Joseph Smith’s revelation texts, together with his own sermon corpus, are connected in many ways to that broader Mormon and Protestant sermon culture. The revelation had deep influence in the relationships between Territorial and statehood Utah and the United States; and made for interesting common ground narratives with other segments of the social landscape in America, as well as indelibly marking the boundaries between Mormon faithfulness and Protestant America even into the twenty-first century. Those stories fascinated me.

Q: It's a common misconception that Joseph Smith first learned about polygamy through the plural marriage revelation, when, in fact, he had already been practicing it for a few years prior to receiving it. If not to introduce it, what was the purpose of the revelation when it was received?

A: The revelation arises from a request by Hyrum Smith, but that story has multiple axes. His brother Hyrum seems to have been convinced of the virtue of polygamy out of its promise of being eternally with his deceased first wife, Jerusha Barden, while not abandoning his second wife, Mary Fielding. This domestic concept of heaven was the logic of polygamy for Hyrum. Emma Smith, first wife of Joseph, was deeply opposed to her husband’s polygamy for a multitude of reasons. Jealousy was at issue, but perhaps more-so the state of the Mormon community and its political and social predicament. Hyrum apparently believed his own adaption to polygamy could convince Emma of its virtue and bring Joseph and Emma into harmony. The result was a text largely directed to Emma Smith and very much a contemporary construction, yet it served to drive future social, religious, legal, and political tensions—including various schisms within the Church and the Smith family, the rise of Brigham Young and the apostles, and the long territorial status of Utah.

Q: In your book you show how the revelation points to new theological ideas and priesthood structures that Joseph introduced during the Nauvoo period. What are some of these new ideas, and why are they important to understanding the revelation?

A: The revelation brings to a climax many threads from 1830s Mormonism. For example, a refined picture of heaven, church hierarchy, and the Abrahamic story. It also reflects significant discourse in Nauvoo regarding coping with loss, heavenly progression, etc. Some of the theological threads originated with an event in June 1831. It was during a conference of that month that Joseph Smith introduced the “high priesthood.” Together with this introduction came the concept of “sealing up to eternal life.” Could a person, even a whole congregation, be guaranteed a seat at the Throne of Grace in this life? The high priesthood had the power to do this. I take some time in the book to explore the relationship of the high priesthood and its divisional office of patriarch with the idea of sealing, and how this idea became fully realized with the Nauvoo incarnation of sealing and priesthood. The plural marriage revelation draws on some elements of Smith’s Nauvoo preaching in public and private, some of which shows an interesting contrast between Smith’s public sermons and later interpretations that were prominent in Utah.

Q: What are some of the lasting impacts of the plural marriage revelation that are affecting Mormonism today?

A: Many important themes in current Mormonism are based on narratives derived from the plural marriage revelation. One of these is serial polygamous marriages where a man may remarry after the death of a spouse and have hopes that both households will be intact in the heavens. Women are not eligible for such practices. Temple practices of sealing, marriage, and family are traced to section 132, though not explicitly. The “Proclamation on the Family” is largely founded in nineteenth-century values that find textual support in the plural marriage revelation. The long defense of polygamy through the beginning of the twentieth century shaped the Church’s political attitudes in Utah to a great extent. Utah’s reaction to that political struggle was to position Mormons as ultra-Americans, rather than members of a dissenting sect of outsiders. These are just a few areas where the plural marriage revelation has had a large impact on Mormons historically and in the present.

Q: What are you hoping that readers will gain from reading Textual Studies of the D&C: The Plural Marriage Revelation?

A: My hope is that readers will come away with an increased respect for the early Mormons (especially women) who lived during the time of the practice of polygamy and its ending; as well as the power the revelation had over Mormon teaching and thought. The revelation is rarely quoted or referenced in the LDS church of the last nearly one hundred years, which was influenced by the political tension between Washington and Utah. I hope readers will gain a greater understanding of the roles that culture, the migration westward, public perception, and social change had on the public views of Latter-day Saints. Section 132 is a deeply-embedded component of Church teachings on eternal family, the approach of the Church towards gay rights and marriage, and social and political issues like the ERA and the role of women within the Church. It is not an exaggeration to say that the revelation on polygamy is one of the cornerstones that underlies what Utah and the LDS church are today.

