News

New Year's Ebook Flash Sale December 27 2021

As we welcome 2022, we are pleased to offer discounted prices on select ebooks on scripture and doctrine. This sale runs from January 1–7 and is available for Kindle and Apple ebooks.

Sale ends Friday, Jan 7.

|

|

Scripture |

|

|

$27.99 |

$29.99 |

$29.99 |

|

$29.99 |

$29.99 |

$29.99 |

|

$29.99 |

$22.99 |

|

|

$18.99 |

$25.99 |

$27.99 |

|

$17.99 |

$20.99 |

$17.99 |

|

$22.99 |

$9.99 |

|

|

$22.99 |

$23.99 |

|

|

|

Doctrine |

|

|

$16.99 |

$16.99 |

|

|

$23.99 |

$23.99 |

|

|

$22.99 |

$9.99 |

|

|

$16.99 |

$22.99 |

|

|

$18.99 |

$22.99 |

Q&A with Joseph M. Spencer, author of The Anatomy of Book of Mormon Theology November 14 2021

Joseph M. Spencer, November 2021

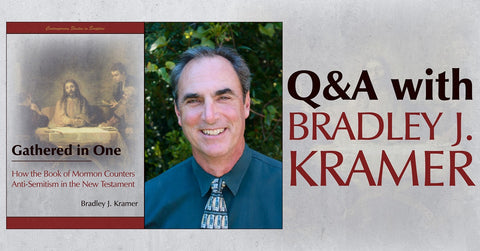

Q&A with Bradley Kramer, author of Gathered in One: How the Book of Mormon Counters Anti-Semitism in the New Testament September 16 2019

| Download a free sample preview | Order your copy |

Q: For some, hearing that the New Testament contains anti-Semitic language can be challenging. Can you provide a few examples of anti-Semitic rhetoric in the New Testament?

A: Yes. However, first I would like to clarify that I do not think that the New Testament as a whole is anti-Semitic. I do think that the New Testament contains many anti-Semitic statements, anti-Semitic portrayals, anti-Semitic settings, and anti-Semitic structuring elements that together form a kind of literary tide that pulls its readers towards an anti-Semitic point of view, but that is not the same as saying the entire New Testament is anti-Semitic or that anti-Semitism is its major theme.

The Gospel of John, for instance, not only contains a statement where “the Jews” are told that their father is the devil (John 8:44), but they are portrayed explicitly as questioning Jesus (2:18), as accusing him of being in league with the devil (8:48), and as instilling fear in his followers (7:13; 19:38; 20:19). In this Gospel, “the Jews” function as a foil to everything Jesus stands for and teaches. They are from beneath while Jesus is from above; they are of this world while Jesus is not (8:22-23), and they, unlike the enlightened Jesus, love “darkness rather than light, because their deeds are evil” (3:19).

The Gospel of Matthew reinforces this view of Jews through its portrayal of Pharisees. In this Gospel, Pharisees are hypocritical (Matt. 16:3), judgmental (9:11), rule-bound (12:2), scheming (v.14), stupid (v. 24), sign-seeking (v. 38), superficial (15:1), easily offended (v.12), spiritually blind (v. 14), corrupt (12:33), petty (23:23), tricky (22:15), prideful (16:6), and murderous (12:14). True, the Pharisees are only a subgroup of Jews, but without many examples of other subgroups acting differently, they seem to represent Jews as a totality.

In addition, the Gospel of Matthew uses settings to undermine the viability and validity of Jewish practices. The Last Supper, for instance, is set as a Passover Seder and shows Jesus commenting on two of its most important elements: the bread and the wine. However, in this Gospel, the Mosaic meanings of these elements are not mentioned or discussed as stipulated by the Law of Moses (Ex. 12:25–27). Instead, they are presented simply as food items that have lost their Mosaic meaning and can, therefore, be easily repurposed as memorials of Jesus’s soon to-be-dead body and spilt blood. In this way, the Gospel of Matthew presents Passover, much like the Jews themselves, as something devoid of true spirituality and in need of replacement.

Q: Is there scholarly consensus regarding anti-Semitism in the New Testament? Can you provide examples of scholarly debate on the topic?

A:I think so, yes. Many scholars, however, prefer to use the term “anti-Judaic,” feeling that the New Testament attacks Jews more as members of a certain faith, which can change, than as members of an ethnic or genetic group, which cannot. I have elected to use “anti-Semitic” in my book because 1) most of my sources use that term, 2) “anti-Semitic” is the more common, inclusive term, and 3) in practice the distinction between these two approaches is not always clear—even in the New Testament. Jesus in the Gospel of John, for instance, does not tell “the Jews” that the devil is their spiritual leader; he says that the devil is their “father” (John 8: 44). Similarly, in Matthew the Jewish multitude cries out for his blood to be upon their “children, not upon their religious descendants (Matt. 27:25).

Scholars, as well as many devoted Christian ministers, are disturbed by this scene in the Gospel of Matthew. It seems to brand all Jews throughout time as “Christkillers” and has been used to justify numerous anti-Jewish atrocities. As a result, many of these scholars, ministers, and laypeople deny that it ever happened. They point out that there is no record of any Roman governor ever releasing prisoners on Passover and question the logic of such a custom. After all, why would a Roman official charged with keeping the peace run the risk of releasing his most dangerous enemies back into society? It makes no sense.

