News

Newell G. Bringhurst Speaking Events April 13 2018

| Date & Time | Location |

| Tue April 24 at 5:30 PM | Benchmark Books, SLC |

| Thur April 26 at 7:00 PM | Writ & Vision, Provo |

| Fri April 27 at 5:00 PM | Main Street Books, Cedar City |

| Sat April 28 at 4:00 PM | Home of Doug Bowen, St. George |

NOW AVAILABLE

“An excellent treatment of an important part of American religious life. Bringhurst succeeds in showing the Mormons as a microcosm of the American population.” — The American Historical Review

“In many regards Bringhurst established the terms on which subsequent scholars would engage race and Mormonism” — W. Paul Reeve, author of Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness

Sign up for our newsletter to stay informed

about future events and book releases

Five Times Mormons Changed Their Position on Slavery March 28 2018

Mormonism and Black Slavery:

Changing Attitudes and Related Practices, 1830–1865

By Newell G. Bringhurst

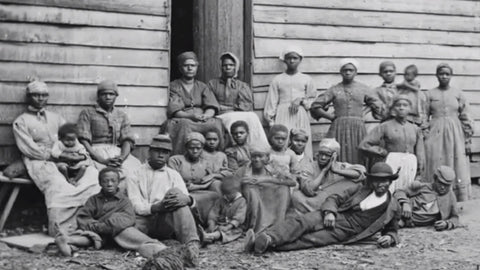

Mormon attitudes and practices relative to black slavery shifted over the course of the first thirty-five years of the Latter-day Saint movement, evolving through five distinct phases.

Phase 1 – Opposition to Slavery in the Book of Mormon

Initially Joseph Smith expressed strong opposition to slavery through the pages of the Book of Mormon. While not specifically referring to black people, Mormonism’s foundational work asserted that “it was against [Nephite] law” to enslave those less favored than themselves, namely the dark Lamanites (Alma 27:9; Mosiah 2:13). In fact, the idolatrous Lamanites were the ones who practiced slavery, making repeated efforts to enslave the light-skinned, chosen Nephites. Lamanite slaveholding was cited as proof of this people’s “ferocious and wicked nature” (Alma 50:22). Nephite resistance to the Lamanites was described as a struggle for freedom from bondage and slavery.

Phase 2 –Detachment towards Slavery in Ohio and Missouri

Mormon attitudes toward slavery entered a second phase of deliberate detachment following the formal organization of the Church in 1830. Through the pages of the Church’s official newspaper, the Evening and Morning Star, Joseph Smith and others avoided discussion of this increasingly controversial topic. No mention was made of Book of Mormon verses condemning slavery. A major reason for such deliberate detachment was the establishment of Mormonism’s Zion in Missouri, a slave state. Church officials sought to disassociate themselves from the fledgling Abolitionist movement.

Despite this, the Church found itself compelled to speak out on the issue on two important occasions. The first involved Joseph Smith’s “Revelation and Prophecy on War” brought forth on 25 December 1832 and ultimately canonized as Section 87 in the Doctrine and Covenants. In this apocalyptic document, Smith prophesized that “wars…will shortly come to pass, beginning at the rebellion of South Carolina [and]…poured out on all nations” (D&C 87:1–2). It further declared that the “slaves will rise up against their masters, who shall be marshalled and disciplined for war” (D&C 87:4). Given its explosive implications, this revelation was not disclosed to the general Church membership until two decades later.

By contrast, a second Mormon statement, “Free People of Color” written by W. W. Phelps and published in the July 1833 issue of the Evening and Morning Star, received immediate exposure resulting in dire consequences. Prompting Phelps’s statement was a dramatic four-fold increase in the number of Mormons settling in Jackson County. The article’s stated purpose was “to prevent any misunderstanding . . . respecting free people of color, who may think of coming to . . . Missouri as members of the Church.”[1] However, it had the opposite effect, angering local non-Mormons who expelled the Latter-day Saints from Jackson County.

Phase 3 – Pro-slavery Sympathies in Missouri

By the mid 1830s, Church attitudes toward slavery shifted yet a third time, Church spokesmen affirming support for slavery. In August 1835, the Church issued an official declaration stating that it was not “right to interfere with bond-servants, nor baptize them contrary to the will and wish of their masters” nor cause “them to be dissatisfied with their situations in this life.” Ultimately this statement was incorporated into the Doctrine and Covenants as Section 134. Eight months later, in April 1836, Joseph Smith reaffirmed Mormon pro-slavery sympathies through a lengthy discourse published in the official Latter-day Saints Messenger and Advocate. Smith raised the specter of “racial miscegenation and possible race war” if abolitionism prevailed.[2] He further stated that the people of the North have no “more right to say that the South shall not hold slaves, than the South have to say the North shall.”[3] He referenced the Old Testament, specifically the “decree of Jehovah” that blacks were cursed with servitude.[4] Other church spokesmen echoed Smith’s sentiments, in particular Oliver Cowdery and Warren Parrish. This Mormon shift reflected an increased Mormon presence in the slave state of Missouri during the late 1830s, along with a desire to carry the Mormon message to potential converts in the slaveholding South. But most importantly, it represented strong Mormon reaction against the establishment of a chapter of the American Anti-slavery society in the Mormon community of Kirtland Ohio.

