News

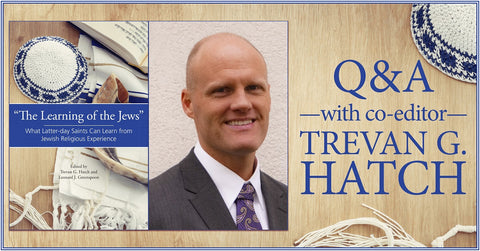

Q&A with Trevan G. Hatch, co-editor of "The Learning of the Jews": What Latter-day Saints Can Learn from Jewish Religious Experience August 03 2021

Q: Can you provide a little background about the editors and your decision to do this project together?

A: I participated with Leonard Greenspoon in several Jewish Studies seminars in Chicago from 2012 to 2018. In 2016 I approached him about getting Jewish scholars and LDS scholars together for this writing project. As a prolific scholar in Bible and Jewish Studies for forty years, Leonard has participated in these types of interfaith interactions many times, but never with Latter-day Saints. Leonard and I then contacted several scholars to participate. Many of the Jewish scholars were excited to write essays due to the unique nature of the project.

Q: What makes this book unique among interfaith dialogues?

A: Traditional interfaith dialogues are very common. So why do I call this project “unique”? Customarily, the purpose of interfaith dialogue is for two groups to come together and discuss commonalities. The “Kumbaya” nature of these interfaith dialogues serve to foster understanding and empathy. This project is unique because we did NOT want to follow the typical style of each group learning from each other. In other words, we did not want to tell Jews that Latter-day Saints want to learn from them, but that they must learn from Latter-day Saints as well. Christians have forced Jews for 1,500 years to learn about Christianity (or even convert to Christianity). In this volume, we sought to give Jews “the microphone” so-to-speak and let them talk about their own experience without imposing an agenda on them. Our intent was to discuss and examine Judaism on Jewish terms (as best we can) and subsequently wrestle with how Latter-day Saints might benefit from 3,000 years of the Jewish experience. Our purpose is not to suggest that Latter-day Saints must adopt various Jewish practices and beliefs. Rather, we hoped that the discussions in this volume may assist readers in adopting strategies, mentalities, and approaches to religious and cultural living as exemplified by Jews and Judaism. The chapters are meant to serve as catalysts for further introspection and learning, not as the end-all-be-all for how Latter-day Saints might learn from Jewish religious experience.

Q: How is this book organized?

A: This volume brings together fifteen scholars, seven Jewish and eight Latter-day Saint, with a combined academic experience of over four hundred years. We have structured the volume around seven major topics, two chapters on each topic. A Jewish scholar first discusses the topic broadly vis-à-vis Judaism, followed by a response from a Latter-day Saint scholar. These Latter-day Saint scholars are trained in various fields of study and disciplines including history, sociology, family studies, religious studies, biblical studies, and literature. This wide array of experience and training illustrates the various approaches and perspectives of learning from another group. With the primary purpose of this volume being for Latter-day Saints to learn from Jewish religious perspectives and experiences, the essays are generally different from what you might expect in an interreligious dialogue. For the most part, the Jewish essays were not written with Latter-day Saints in mind but are simply broad overviews that could be helpful for any non-Jewish readership. Likewise, the Latter-day Saint responses are not trying to find commonalities as the primary goal; rather, their purpose is to explore any strategies, mentalities, motives, etc., of Jews that might serve as a catalyst for Latter-day Saints to look introspectively and enhance their own lived religious experience.

Q: Can you highlight some of the main topics discussed in the book?

A: The seven topics include scripture, authority, prayer, women and modernity, remembrance, particularity, and humor. Most of these topics are salient in Jewish discourse today. It so happens that Latter-day Saints focus on several of these topics with a great amount of zeal, especially scripture, authority, prayer, and women & modernity.

Q: What are you hoping that readers will take away from this book?

A: We hope that the reader will not only learn a great deal about Judaism and the Jewish experience while reading this volume, but also use what they learn to enhance their own cultural and religious experience.

Trevan Hatch, August 2021

Q&A Part 2 with the Editors of The Expanded Canon: Perspectives on Mormonism & Sacred Texts September 11 2018

Hardcover $35.95 (ISBN 978-1-58958-637-6)

Part 2: Q&A with Brian D. Birch (Part 1)

Q: When and how did the Mormon Studies program at UVU launch?