These scholars and ministers similarly dispute the Gospels’ portrayal of Pilate as a spiritually ambivalent government official who could be swayed by the voice of a Jewish multitude. According to Roman records, not only did Pilate place Roman images inside the Temple precincts in direct opposition of the will of his subjects, but he also confiscated Temple funds when they refused to pay their taxes. Furthermore, when people gathered before him to protest, he had his soldiers disguise themselves, infiltrate the crowd, and slaughter them all.

The majority of scholars and ministers see Pilate as a merciless ruler who would have had no qualms whatsoever about crucifying Jesus. However, by doing so, Pilate presented early Christians with a problem. After all, they had to live and work and worship within the Roman Empire. It would not be wise to paint a Roman official as a murderer, particularly as the murderer of the Son of God. Many scholars and ministers, therefore, see this scene as a fictional embellishment designed to shift the blame for Jesus’s death from the Romans to the already despised Jews.

Q: Can you provide an example or two of how the Book of Mormon counters anti-Semitism in the New Testament?

A: I can think of no more powerful condemnations of anti-Semitic behavior than these:

O ye Gentiles, have ye remembered the Jews, mine ancient covenant people? Nay; but ye have cursed them, and have hated them, and have not sought to recover them. But behold, I will return all these things upon your own heads; for I the Lord have not forgotten my people. (1 Ne. 29:5)

Yea, and ye need not any longer hiss, nor spurn, nor make game of the Jews, nor any of the remnant of the house of Israel; for behold, the Lord remembereth his covenant unto them, and he will do unto them according to that which he hath sworn. (3 Ne. 29:8)

Furthermore, these are not simply official declarations issued by a church or statements from an ecclesiastical leader. In the former, it is God who chastises non-Jews (probably Christians) for persecuting Jews; and in the latter, it is Mormon, a prophet of God, who commands these same Christians to cease oppressing the Jews.

Also, notice that these condemnations do not comment upon any particular passage in the New Testament, nor do they challenge the veracity of any specific New Testament event. However, given their clarity of expression, they make it very difficult for Christians to interpret the New Testament anti-Semitically.

In this way, the Book of Mormon does not change the New Testament’s words or call into question their ability to convey divine messages to their readers directly. However, for believers, it alters how the New Testament’s words are understood. When joined with the New Testament in the Christian canon, the Book of Mormon overwhelms the anti-Semitic statements, portrayals, settings, and structural elements with more numerous and more sweeping pro-Jewish statements, portrayals, settings, and structural elements of its own. In this way, the Book of Mormon turns the literary tide in the New Testament and causes it to flow in the opposite direction.

Q: How does the Book of Mormon limit Jewish involvement in Jesus’ death?

A: For the most part, the prophets in the Book of Mormon seems more interested in what Jesus’s death accomplished than in who killed him. Nephi, for instance, recounts his vision of Jesus’s death saying only that Jesus “was lifted up upon the cross and slain for the sins of the world” without specifying who did the lifting (1 Ne. 11:33), and Abinadi similarly prophecies that Jesus will be “led, crucified, and slain” again without mentioning who will do the leading, crucifying, and slaying (Mosiah 15:7). The same is true for Samuel the Lamanite (Hel. 13:6) and even Jesus (3 Ne. 11:14).

Furthermore, when these prophets do attempt to identify Jesus’s killers, they use vague terms such as “the world” or “wicked men” (1 Ne. 19:7–10), or they employ phrases that, while they may appear at first to indict all Jews everywhere, actually absolve the majority of Jews of any involvement whatsoever in Jesus’s death. Jacob’s “they at Jerusalem” (2 Ne. 10:5), for example, may seem to some readers to indicate that all Jews participate somehow in Jesus’s crucifixion. These readers link this phrase with “the Jews” in verse 3 and see it as affirming universal Jewish culpability regarding Jesus’s death. However, during Jesus’s lifetime, only a small percentage of the world’s Jews lived in Jerusalem. During that time, most Jews were still residing in Babylon or were scattered throughout the eastern Mediterranean and beyond—as Jacob, who as one of the most far-flung of these Jews, knew very well.

In other words, instead of serving as a synonym of “the Jews,” “they at Jerusalem” functions as the last element in a grammatical sequence that shrinks the number of Jews connected to Jesus’s death from all Jews everywhere to “those who are the more wicked part of the world” to just those Jews living in Jerusalem during the early first century. In a similar way, 2 Nephi 10 also softens “they shall crucify him” of verse 3 to “they . . . will stiffen their necks against him, that he be crucified” and complicates their complicity by stating in verse 5 that they do so not because of some deep-seated personal conviction but “because of priestcrafts and iniquities.”

Q: What is supersessionism and how does the Book of Mormon refute it?

A: Supersessionism is the traditional Christian doctrine that the Jews have been disobedient for so long, failing to follow their own law as well as murdering its originator (Jesus), that their covenantal connection to God has been revoked and they have been replaced by Christian Gentiles. Statements in the Book of Mormon clearly refute this notion by confirming that the Jews remain God’s “covenant people” (2 Ne. 29:4–5) even after Jesus’s death (Morm. 3:21), and by affirming that despite being scattered “upon all the face of the earth,” the Jews will one day be “armed with righteousness and with the power of God in great glory” (1 Ne. 14:14), that they will be delivered from their enemies (2 Ne. 6:17), and that pure people everywhere will seek “the welfare of the ancient and long dispersed covenant people of the Lord” (Morm. 8:15).