Phase 4 – Anti-slavery Position in Nauvoo

By the early 1840s Smith and his followers shifted their position yet a fourth time, assuming a strong anti-slavery position, most evident during the Mormon leader’s 1844 campaign for U.S. president. In his “Views on the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States” Smith advocated the abolition of slavery through gradual emancipation and colonization of the freed blacks abroad.[5] He called for the “break down [of] slavery” and removal of “the shackles from the poor black man” through a program of compensated emancipation financed through the sale of public lands.[6] Smith predicted that his proposal could eliminate slavery by 1850. Motivating this changing position were two major factors: one was the Mormon’s forced expulsion from the slave state of Missouri in 1838-39. The second involved demographics, namely the fact that the majority of church members hailed from non-slaveholding regions north of the Mason-Dixon line and from Great Britain. By contrast, a relatively limited number of new converts were drawn from the slaveholding South.

Phase 5 – Pro-slavery Position in Utah Territory

Mormon attitudes and related practices relative to slavery shifted yet a fifth and final time following the death of Joseph Smith in 1844 with the emergence of Brigham Young as the principal leader of the Latter-day Saints who migrated west. Young’s evolving position represented “a bundle of contradictions.”[7] Initially, he advocated a “free soil”[8] stance in a June, 1851, sermon, rhetorically stating, “shall we lay a foundation for Negro slavery? No, God forbid!”[9] Six months later in the wake of his appointment as Utah Territorial Governor, Young retreated from this position. Despite his assertion that “my own feelings are that no property can or should exist in slaves,” Young called on the territorial legislature adopt a form of benevolent indentured servitude to regulate Utah’s small but visible black population.[10] Two weeks later, addressing that same body, he proclaimed himself “a firm believer in slavery,”[11] urging legalization of the Peculiar Institution.[12] On February 4, 1952, the Utah Territorial Legislature passed “An Act in Relation to Service” which Young signed into law, making Utah the only Western territory to allow black slavery. Justifying his action, Young delivered a lengthy discourse in which he promoted a direct link between black slavery and black priesthood denial—the latter practice which he announced publicly for the first time. He further asserted that the two proscriptions were both intertwined and divinely sanctioned.

Four factors prompted Young to promote “An Act in Relation to Service.” First, the measure represented a response to the presence of sixty to seventy black slaves in the territory belonging to twelve Mormon slave owners. Among the most prominent were Apostle Charles C. Rich, William H. Hooper (an important Mormon merchant who served as Utah’s Territorial delegate to Congress), and Abraham O. Smoot, Salt Lake City’s first mayor. Second, Young hoped to secure southern support for Utah statehood. Young noted that there were “many [brethren] in the South with a great amount [invested] in slaves” who might migrate to the Great Basin if their slavery property were protected by law.[13]

Of crucial importance in motivating the Mormon leader was a third factor: his strong, unyielding belief that blacks were inherently inferior to whites in all respects and thus naturally fit for involuntary servitude. He accepted, uncritically, the traditional biblical genealogy that present-day Africans came through the so-called accursed lineage of Canaan and Ham back to Cain, thereby providing divine sanction to their servile condition. Further legitimizing black inferiority was the denial of priesthood ordination to black males, which Young affirmed as “a true eternal [principle] the Lord Almighty has ordained.” He stated: “If there never was a prophet or apostle of Jesus Christ spoke it before, I tell you, this people that are commonly called negroes are the children of old Cain, I know they are, I know that they cannot bear rule in the priesthood.”[14]

A fourth, seemingly counterintuitive factor activated Young: his desire to discourage slaveholding in the territory. A careful reading of the statute’s provisions indicates that it consisted primarily of rules to control and restrict slaveholders, and only, incidentally, proscriptions on black slaves themselves. For example, the act required Utah slaveholders to prove that servile blacks had entered the territory “of their own free will and choice.”[15] It also stated that slaveholders could not sell their slaves or remove them from the territory without the so-called servants explicit consent. In general, “An Act in Relation to Service” contrasted sharply with Southern slaveholding statutes in that it was more akin to the practice of indentured servitude. Later that same year, Young reflected on the act’s impact, claiming that it had “nearly freed the territory of the colored population.”[16] Ultimately, Utah Territorial slavery was completely outlawed through a federal statute enacted in 1862, affecting not just the Mormon-dominated region but all other federal territories as well.

Conclusion

The LDS Church’s ever shifting encounter with the institution of black slavery during the thirty-five years from 1830 to 1865 represents a complex, often contradictory odyssey. This perplexing journey profoundly affected Mormonism’s relationship with black people in general. While the number of blacks that Latter-day Saints actually held in bondage was miniscule, the fact that Brigham Young sanctioned the practice of black slavery in conjunction with his imposition of black priesthood and temple denial underscores slavery’s seminal impact on the now-defunct proscription on black people—such practice viewed as Church doctrine for over one hundred and twenty-five years.

Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People Within Mormonism, 2nd ed.

Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People Within Mormonism, 2nd ed.

By Newell G. Bringhurst

Available April 10, 2018

Pre-order today

[1] Evening and Morning Star, July 1833.

[2] Joseph Smith, “Letter to the Editor,” Latter Day Saints Messenger and Advocate, April 1836

[3] Smith, “Letter to the Editor.”

[4] Smith, “Letter to the Editor.”

[6] Smith, “Views on the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States.”

[12] Peculiar Institution is another term for Black Slavery.

[13] “Speech [sic] by Gov. Young in Counsel on a Bill relating to the Affican [sic] Slavery.”

[14] Brigham Young, Discourse, February 5, 1852, Bx 1 Fd. 17, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Historical Department.

[15] “AN ACT in relation to Service,” Acts, Resolutions and Memorials of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Utah (Salt Lake City, 1855), 160–62.

[16] Brigham Young, “Message to the Joint Session of the Legislature,” 13 December 1852, Brigham Young papers.