A: The UVU Mormon Studies Program began in 2000 with the arrival of Eugene England. Gene received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to explore how Mormon Studies could succeed at a state university. A year-long seminar resulted that included a stellar lineup of consultants and guest scholars. From that point forward, the Religious Studies Program has developed multiple courses complemented by our annual Mormon Studies Conference and Eugene England Lecture—to honor Gene’s tragic and untimely passing in 2001. The program also hosts and facilitates events for independent organizations and publications including the Society for Mormon Philosophy and Theology, the Dialogue Foundation, the Interpreter Foundation, Mormon Scholars in the Humanities, Association for Mormon Letters, and others.

Q: How is the UVU Mormon Studies program distinguished from Mormon Studies programs that have emerged at other campuses?

A: Mormon Studies at UVU is distinguished by the explicitly comparative focus of our work. Given the strengths of our faculty, we have emphasized courses and programming that addresses engagement and dialogue across cultures, faith traditions, and theological perspectives. Permanent course offerings include Mormon Cultural Studies, Mormon Theology and the Christian Tradition, Mormon Anthropology, and Mormon Literature. Our strengths lie in areas other than Mormon history, which is well represented at other institutions—and appropriately so. Given the nature of our institution, our events are focused first and foremost on student learning, but all our events are free and open to the public and we welcome conversation between scholars and nonprofessionals.

Q: How long has the annual UVU Mormon Studies Conference been held, and what have been some of the topics of past conferences?

A: As mentioned above, the Mormon Studies Conference was first convened by Eugene England in 2000, and to date we have convened a total of nineteen conferences. Topics have ranged across a variety of issues including “Islam and Mormonism,” “Mormonism in the Public Mind,” “Mormonism and the Art of Boundary Maintenance,” “Mormonism and the Internet,” etc. We have been fortunate to host superb scholars and to bring them into conversation with each other and the broader public.

Q: Where did the material for the first volume, The Expanded Canon, come from?

A: The material in The Expanded Canon emerged came from our 2013 Mormon Studies Conference that shares the title of the volume. We drew from the work of conference presenters and added select essays to round out the collection. The volume is expressive of our broader approach to bring diverse scholars into conversation and to show a variety of perspectives and methodologies.

Q: What are a few key points about this volume that would be of interest to readers?

A: Few things are more central to Mormon thought than the way the tradition approaches scripture. And many of their most closely held beliefs fly in the face of general Christianity’s conception of scriptural texts. An open or expanded canon of scripture is one example. Grant Underwood explores Joseph Smith’s revelatory capacities and illustrates that Smith consistently edited his revelations and felt that his revisions were done under the same Spirit by which the initial revelation was received. Hence, the revisions may be situated in the canon with the same gravitas that the original text enjoyed. Claudia Bushman directly addresses the lack of female voices in Mormon scripture. She recommends several key documents crafted by women in the spirit of revelation. Ultimately, she suggests several candidates for inclusion. As the Mormon canon expands it should include female voices. From a non-Mormon perspective, Ann Taves does not embrace a historical explanation of the Book of Mormon or the gold plates. However, she does not deny Joseph Smith as a religious genius and compelling creator of a dynamic mythos. In her chapter she uses Mormon scripture to suggest a way that the golden plates exist, are not historical, but still maintain divine connectivity. David Holland examines the boundaries and intricacies of the Mormon canon. Historically, what are the patterns and intricacies of the expanding canon and what is the inherent logic behind the related processes? Additionally, authors treat the status of the Pearl of Great Price, the historical milieu of the publication of the Book of Mormon, and the place of The Family: A Proclamation to the World. These are just a few of the important issues addressed in this volume.

Q: What is your thought process behind curating these volumes in terms of representation from both LDS and non-LDS scholars, gender, race, academic disciplines, etc?