In addition to these statements, the portrayal of the Nephites and Lamanites further reinforces the Jews’ ongoing covenantal connection to God. In the Synoptic Gospels, Jews, as Pharisees, are portrayed as so hypocritical and murderous (at least towards Jesus) that it is hard to see them as continuing in God’s covenant. In the Book of Mormon, Nephites also struggle with hypocrisy as do the Lamanites with murder, and yet never are these New World Jews removed from God’s covenant or detached from God’s care. Missionaries go to them, and often they repent, but even when they do not and their civilization disintegrates into self-destructive chaos, God continues to seek after their descendants and sees them always as heirs to the covenantal promises given to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Q: How should Latter-day Saints relate to Jews?

A: With charity, just like Nephi (2 Ne. 33:8), and not as potential converts. It is significant that the Book of Mormon never uses the words “convert” or “conversion” in connection with Jews. Instead, it employs “persuade” and “convince,” and presents Jesus as the only person authorized to do this persuading and convincing. As he tells the Nephites:

And then will I gather them in from the four quarters of the earth; and then will I fulfil the covenant which the Father hath made unto all the people of the house of Israel. . . . And then will I remember my covenant which I have made unto my people, O house of Israel, and I will bring my gospel unto them. (3 Ne. 16:5, 11)

This repetition of the pronoun “I” in this passage and in 3 Ne. 21:1 indicates to me that Christians should not press Jews to accept Jesus. They should instead have enough faith in their Master to let him do what he has covenanted to do without any help or interference from them.

Christians should embrace Jews as brothers and sisters in God’s covenant, as true friends with whom they can talk, play, work, worship, hang out, enjoy, and learn from, especially in regards to the Scriptures. As Nephi reminds his readers:

I know that the Jews do understand the things of the prophets, and there is none other people that understand the things which were spoken unto the Jews like unto them, save it be that they are taught after the manner of the things of the Jews. (2 Ne. 25:5)

Q: What are you hoping readers will gain through this book?

A: I hope my readers will see more clearly just how the Book of Mormon can augment and enhance the Bible without undermining its scriptural authority or reliability. I hope they will also feel a closer, more informed, more appreciative connection with Jews. I think many Christians are fairly ignorant about Jews and are somewhat split in their opinion of them. Through movies such as “Schindler’s List,” “Denial,” and “The Pianist,” they may feel sympathetic towards Jews because of persecutions they have suffered and the pains they have endured. However, because of the New Testament, they may also be inclined to see Jews as chronic nitpickers who hypocritically follow superficial religious practices.

With this book, I hope to resolve this difference by showing my readers that there is more to the Jews than is offered in the New Testament, that Mosaic practices remain relevant today, that the Law of Moses has been observed admirably by an admirable people; and that Jews have much to teach Christians religiously, ethically, and scripturally. They certainly have taught me much.

Bradley J. Kramer

September 2019

Book of Mormon Flash Sale: 40%-64% off! September 20 2018

Friday, Sep 21 through Monday, Sep 24

In commemoration of Joseph Smith receiving the golden plates on September 22, 1827, we are pleased to offer a sale on the following Book of Mormon titles:*

Ebooks

|

$20.99 |

$27.99 |

$22.99 |

|

$27.99 |

$9.99 |

Print Books

|

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

|

$49.95 |

$39.95 |

$39.95 |

|

$34.95 |

|

$129.95 |

*Offer valid for US domestic customers only. Print book sale limited to available supply.

Q&A Part 2 with the Editors of The Expanded Canon: Perspectives on Mormonism & Sacred Texts September 11 2018

Hardcover $35.95 (ISBN 978-1-58958-637-6)

Part 2: Q&A with Brian D. Birch (Part 1)

Q: When and how did the Mormon Studies program at UVU launch?

A: The UVU Mormon Studies Program began in 2000 with the arrival of Eugene England. Gene received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to explore how Mormon Studies could succeed at a state university. A year-long seminar resulted that included a stellar lineup of consultants and guest scholars. From that point forward, the Religious Studies Program has developed multiple courses complemented by our annual Mormon Studies Conference and Eugene England Lecture—to honor Gene’s tragic and untimely passing in 2001. The program also hosts and facilitates events for independent organizations and publications including the Society for Mormon Philosophy and Theology, the Dialogue Foundation, the Interpreter Foundation, Mormon Scholars in the Humanities, Association for Mormon Letters, and others.

Q: How is the UVU Mormon Studies program distinguished from Mormon Studies programs that have emerged at other campuses?

A: Mormon Studies at UVU is distinguished by the explicitly comparative focus of our work. Given the strengths of our faculty, we have emphasized courses and programming that addresses engagement and dialogue across cultures, faith traditions, and theological perspectives. Permanent course offerings include Mormon Cultural Studies, Mormon Theology and the Christian Tradition, Mormon Anthropology, and Mormon Literature. Our strengths lie in areas other than Mormon history, which is well represented at other institutions—and appropriately so. Given the nature of our institution, our events are focused first and foremost on student learning, but all our events are free and open to the public and we welcome conversation between scholars and nonprofessionals.

Q: How long has the annual UVU Mormon Studies Conference been held, and what have been some of the topics of past conferences?