Pre-order Your Copy Today

Please join us on Tuesday, March 13 at Writ & Vision in Provo, UT, for a special roundtable discussion and book signing for Textual Studies of the Doctrine and Covenants: The Plural Marriage Revelation. The roundtable discussion will feature Bill Smith, Don Bradley, and Lindsay Hansen Park. The event begins at 7:00 PM and is free to the public.

5 Things We Learned About the Jesus of Nazareth January 22 2018

Consider the many different ways Jesus has been portrayed over the centuries or the ways his name has been employed in support of this or that cause. N. T. Wright, a prominent Jesus scholar and Anglican Bishop, observes that he is “almost universally approved of” but for “very different and indeed often incompatible reasons.” If this is the case, then we wondered what Jesus were we worshiping and whether that Jesus was one of our own making?

During the past half-century historians have made significant strides examining the most recently discovered source materials in order to think once again about existing documents like the four Gospels. The aim was to reconstruct the Jesus who the men and women in first-century Palestine would recognize and follow. Jesus was born into an ancient society constrained by millennia of social, theological, and political practices perpetuated by the minority ruling elite and facilitated by a vast majority of souls who knew of no other way. Periodically prophets would rail against the system in the name of God. But the great, colossus of ancient Rome remained sustained through the oppression of individuals, the very individuals that Jesus came to invite into a new, righteous Kingdom.

The Jesus of history and the Gospels largely displaced the conventions of his day with regard to women and the family, as well as the social standing of the poor, the wealthy, and the outcast.

On Women:

In the twenty-first century, when issues regarding the roles of men and women in religious environments are alive and controversial, Jesus’s treatment of women was prescient. His example and the privileges afforded the first female Christians provide important perspectives. The subject takes on added significance as we appreciate the meaning of the priestly roles that women play in Latter-day Saint temples. Echoing what N. T. Wright suggests in his recent book Surprised by Scripture, we must “think carefully about where our own cultures, prejudices, and angers are taking us, and make sure we conform not to the stereotypes the world offers but to the healing, liberating, humanizing message of the gospel.” He continues, “[we live in a time when] we need to radically change our traditional pictures of what men and women are and of how they relate to one another within the church, and indeed of what the Bible says on this subject.”

On the Family:

What little Jesus had to say about the family is jarring to modern ears. He replaced the household of his day with a new universal family called the Kingdom of God where all were brothers and sisters. All were welcome: the poor and the rich, men and women, bond and free, high and low, Jew and Gentile. Members were asked to live in a communal order where everyone had what they needed.

On the Poor:

At the end of Jesus’s ministry, his priorities had not shifted from those he announced by way of the Isaiah text he read as he stood in the synagogue in Nazareth. Prior to his betrayal, Jesus spoke about the Final Judgment. He reminded those who heard him then, as well as those who hear him today, that when our lives are weighed in the balance, we will be judged not on what we know, or how many things we owned, or on how many church meetings we attended; rather, we will be judged on the basis of how well we loved our neighbors, and how well we fed the hungry, clothed the naked, cared for the sick, and visited those in need (Matt. 25:31–46).

On the Wealthy:

Matthew’s Gospel records that Jesus spoke to a “rich young man” who, by his own report, kept all the commandments in Torah, the Mishnah, and the Oral Traditions. Jesus asked him to go one step further and distribute all his wealth equally amongst the poor in order to be a part of God’s kingdom (Matt. 19:21-22). The apocryphal Gospel of Hebrews records that when the young man could not take that step, he “began to scratch his head because he did not like that command.” But then, Mark’s Gospel says, “Jesus felt genuine love for [this man]” (Mark 10:21 NLT).