A: Mormon Studies programing at UVU has always been centered on strong scholarship while also extending our reach to marginalized voices. To date, we have invited guests that span a broad spectrum of Mormon thought and practice. From Orthodox Judaism to Secular Humanists; from LGBTQ to opponents to same-sex marriage; from Feminists to staunch advocates of male hierarchies, all have had a voice in the UVU Mormon Studies Program. Each course, conference, and publication treating these dynamic dialogues in Mormonism are conducted in civility and the scholarly anchors of the academy. Given our disciplinary grounding, our work has expanded the conversation and opened a wide variety of ongoing cooperation between schools of thought that intersect with Mormon thought.

Q: What can readers expect to see coming from the UVU Comparative Mormon Studies series?

A: Our 2019 conference will be centered on the experience of women in and around the Mormon traditions. We have witnessed tremendous scholarship of late in this area and are anxious to assemble key authors and advocates. Other areas we plan to explore include comparative studies in Mormonism and Asian religions, theological approaches to religious diversity, and questions of Mormon identity.

Download a free sample of The Expanded Canon

Listen to an interview with the editors

Upcoming events for The Expanded Canon:

Tue Sep 18 at 7pm | Writ & Vision (Provo) | RSVP on Facebook

Wed Sep 19 at 5:30 pm | Benchmark Books (SLC) | RSVP on Facebook

Contesting Truth through Mutual Openness July 18 2018

Charles Randall Paul will be speaking on the topic of religious diplomacy and signing copies of his book at Weller Book Works (Salt Lake City) on Tuesday, Aug. 7th at 6:30 PM and at Writ & Vision (Provo) on Thursday, Aug. 9th at 7PM. Both events are free to attend.

Humans are social influencers by their very existence. They are always intentionally persuading each other in some fashion. All human life includes continual negotiation of social activities from “pass the salt” to “should we get married?” When one of us believes a purpose is good and an action right, that influences a response from others—and the response influences further responses.

While the ideal might be complete social unity or unconstrained freedom for all, human groups and societies should expect continual religious and ideological contestation. Within our interconnected societies, conflicting world-views and purposes are inevitable. No social program for peace will succeed that requires adamant believers to compromise or dilute their core values. Instead, we sustain peaceful tension within our societies through co-resistance and collaboration with our ideological rivals. Crucial to this is the absence of ill-will in our collaborative contestation.

Let me now make a distinction between these terms: Enemy, antagonist, agonist, ally, and friend. An enemy desires and acts to eliminate, enslave, or diminish others by passive or aggressive means. An antagonist acts like an enemy but does not desire to be one. If she presumes you are an enemy, she might be reacting defensively with no intent to harm you otherwise. An agonist is a fellow contestant who desires to win an ideological contest through persuasion. An ally is on your side because of shared interests. A friend desires your love and well-being and will self-sacrifice to promote it. It is possible to be an ally that is also really an enemy, but it is impossible to be a real friend and an enemy. However, your agonistic rival can also be your friend—but enduring (much less enjoying) this relationship is an acquired taste and skill.

If you have a real enemy, you need to defend yourself accordingly. But we need to determine first if antagonists are true enemies or agonists. An agonist desires to contest differences in order to bring about positive change for both sides, rather than the destruction of their rival. Sportsmanship is a common attitude of agonists. Persuading agonists to your side may make them allies; but converting agonists to trust and love can make them friends even while they remain persuasive agonists. The path forward lies in vulnerable openness between rivals with an open and honest disclosure of motives and beliefs. This requires courage to exchange critical and offensive ideas and ideals without taking offense. Let there be no mistake: openness that is truly open to change is always a dangerous experiment, especially for those who are concerned about diluting true orthodoxy (on the left or right) with relativism.

To prepare for inevitable contestations over religious, political, or ideological differences, I present ten useful attitudes and methods to remember when the pressure to either disengage or eliminate our fellow agonists becomes intense. I call this The Way of Mutual Openness:

Be Honest

Honesty begins when you look in the mirror. Who do you really think you are and who do want to become? When you are deeply honest, you acknowledge your motives for doing things and express your thoughts and feelings without faking it. Your honesty prompts others to respond the same way, and with open hearts and minds real communication results.

Be Kind

Kindness goes further toward building trust than the other practices listed here. It is not weak, naive, or mere politeness. Kindness is a language easily recognized and understood by everyone. Sincere kindness is a powerful way to influence others to desire to hear you. But, be wise: nothing shatters trust more than phony, manipulative kindness, or false respectfulness.