A: As mentioned above, the Mormon Studies Conference was first convened by Eugene England in 2000, and to date we have convened a total of nineteen conferences. Topics have ranged across a variety of issues including “Islam and Mormonism,” “Mormonism in the Public Mind,” “Mormonism and the Art of Boundary Maintenance,” “Mormonism and the Internet,” etc. We have been fortunate to host superb scholars and to bring them into conversation with each other and the broader public.

Q: Where did the material for the first volume, The Expanded Canon, come from?

A: The material in The Expanded Canon emerged came from our 2013 Mormon Studies Conference that shares the title of the volume. We drew from the work of conference presenters and added select essays to round out the collection. The volume is expressive of our broader approach to bring diverse scholars into conversation and to show a variety of perspectives and methodologies.

Q: What are a few key points about this volume that would be of interest to readers?

A: Few things are more central to Mormon thought than the way the tradition approaches scripture. And many of their most closely held beliefs fly in the face of general Christianity’s conception of scriptural texts. An open or expanded canon of scripture is one example. Grant Underwood explores Joseph Smith’s revelatory capacities and illustrates that Smith consistently edited his revelations and felt that his revisions were done under the same Spirit by which the initial revelation was received. Hence, the revisions may be situated in the canon with the same gravitas that the original text enjoyed. Claudia Bushman directly addresses the lack of female voices in Mormon scripture. She recommends several key documents crafted by women in the spirit of revelation. Ultimately, she suggests several candidates for inclusion. As the Mormon canon expands it should include female voices. From a non-Mormon perspective, Ann Taves does not embrace a historical explanation of the Book of Mormon or the gold plates. However, she does not deny Joseph Smith as a religious genius and compelling creator of a dynamic mythos. In her chapter she uses Mormon scripture to suggest a way that the golden plates exist, are not historical, but still maintain divine connectivity. David Holland examines the boundaries and intricacies of the Mormon canon. Historically, what are the patterns and intricacies of the expanding canon and what is the inherent logic behind the related processes? Additionally, authors treat the status of the Pearl of Great Price, the historical milieu of the publication of the Book of Mormon, and the place of The Family: A Proclamation to the World. These are just a few of the important issues addressed in this volume.

Q: What is your thought process behind curating these volumes in terms of representation from both LDS and non-LDS scholars, gender, race, academic disciplines, etc?

A: Mormon Studies programing at UVU has always been centered on strong scholarship while also extending our reach to marginalized voices. To date, we have invited guests that span a broad spectrum of Mormon thought and practice. From Orthodox Judaism to Secular Humanists; from LGBTQ to opponents to same-sex marriage; from Feminists to staunch advocates of male hierarchies, all have had a voice in the UVU Mormon Studies Program. Each course, conference, and publication treating these dynamic dialogues in Mormonism are conducted in civility and the scholarly anchors of the academy. Given our disciplinary grounding, our work has expanded the conversation and opened a wide variety of ongoing cooperation between schools of thought that intersect with Mormon thought.

Q: What can readers expect to see coming from the UVU Comparative Mormon Studies series?

A: Our 2019 conference will be centered on the experience of women in and around the Mormon traditions. We have witnessed tremendous scholarship of late in this area and are anxious to assemble key authors and advocates. Other areas we plan to explore include comparative studies in Mormonism and Asian religions, theological approaches to religious diversity, and questions of Mormon identity.

Download a free sample of The Expanded Canon

Listen to an interview with the editors

Upcoming events for The Expanded Canon:

Tue Sep 18 at 7pm | Writ & Vision (Provo) | RSVP on Facebook

Wed Sep 19 at 5:30 pm | Benchmark Books (SLC) | RSVP on Facebook

Q&A Part 1 with the Editors of The Expanded Canon: Perspectives on Mormonism & Sacred Texts August 29 2018

Hardcover $35.95 (ISBN 978-1-58958-637-6)

Part 1: Q&A with Blair G. Van Dyke (Part 2)

Q: How is the Mormon Studies program at Utah Valley University distinguished from Mormon Studies programs that have emerged at other universities?

A: The Mormon Studies program at UVU is distinguished by the comparative components of the work we do. At UVU we cast a broad net across the academy knowing that there are relevant points of exploration at the intersections of Mormonism and the arts, Mormonism and the sciences, Mormonism and literature, Mormonism and economics, Mormonism and feminism, Mormonism and world religions, and so forth. Additionally, the program is distinguished from other Mormon Studies by the academic events that we host. UVU initiated and maintains the most vibrant tradition of creating and hosting relevant and engaging conferences, symposia, and intra-campus events than any other program in the country. Further, a university-wide initiative is in place to engage the community in the work of the academy. Hence, the events held on campus are focused first and foremost for students but inviting the community to enjoy our work is very important. This facilitates understanding and builds bridges between scholars of Mormon Studies and Mormons and non-Mormons outside academic orbits.

Q: Where did the material for The Expanded Canon come from?

A: The material that constitutes volume one of the UVU Comparative Mormon Studies Series came from an annual Mormon Studies Conference that shares the title of the volume. We drew from the work of some of the scholars that presented at that conference to give their work and ours a broader audience. Generally, the contributors to the volume are not household names or prominent authors that regularly publish in the common commercial publishing houses directed at Mormon readership. As such, this volume introduces that audience to prominent personalities in the field of Mormon Studies. It is not uncommon for scholars in this field of study to look for venues where their work can reach a broader readership. This jointly published volume accomplishes that desire in a thoughtful way.