Father James Martin, in a memoir on his pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 2014, writes about his encounter with the story, standing on the supposed spot where Jesus told it: “Jesus ‘loved him’? Where did that come from? I had heard this Gospel story dozens of times. How had I missed that line? . . . Those three words . . . altered the familiar story and thus altered how I saw Jesus. No longer was it the exacting Jesus demanding perfection; it was the loving Jesus offering [agency]. Now I [and we] could hear him utter those words with infinite compassion for the man. . . . Jesus explicitly offers a promise of abundance to everyone” (Jesus: a Pilgrimage, 271).

Jesus invited all to be bound to him by the “covenant of salt.”

The Covenant of Salt is a three-part obligation. The meaning of the name of the covenant would have been obvious to the men and women who followed him: salt was and is the root word of salvation and it was an enormously valuable commodity in their day. At the end of our study, we came to understand a little better what N. T. Wright observes – that what mattered most to Jesus was that his true disciples were “the kind of people through whom the kingdom will be launched on earth.” Being like Jesus meant that each of us qualified for heaven through serving his “lambs.” Being like Jesus was about loving others and thereby transforming the earth, making it a Godlike place. It was what Jesus earnestly prayed for and by example asked us to pray for: “Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven” (Matt. 6:10 KJV; emphasis added). God’s ultimate rule on earth will come about because we, as true disciples of Jesus Christ, are the light of the world and the salt of the earth (Matt.5:13, 14 KJV). We have covenanted. We have come away from this pilgrimage with a resolve to “have salt in ourselves, and have peace one with another” (Mark 9:50 KJV).

James and Judith McConkie will be speaking and signing books at Writ & Vision in Provo, Utah, on Tuesday, January 30 at 7 pm, and at Benchmark Books in Salt Lake City on Wednesday, February 7 at 5:30 pm..These events are free to the public.

James W. McConkie has JD from the S. J. Quinney College of Law at the University of Utah. His practice has focused in the area of torts and civil rights for more than four decades. He has been an adjunct professor at Westminster College teaching Constitutional law for non-lawyers. He has taught Church History and New Testament courses for BYU’s Division of Continuing Education for over 15 years with his wife Judith and is the author of Looking at the Doctrine and Covenants for the Very First Time. In 2017 he and his law partner Bradley Parker created the Refugee Justice League, a non-profit organization of attorneys and other professionals offering pro-bono help to refugees who have been discriminated against on the basis of their religion, ethnicity, or national origin.

James W. McConkie has JD from the S. J. Quinney College of Law at the University of Utah. His practice has focused in the area of torts and civil rights for more than four decades. He has been an adjunct professor at Westminster College teaching Constitutional law for non-lawyers. He has taught Church History and New Testament courses for BYU’s Division of Continuing Education for over 15 years with his wife Judith and is the author of Looking at the Doctrine and Covenants for the Very First Time. In 2017 he and his law partner Bradley Parker created the Refugee Justice League, a non-profit organization of attorneys and other professionals offering pro-bono help to refugees who have been discriminated against on the basis of their religion, ethnicity, or national origin.

Judith E. McConkie has an MFA in printmaking from BYU and a PhD in philosophy of art history and museum theory from the University of Utah. She has taught art history at the secondary and then university levels for over 40 years. She was the Senior Educator at BYU’s Museum of Art and Curator of the Utah State Capital during its major renovation project from 2004–2010. During that time she authored With Anxious Care: the Restoration of the Utah Capital. She continues to teach in BYU’s Division of Continuing Education with her husband James. She has published in Sunstone and Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Though and has presented at Sunstone’s annual symposium. Her prints and watercolors have been exhibited nationally and in the Henry Moore Gallery in London, England. She and James are the parents of three children and 12 grandchildren.