Listen Well

It is hard to listen well when you focus more on your feelings and thoughts than those of the person addressing you. Listening well is not remaining quiet before you insert your response; it is intense focus on a unique person with a desire for understanding. By listening like this to others you offer the gift of respectful empathy that everyone craves to receive. In return others feel like they should listen well to understand you.

Share the Floor

If you want to be taken seriously you must take others seriously. Sharing the floor means allowing others equal time to speak even when you “know” you are right and they are wrong. It acknowledges the mutual dignity of those engaged in conversation. Hogging the floor is disrespectful and rude, and it always undermines your persuasive ability when you appear dismissive or fearful of what others have to say.

Presume Good Will

We often presume that others do not have our best interests at heart. Sometimes they don’t. But you sabotage any honest communication with someone you presume to be stupid, duped, or ill-intentioned. Presuming good will is not agreeing with others’ beliefs or values. It means that you grant that others are clear thinking and good hearted unless they prove otherwise.

Acknowledge the Differences

Each human is uniquely different with a unique history and perspective. Acknowledging our important differences openly frees us to know where we stand without having to guess. It creates a tone of trust for real conversation. You cannot feel whole or honest if you focus only on similarities and avoid facing differences in deep beliefs and values.

Answer the Tough Questions

With genuine differences come tough questions—especially if the goal is a trusting relationship. When you answer tough questions in a straightforward way, sharing the floor equally and presuming good will, you build strong mutual trust. You can then face offensive issues without taking offense. However, diving deeper for better understanding has a limit. Aggressive interrogation or pushing for private details destroys trust.

Give Credit Where Credit is Due

Any compliment feels good, but a sincere compliment from an unexpected source such as a rival or critic can move our hearts powerfully toward trust. By openly admiring the excellence or good on “the other side” you demonstrate your honesty and fairness, and your confidence that your side can handle the truth. But be cautious—insincere compliments to manipulate or disarm others disastrously undermine any grounds for trust.

Speak Only for Yourself

Each of us is unique and we don’t like others—especially outsiders—to stereotype us or claim they know what we really believe or value. So, ask rather than tell others what they think and feel. It is tempting to speak for your friends and tribe members as if they all share the same view as you do. Except when you have been authorized to speak on behalf of others, speak only for yourself and encourage others to do likewise.

Keep Private Things Private

Humans are social beings, but their thoughts and feelings are private unless expressed. Personal dignity is based in large part on your freedom to choose when and where to share your inner self with others. Being open, honest, and trustworthy does not require you to disclose all things to all people. Keeping private things private means that you strictly honor someone’s choice to say something to you alone. If you cannot keep it private, you should ask the person not to share it.

These are the times that try our souls. In our increasingly polarized society, we will doubtless continue arguing over political, ideological, and religious differences. Based on years of experience in religious diplomacy, I believe the ten attitudes above will sustain with confidence anyone using them to actively engage in challenging and rewarding conversations that build healthy trust.

Charles Randall Paul is board chair, founder, and president of the Foundation for Religious Diplomacy. He has lectured widely and written numerous articles on healthy methods for engaging differences in religions and ideologies. He is the author of Converting the Saints: A Study of Religious Rivalry in America.

Charles Randall Paul is board chair, founder, and president of the Foundation for Religious Diplomacy. He has lectured widely and written numerous articles on healthy methods for engaging differences in religions and ideologies. He is the author of Converting the Saints: A Study of Religious Rivalry in America.

Q&A with Charles Randall Paul for Converting the Saints: A Study of Religious Rivalry in America July 06 2018

Hardcover $49.99 (ISBN 978-1-58958-747-2)

Available August 7, 2018

Pre-order Your Copy Today

Q: Give us some insight into your background, how you chose to write about this topic, and your involvement with religious diplomacy.

A: I was raised in northern New Jersey where my high school of 400 kids consisted of three major cliques: Jewish, Roman Catholic and Mainline Protestant. There were four Mormons. I was surprised to find how solid and happy my friends’ families were. How could they be so good without The Truth? In mid life I became interested in how religious and secular societies faced unresolvable conflicts over truth and authority and right values. It seemed God had set up the world for pluralistic contestation, and I tried to figure out why. These issues led me to develop interreligious diplomacy as a mode of interaction that included persuasive contestation between trustworthy advocates.