Q: What are a few key points about this volume that would be of interest to readers?

A: Few things are more central to Mormon thought than the way the tradition approaches scripture. And many of their most closely held beliefs fly in the face of general Christianity’s conception of scriptural texts. An open or expanded canon of scripture is one example. Grant Underwood explores Joseph Smith’s revelatory capacities and illustrates that Smith consistently edited his revelations and felt that his revisions were done under the same Spirit by which the initial revelation was received. Hence, the revisions may be situated in the canon with the same gravitas that the original text enjoyed. Claudia Bushman directly addresses the lack of female voices in Mormon scripture. She recommends several key documents crafted by women in the spirit of revelation. Ultimately, she suggests several candidates for inclusion. As the Mormon canon expands it should include female voices. From a non-Mormon perspective, Ann Taves does not embrace a historical explanation of the Book of Mormon or the gold plates. However, she does not deny Joseph Smith as a religious genius and compelling creator of a dynamic mythos. In her chapter she uses Mormon scripture to suggest a way that the golden plates exist, are not historical, but still maintain divine connectivity. David Holland examines the boundaries and intricacies of the Mormon canon. Historically, what are the patterns and intricacies of the expanding canon and what is the inherent logic behind the related processes? Additionally, authors treat the status of the Pearl of Great Price, the historical milieu of the publication of the Book of Mormon, and the place of The Family A Proclamation to the World. These are just a few of the important issues addressed in this volume.

Q: What is your thought process behind curating these volumes in terms of representation from both LDS and non-LDS scholars, gender, race, academic disciplines, etc?

A: Mormon Studies programing at UVU has always been centered on solid scholarship while simultaneously broadening tents of inclusivity. To date, we have invited guests that span spectrums of thought related to Mormonism. From Orthodox Judaism to Secular Humanists; from LGBTQ to opponents to same-sex marriage; from Feminists to staunch advocates of male hierarchies, all have had a voice in the UVU Mormon Studies Program. Each course, conference, and publication treating these dynamic dialogues in Mormonism are conducted in civility and the scholarly anchors of the academy. Given our disciplinary grounding, our work has expanded the conversation and opened a wide variety of ongoing cooperation between schools of thought that intersect with Mormon thought.

Download a free sample of The Expanded Canon

Listen to an interview with the editors

Tue Sep 18 at 7pm | Writ & Vision (Provo) | RSVP on Facebook

Wed Sep 19 at 5:30 pm | Benchmark Books (SLC) | RSVP on Facebook

5 Things to Know Before Studying the Old Testament December 29 2017

Welcome to the study of the Old Testament! Latter-day Saints are about to undertake an exciting journey this year in Gospel Doctrine. The Old Testament is a fascinating book that has had a tremendous influence on the development of LDS scripture and doctrine. As we begin this journey, I have been invited to share some of the main points I would hope readers would keep in mind. For both ancient and modern Judaism, the spiritual foundation of the Hebrew scriptures is the Torah or “Law” (i.e. the opening five books traditionally ascribed to Moses). As a reflection of this tradition, I have chosen five things that I would encourage LDS readers to keep in mind—my own personal “torah,” if you will, for a religious study of the Old Testament.

1. Genesis

The Old Testament contains a variety of distinct literary genres such as law codes, proverbs, satire, erotic poetry, genealogical lists, prophecy, chronicles, and parables (just to name a few). This means that readers of the Bible should not approach a book like Chronicles, for instance, with its emphasis on sources and verisimilitude, in the same way they interpret a book such as Job or Jonah. Without a basic understanding of a text’s specific genre, readers inevitably misinterpret its intended meaning.

For example, in the King James Bible, the book of Job begins with the statement: “There was a man in the land of Uz, whose name was Job” (1:1). Yet this is not the way books typically begin in the Bible. In fact, the uniqueness of the literary construct in Hebrew led one recent scholar to render the verse as, “Once upon a time, in the land of Uz, there was a man named Job.” That opening completely changes the way readers approach the book. Reading the book of Job as a parable or a fable, rather than a historical account, changes the entire way readers relate to the story and poetry of Job. I believe that it is important, therefore, to remember that the Old Testament is not a single book, meant to be interpreted in a single manner. Rather, it is a collection of distinct literary genres from ancient Israel that should not be read as a single volume in the way a person typically reads a novel or history book.

2. Exodus

For example, parts of the Bible relate well to the LDS view concerning the corporeal (bodily) nature of God. Exodus 24:9–11 presents an account where Moses, Aaron, Nadab, Abihu, and seventy elders of Israel ascend Mount Sinai and literally see the “God of Israel” (v. 10). According to that narrative, these men not only saw God’s feet and hand, God literally joined them in eating a communal meal. In this story, God was physical, had a body, and could use it just like a human.

Yet God appears much less physical and human-like in Deuteronomy. Deuteronomy 4:12 tells its readers that when Israel approached the holy mountain, they did not see a God with a body; they only heard a voice: “ye heard the voice of the words, but saw no similitude (tmwnh); only ye heard a voice.” The Hebrew word in this passage translated as “similitude” literally means “form,” and it refers to a physical manifestation. From Deuteronomy’s perspective, God does not have a physical body and no one could see him. Latter-day Saints will therefore find some sections of the Bible to accord with their own theological views and others, perhaps, a little less so.