Judith E. McConkie has an MFA in printmaking from BYU and a PhD in philosophy of art history and museum theory from the University of Utah. She has taught art history at the secondary and then university levels for over 40 years. She was the Senior Educator at BYU’s Museum of Art and Curator of the Utah State Capital during its major renovation project from 2004–2010. During that time she authored With Anxious Care: the Restoration of the Utah Capital. She continues to teach in BYU’s Division of Continuing Education with her husband James. She has published in Sunstone and Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Though and has presented at Sunstone’s annual symposium. Her prints and watercolors have been exhibited nationally and in the Henry Moore Gallery in London, England. She and James are the parents of three children and 12 grandchildren.

|

Whom Say Ye that I Am? Lessons from the Jesus of Nazareth Available Jan 30, 2018 |

5 Things to Know Before Studying the Old Testament December 29 2017

Welcome to the study of the Old Testament! Latter-day Saints are about to undertake an exciting journey this year in Gospel Doctrine. The Old Testament is a fascinating book that has had a tremendous influence on the development of LDS scripture and doctrine. As we begin this journey, I have been invited to share some of the main points I would hope readers would keep in mind. For both ancient and modern Judaism, the spiritual foundation of the Hebrew scriptures is the Torah or “Law” (i.e. the opening five books traditionally ascribed to Moses). As a reflection of this tradition, I have chosen five things that I would encourage LDS readers to keep in mind—my own personal “torah,” if you will, for a religious study of the Old Testament.

1. Genesis

The Old Testament contains a variety of distinct literary genres such as law codes, proverbs, satire, erotic poetry, genealogical lists, prophecy, chronicles, and parables (just to name a few). This means that readers of the Bible should not approach a book like Chronicles, for instance, with its emphasis on sources and verisimilitude, in the same way they interpret a book such as Job or Jonah. Without a basic understanding of a text’s specific genre, readers inevitably misinterpret its intended meaning.

For example, in the King James Bible, the book of Job begins with the statement: “There was a man in the land of Uz, whose name was Job” (1:1). Yet this is not the way books typically begin in the Bible. In fact, the uniqueness of the literary construct in Hebrew led one recent scholar to render the verse as, “Once upon a time, in the land of Uz, there was a man named Job.” That opening completely changes the way readers approach the book. Reading the book of Job as a parable or a fable, rather than a historical account, changes the entire way readers relate to the story and poetry of Job. I believe that it is important, therefore, to remember that the Old Testament is not a single book, meant to be interpreted in a single manner. Rather, it is a collection of distinct literary genres from ancient Israel that should not be read as a single volume in the way a person typically reads a novel or history book.

2. Exodus

For example, parts of the Bible relate well to the LDS view concerning the corporeal (bodily) nature of God. Exodus 24:9–11 presents an account where Moses, Aaron, Nadab, Abihu, and seventy elders of Israel ascend Mount Sinai and literally see the “God of Israel” (v. 10). According to that narrative, these men not only saw God’s feet and hand, God literally joined them in eating a communal meal. In this story, God was physical, had a body, and could use it just like a human.

Yet God appears much less physical and human-like in Deuteronomy. Deuteronomy 4:12 tells its readers that when Israel approached the holy mountain, they did not see a God with a body; they only heard a voice: “ye heard the voice of the words, but saw no similitude (tmwnh); only ye heard a voice.” The Hebrew word in this passage translated as “similitude” literally means “form,” and it refers to a physical manifestation. From Deuteronomy’s perspective, God does not have a physical body and no one could see him. Latter-day Saints will therefore find some sections of the Bible to accord with their own theological views and others, perhaps, a little less so.

3. Leviticus

Since the Bible contains a variety of unique and contradictory perspectives written by separate authors over a thousand-year period, I believe that it is best for religious readers to treat the work as a sourcebook rather than a textbook. Like an anthology, a sourcebook presents readers with multiple perspectives. In order to make sense, a textbook typically presents a single specific point of view. Unfortunately, this is the way that most religious readers have traditionally approached the Old Testament.

If, however, a reader approaches the Old Testament in the way that it truly appears (i.e. as a sourcebook presenting multiple perspectives), then the collection can serve as a springboard for enlightenment, helping readers to define their own relationship to divinity. In other words, the Old Testament does not define God. Instead, it defines the way that specific groups of ancient Israelites living in a different time and place understood God.

Adopting this critical approach can help a religious reader when she feels uncomfortable about the way a specific law treats a female rape victim or when a contemporary reader feels uncomfortable with the way God commands the Israelites to completely annihilate the indigenous population of Canaan. If that perspective troubles a reader then the text can serve as a springboard helping him to define his own moral and religious convictions independent from the text.