Q: Tell us briefly about the three case studies in this book. Who are these individuals and how did they differ in their tactics from one another?

A: In the early twentieth century after Utah had been accepted as a state, the major Protestant churches wanted to assure that Mormonism was not accepted as another Christian denomination. John Nutting, a freelance pastor, evangelical/preacher came to Utah with young college age missionaries to save souls that, after hearing his revival teaching or door-to-door witnessing, simply confessed the true Jesus and stopped attending the Mormon church. William Paden, a Presbyterian, educator/activist, helped set up 1–12 grade schools that taught LDS students “true” Christianity along with math and English. He also tried to discredit the LDS leadership, close down the Mormon Church, and educate its youth in the right way. Franklin Spaulding was an Episcopal Bishop intellectual/diplomat that aimed to educate LDS college students in the inconsistences of some of the Mormon Church claims. He hoped to convert the Saints in their pews—urging church leaders that he befriended to change just a few doctrines and join the mainline churches.

Q: You state that ongoing debate between religious ideology is at the heart of what it means to be a pluralistic society. Can you elaborate on this?

A: Humans in societies live by stories that order their lives. Ideological or religious traditions provide the comprehensive order and hope for a better world. These religious stories can seriously challenge the veracity of their rival claimants to truth and authority—making for conflict. Contemporary social conflict theorists have focused almost exclusively on conflicting economic and security interests as the engines for conflict, neglecting the cultural driver that religious tradition provides. I am bringing into focus the potency of conflicting formational stories in any society.

Q: Why isn’t tolerance always the desired outcome? How can two opposing people or groups find meaningful ways of collaboration?

A: Tolerance is a weak social virtue (devoid of trust or good will) that collapses when economic and security crises lead societies to seek for scapegoats. We have found that ideological opponents who engage honestly by means of persuasion actually can come to trust and “enjoy” each other’s bothersome presence. People engage in collaborative co-resistance n many forms—sports being the most obvious—legal, legislative, scientific and commercial realms also absorb non-violent conflict managing procedures. When religion is involved, there is no room for compromise solutions, so some form of sustaining the ideological contest in a mode of persuasion is needed. This is healthy intolerance because it allows critics and rivals to be authentic and to have conversations that matter.

Q: For Latter-day Saints, contention is a particularly discomforting word. In your book, you say that you prefer the term “contestation.” Can you explain what you mean?

A: This is a key to understanding how the LDS can lead in the goal of peace-building in split families or societies. We rightly learn that Jesus and Joseph thought contention—a term based on a root of forcing, twisting, coercing others—was the devil’s work. It includes anger and contempt and resentment and revenge. On the other hand, those who stand for something as witnesses need to elevate the term contestation that means to witness with, for or against something—the root being the testimony of a witness. The design of heaven and Earth seems to include many intelligences with different experiences to which they can respectfully testify without fear or anger. They have different viewpoints and experiences that bring them to conflicting contestants; honestly speaking the truth they see. This is what the Holy Spirit prompts us to do. It is the opposite of contentiousness even though the conflict of interpretation and ultimate concern or story remains. Peaceful tension results from contestation—and that is enough for Zion to thrive. Oneness cannot be identical interpretation and understanding of everything that would make individual existence redundant.

Q: We live in an age of intense ideological polarization. What are you hoping that readers will learn from the case-studies presented in this book?

A: I want them to read the book in the broad context of the problem of pluralism that began, narratively speaking, when Eve was different than Adam. I trace the American system of managing religious conflict as a living aspect of society. As long as it remains in the persuasive mode, it allows free expression in the balancing of ideological drives for hegemony. America is based on a foundation of continually contested foundations. Our culture can thrive on pluralism, not because we follow laws of procedural conflict management, but because we have a deep belief in the value of a worthy rival in religion as well as any other aspect of life. The case studies I show will hopefully move a reader to understand how the desire for a trustworthy opponent is a precious thing that does not come naturally but is essential to the success of a pluralistic society.