3. Leviticus

Since the Bible contains a variety of unique and contradictory perspectives written by separate authors over a thousand-year period, I believe that it is best for religious readers to treat the work as a sourcebook rather than a textbook. Like an anthology, a sourcebook presents readers with multiple perspectives. In order to make sense, a textbook typically presents a single specific point of view. Unfortunately, this is the way that most religious readers have traditionally approached the Old Testament.

If, however, a reader approaches the Old Testament in the way that it truly appears (i.e. as a sourcebook presenting multiple perspectives), then the collection can serve as a springboard for enlightenment, helping readers to define their own relationship to divinity. In other words, the Old Testament does not define God. Instead, it defines the way that specific groups of ancient Israelites living in a different time and place understood God.

Adopting this critical approach can help a religious reader when she feels uncomfortable about the way a specific law treats a female rape victim or when a contemporary reader feels uncomfortable with the way God commands the Israelites to completely annihilate the indigenous population of Canaan. If that perspective troubles a reader then the text can serve as a springboard helping him to define his own moral and religious convictions independent from the text.

But readers should also keep in mind that the Old Testament presents contradictory views that will perhaps fall greater in line with the contemporary reader’s own religious convictions. For example, many readers feel troubled by the way the book of Joshua depicts God ordering the destruction of a foreign people without giving them a chance to even repent. Interestingly, that is a view that seems to have also troubled the author of the book of Jonah who constructs a folktale to describe a time where God showed compassion to non-Israelites and gave foreigners a chance to repent, much to the chagrin of the book’s protagonist. The book almost reads as a response to the theology presented in the book of Joshua.

Thus, rather than a manual that perfectly defines God, religion, and morality, the Old Testament should be used as a springboard lifting its readers to further levels of enlightenment as we consider the various ways different groups of Israelite authors understood divinity.

4. Numbers

Unlike the Book of Mormon, the Old Testament was not written for our day. Its writers were not concerned with the far distant future. They were concerned with conditions that affected their own time and people. This can be an especially confusing issue for Latter-day Saint readers since our own unique scriptural texts often adopt and reuse Old Testament material.

A classic illustration of this trend would be the prophecy in Isaiah 29. This text is often presented in LDS scripture as a prophecy concerning Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon. Hence, when LDS readers actually read the chapter in Isaiah they may feel confused trying to fit the entire chapter into their understanding of LDS scripture. Instead, it is helpful to remember that by adopting and transforming sacred writings to fit a new context connected with the Restoration, LDS scripture follows the same trend we see happening in both the New Testament and early Jewish writings.

It is common for later authors to actualize a piece of earlier sacred material into their own time and place, giving the original text a new religious meaning. We see this happening, for example, in the book of Matthew. Matthew presents a total of 14 citations of Old Testament texts that the author links directly with Jesus. He begins with a citation of Isaiah 7:14 concerning a virgin who will conceive a son, and the child’s name will be Emmanuel. However, when that passage is read in its entire context in Isaiah 7 it is clear that Isaiah was not originally referring to Jesus.

The child is specifically presented as a sign to the Judean king Ahaz in order to prove correct Isaiah’s prophecy concerning the kings of Syria and Israel. According to the actual prophecy, before this special child (presumably Hezekiah) reached the age of accountability (i.e. knew how to refuse the evil and choose the good), the land before those two kings would be deserted (v. 16). This was Isaiah’s prediction and the sign he gave to establish its validity.

Jesus, who was born hundreds of years later, could not have fulfilled this specific prophecy. But this does not mean that Matthew got it wrong when he linked the passage with Jesus, anymore than it means that LDS scripture is mistaken to connect Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon with Isaiah 29. This is simply an illustration of a long, venerable tradition in holy writ where a later author recontextualizes an earlier scriptural text to apply to another community or context. To get the most out of these texts, readers should first identify the original Sitz in Leben or “Setting in Life” in which an Old Testament passage appears and then consider the various ways later authoritative works recontextuallize and adopt that passage in order to give the scripture new religious meaning.

5. Deuteronomy

The final point that I would hope readers would keep in mind when studying the Old Testament is to have fun. In fact, many of these stories and traditions were no doubt originally created for that specific purpose. Take for instance the wonderful account in Judges 3 of the fat “Jabba-the-Hutt” like character Eglon who is killed in his outhouse by the left-handed Ehud. Ehud is from the tribe of Benjamin, a tribal designation which means “A Right-Handed Person”—so this makes Ehud a “right-handed left-hander.” The story of Ehud and Eglon’s “filth” that came out of fat belly when he was jabbed in his own outhouse was probably told time and time again around the campfire by Israelite soldiers making fun of their enemies, and now it appears in the book of Judges. These types of stories are indeed fun, and they were meant to make their audience laugh. So enjoy them; laugh with them—be inspired by them.

The Old Testament is a wonderful collection of ancient material with some of the most exciting stories ever told—stories that have had a tremendous effect upon contemporary forms of entertainment from novels to movies. Have fun. Enjoy the process. Learn about biblical poetry. Learn about type scenes and literary genres, prophecy, and proverbs. I believe that making the Old Testament fun can lead readers to serious reflection upon this material. And that reflection can inspire contemporary readers in the same way it did the New Testament authors and the prophet Joseph Smith.

So there you have it. My own personal “torah” for religious study of the Old Testament. I hope it helps and that you enjoy a wonderful year.

David Bokovoy holds a PhD in Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East and an MA in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies both from Brandeis University. David has published articles on the Hebrew Bible in a variety of academic venues including the Journal of Biblical Literature, Vetus Testamentum, Studies in the Bible and Antiquity, and theFARMS Review. He is the co-author of the book Testaments: Links Between the Book of Mormon and the Hebrew Bible and the author of Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis — Deuteronomy as well as the forthcoming Authoring the Old Testament: The Prophets, both part of the Contemporary Studies in Scripture series.

David Bokovoy holds a PhD in Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East and an MA in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies both from Brandeis University. David has published articles on the Hebrew Bible in a variety of academic venues including the Journal of Biblical Literature, Vetus Testamentum, Studies in the Bible and Antiquity, and theFARMS Review. He is the co-author of the book Testaments: Links Between the Book of Mormon and the Hebrew Bible and the author of Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis — Deuteronomy as well as the forthcoming Authoring the Old Testament: The Prophets, both part of the Contemporary Studies in Scripture series.

|

Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis — Deuteronomy Part of the Contemporary Studies in Scripture series “This book should be basic reading for serious LDS students of the Bible.” — Eric D. Huntsman, Coordinator of Ancient Near Eastern Studies, Brigham Young University |

|

Authoring the Old Testament: The Prophets Part of the Contemporary Studies in Scripture series COMING IN 2018 |

Twelve Days of Kofford 2017 November 21 2017

Greg Kofford Books is once again pleased to offer twelve days of discounted holiday shopping from our website!

HERE IS HOW IT WORKS: Every morning from Dec 1th through the 12th, we will be posting a DISCOUNT CODE on our Facebook or Twitter pages. Use this discount code on the corresponding day to receive 30% off select titles. The final day will be an e-book flash sale on Amazon.com.

To help you plan, here are the dates, titles, and sale prices we will be offering beginning Dec 1st. These sales are limited to available inventory. You must follow our Facebook or Twitter pages to get the discount code. Orders over $50 qualify for free shipping. Customers in the Wasatch Front area are welcome to pick orders up directly from our office in Sandy, UT.

Day 1 — Brant Gardner collection

|

Second Witness, Vol 1: First Nephi $39.95 hardcover |

|

Second Witness, Vol 2: Second Nephi through Jacob $39.95 hardcover |

|

Second Witness, Vol 3: Enos through Mosiah $39.95 hardcover |

|

Second Witness, Vol 4: Alma $49.95 hardcover |

|

Second Witness, Vol 5: Helaman through Nephi $39.95 hardcover |

|

Second Witness, Vol 6: Fourth Nephi through Moroni $39.95 hardcover |

|

The Gift and the Power: Translating the Book of Mormon $34.95 paperback |

|

Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History $34.95 paperback |

|

The Garden of Enid: Adventures of a Weird Mormon Girl $22.95 paperback |

|

The Garden of Enid: Adventures of a Weird Mormon Girl $22.95 paperback |

Day 3 — The Mormon Image in Literature

|

The Mormoness; Or, The Trials of Mary Maverick: $12.95 paperback |

|

Boadicea; the Mormon Wife: Life Scens in Utah $15.95 paperback |

|

Dime Novel Mormons $22.95 paperback |

|

Women at Church: Magnifying LDS Women's Local Impact $21.95 paperback |

|

Mormon Women Have Their Say: Essays from the Claremont Oral History Collection $31.95 paperback |

|

Voices for Equality: Ordain Women and Resurgent Mormon Feminism $32.95 paperback |

|

Joseph Smith's Polygamy, Vol 1: History $34.95 paperback |

|

Joseph Smith's Polygamy, Vol 2: History $34.95 paperback |

|

Joseph Smith's Polygamy, Vol 3: Theology $25.95 paperback |

|

Joseph Smith's Polygamy: Toward a Better Understanding $19.95 paperback |

|

Modern Polygamy and Mormon Fundamentalism: The Generations after the Manifesto $31.95 paperback |

|

Mormon Polygamous Families: Life in the Principle $24.95 paperback |

|

Prisoner for Polygamy: The Memoirs and Letters of Rudger Clawson at the Utah Territorial Penitentiary, 1884–87 $29.95 paperback |

|

Who Are the Children of Lehi? DNA and the Book of Mormon $15.95 paperback |

|

“Let the Earth Bring Forth”: Evolution and Scripture $15.95 paperback |

|

Mormonism and Evolution: The Authoritative LDS Statements $15.95 paperback |

|

Parallels and Convergences: Mormon Thought and Engineering Vision $24.95 paperback |

|

Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life $32.95 hardcover |

|

“Swell Suffering”: A Biography of Maurine Whipple $31.95 paperback |

|

William B. Smith: In the Shadow of a Prophet $39.95 paperback |

|

LDS Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 Vols $259.95 paperback |

|

The Man Behind the Discourse: A Biography of King Follett $29.95 paperback |

|

Liberal Soul: Applying the Gospel of Jesus Christ in Politics $22.95 paperback |

|

A Different God? Mitt Romney, the Religious Right, and the Mormon Question $24.95 paperback |

|

Common Ground—Different Opinions: Latter-day Saints and Contemporary Issues $31.95 paperback |

|

Even Unto Bloodshed: An LDS Perspective on War $29.95 paperback |

|

War & Peace in Our Time: Mormon Perspectives $29.95 paperback |

|

The End of the World, Plan B: A Guide for the Future $13.95 paperback |

|

Dead Wood and Rushing Water: Essays on Mormon Faith, Culture, and Family $22.95 paperback |

|

Mr. Mustard Plaster and Other Mormon Essays $20.95 paperback |

|

Writing Ourselves: Essays on Creativity, Craft, and Mormonism $18.95 paperback |

|

On the Road with Joseph Smith: An Author's Diary $14.95 paperback |

|

Hearken O Ye People: The Historical Setting of Joseph Smith's Ohio Revelations $34.95 hardcover |

|

Fire and Sword: A History of the Latter-day Saints in Northern Missouri, 1836–39 $36.95 hardcover |

|

A House for the Most High: The Story of the Original Nauvoo Temple $29.95 paperback |

|

Villages on Wheels: A Social History of the Gathering to Zion $24.95 paperback |

|

Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890–1930, 3rd ed. $31.95 paperback |

Day 11 — International Mormonism

|

Tiki and Temple: The Mormon Mission in New Zealans, 1854–1958 $29.95 paperback |

|

Mormon and Maori $24.95 paperback |

|

The Trek East: Mormonism Meets Japan, 1901–1968 $39.95 paperback |

|

From Above and Below: The Mormon Embrace of Revolution, 1840–1940 $34.95 paperback |

|

The History of the Mormons in Argentina $24.95 paperback |

|

For the Cause of Righteousness: A Global History of Blacks and Mormonism, 1830–2013 $32.95 paperback |

Author Spotlight: David Bokovoy November 15 2017

David Bokovoy, author of Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis—Deuteronomy, part of the Contemporary Studies in Scripture series.

Can you give us a little background into your education and how you became interested in religious studies/biblical criticism?

I majored in History and minored in Near Eastern studies at BYU. I did my graduate work at Brandeis University, a non-sectarian Jewish institution. I received my MA in Jewish Studies and my PhD in Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East. I’m currently the online professor in Bible and Jewish studies at Utah State University.

I developed a passion for the study of Mormon history, doctrine, and theology in my late teenage years. This passion continued to develop during my two-year mission for the LDS Church in Brazil. As hard as it was, I would try to wake up an hour early to read the material I wanted, but that weren’t part of the official Mormon Missionary library—things like Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, Discourses of Brigham Young, the Great Apostasy, and Doctrines of Salvation. I thought that if I was willing to sacrifice my sleep to read this unofficial material, I could justify breaking the rules a bit. Other than that, I was a very obedient missionary.

I loved my mission, but I longed for the days when I could devote hour after hour to serious Gospel study. When I returned home, I took an LDS Institute class from a teacher who knew a little bit of Hebrew. I knew right away that I had to learn that language to improve my understanding of the scriptures. That study eventually led to the pursuit of graduate work in the field of historical criticism and the Bible.

How can biblical criticism compliment faith?

I have come to believe that a critical approach to scripture is, in fact, an essential part of a spiritual journey. Historical criticism is an effort to read religious texts in their original historical context, independent from one’s own religious tradition. This allows religious readers to understand the way that people from different time periods and cultures understood divinity. Religious paradigms exist in a perpetual state of flux. So, the way we understand God today is not the same way that people in the ancient world understood God. Learning to see and appreciate their approach can provide a religious reader with new ways of appreciating the divine.

Despite its religious merits, scripture should not be seen as an infallible manual to divinity. Instead, scripture is the textual result of a human effort to reflect the divine. Though inevitably flawed by mortal hands, scripture can inspire meaningful spiritual growth. This is true even when a reader encounters a construct in holy writ that she rejects, since that problematic paradigm has caused the reader to define her own spiritual conviction in opposition to the one held by the author. I believe that scripture is not a manual; it is a springboard. And I believe that historical critical analysis can help lift a reader to higher levels of enlightenment. Like Joseph Smith, I believe that Mormonism is a religion that seeks to embrace all truth, let it come from whatever source it may, including historical criticism.

What are you hoping readers will gain from reading your first volume of Authoring the Old Testament?

The first volume was a highly personal work. I had been told by a couple of my BYU professors not to pursue degrees in biblical studies because we had not ever had an LDS person pass through such a program and retain his or her testimony. I wanted to share with an LDS audience how I make sense of my faith in light of my passion for critical biblical scholarship. I wanted to show that one could be a faithful Mormon and a critical scholar.

Can you give us a sneak peek into some of the themes you’ll be exploring in the next volume?

In volume two of the series, I will introduce LDS readers to a critical reading of the prophetic books of the Bible. I hope to show how a critical historical approach to this material can help religious readers make sense of complicated works like the book of Isaiah.

Thanks, David!

Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis—Deuteronomy

Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis—Deuteronomy

by David Bokovoy

Part of the Contemporary Studies in Scripture series

“Members of the Church will be introduced to some of the results of over a century of biblical scholarship they’ve likely never heard about.”

— Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship

Also check out David Bokovoy's chapter contribution to Perspectives on Mormon Theology: Apologetics.