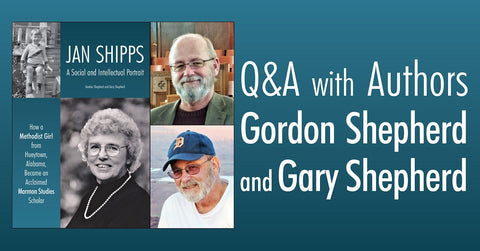

Q&A with Gordon and Gary Shepherd for Jan Shipps: A Social and Intellectual Portrait May 27 2019

| Download a free sample preview | Order your copy |

Q: For those unfamiliar with Jan Shipps, what can you tell us about her and why she is important within Mormon studies?

A: In the mid-to-late 1970s, Jan Shipps began to emerge as an important new scholarly voice in Mormon history circles. She was not a Latter-day Saint (LDS), and she was a woman claiming the right of place in a field dominated by men. Yet she proved she could more than hold her own with the male scholars who constituted the inner circles of both the LDS-based Mormon History Association and its RLDS counterpart, the John Whitmer Historical Association. Her scholarly work was fresh and insightful, she rapidly ascended to positions of leadership and made meaningful organizational contributions within both groups, and she helped mediate differences between scholarly proponents of these two historically antagonistic camps of Mormonism. These men respected, accepted, and encouraged her. By the early to mid-1980s Jan’s reputation for unbiased and nonpolemical writing and speaking on Mormon topics also earned her the confidence of both the national media (who consulted her constantly for her take on news stories related to Mormons and the LDS Church) and upper echelon authorities of the LDS Church (who gave her unprecedented access to them and their views on the same topics). She was simultaneously instrumental in persuading many prominent religious studies scholars and American Western historians of the significance of Mormonism as a case study in their own disciplines that had previously trivialized or dismissed the serious study of Mormons, past and present. Her 1985 book, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition, received widespread critical acclaim and cemented her reputation as an authoritative scholarly interpreter of both Mormon history and contemporary Mormon culture. In succeeding years, her reputation and influence remained strong, and she continued—well into her eighties—as an active scholar, mentor to a new generation of women historians, and as an organizational participant within the expanding field of Mormon studies that she had herself helped to legitimate.

Q: What made you decide to write a book about her?

A: Although the two of us are only marginally connected to Mormon history circles, we had known Jan professionally for a number of years. This connection was due mostly to Jan characteristically reaching out to people like us who demonstrated a manifest interest in the scholarly study of Mormonism from other perspectives (sociology in our case), and we were well aware of her important contributions to the related fields of Mormon history and Mormon studies. Five years ago, she invited us to her home in Bloomington to confer for two days on a then-current project of ours that she found interesting while soliciting our views on a current project of her own. Our natural inclination is to ask a lot of biographical questions in the process of interacting with other people, and we quickly became a lot more familiar with her as a person on this occasion (and on others that subsequently followed). We reflected on what a remarkable transformational story her life presented—a life that merited telling at least in terms of how she had transitioned from unpromising beginnings growing up in Depression-era Alabama, to entering into adulthood as a post-World War II housewife and mother without a college degree, to eventually emerge, in middle age, as a pre-eminent scholar of Mormonism. It didn’t take long for such reflections to crystallize into a conviction that we could, should, and would attempt to tell her story.

Q: Can you briefly explain what kind of analysis this book provides beyond a typical biography?

A: We have not tried to write a thorough, conventional biography that explores every known pertinent fact about our subject in detailing the full arc of her life. We call our project a “social and intellectual portrait,” laying out a basic summary of what we perceive as life-shaping experiences, personal characteristics, role model and mentor relationships, and environmental circumstances—from early childhood through mid-adulthood—that shaped, prepared, and eventually propelled Jo Ann Barnett into improbable prominence as Jan Shipps, the “outsider-insider” Mormon observer par excellence. We also make a detailed argument that Jan’s Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition merits inclusion with Fawn Brodie’s No Man Knows My History, and Juanita Brooks’s Mountain Meadows Massacre as the three most impactful scholarly books thus far written on Mormon topics. Hand in hand with this argument, we also show how Jan’s deep and extensive participation in professional academic circles—both Mormon and non-Mormon—significantly advanced the stature of Mormon studies as a legitimate and important field of scholarly inquiry. Finally, we suggest how Jan’s own evolving religious beliefs and attitudes regarding contemporary feminist issues have interacted with her understanding and interpretation of Mormonism.

Q: Give us a brief look into Jan Shipps background. When did she decide to start researching and studying Mormonism and what prompted her?

A: Jan arrived in Logan, Utah in the summer of 1960, accompanying her husband, Tony, who had just been hired as the new assistant head librarian at Utah State University. Jan was 30 years old, mother of an 8-year old son, had a number of credits earned at women’s colleges in Alabama and Georgia (but had not completed an undergraduate degree) and knew virtually nothing about Mormons. But she was naturally tolerant and curious about Mormons and immediately began to read as much as she could find about them, including Leonard Arrington’s Great Basin Kingdom (Arrington was then professor of history at USU but on sabbatical at the time). Jan registered for classes at USU to obtain teaching credentials so she could supplement the meager family income. She changed her degree from music to history to facilitate this aim and serendipitously took a historiography course from visiting professor, Everett Cooley (who was temporarily filling in for Arrington). Cooley recognized Jan’s potential as a student and gave her an assignment to research and write about a Mormon topic from primary source materials to which Cooley had access. Jan succeeded brilliantly in this assignment while pursuing a self-directed crash course in readings on Mormon history. When Tony was hired for a new library position the subsequent year at the University of Colorado, Jan opted to enroll in a master’s degree program in history at UC, again with the intention of gaining additional required credentials to become a public-school teacher. Given her recently acquired experience at USU, she chose to write a course paper on a Mormon topic and produced what later became her first published article: “Second Class Saints,” an analysis of Black Mormons. She followed up this paper by expediently writing on another Mormon topic for her master’s thesis, “The Mormons in Politics. 1839–1844.” When Jan was subsequently (and unexpectedly) encouraged by CU history faculty to continue graduate studies as a Ph.D. student, she was by now committed by intellectual passion and commitment (and not just convenience) to write her dissertation on “The Mormons in Politics: The First Hundred Years,” and to continue pursuing a scholarly focus on Mormon topics.

Q: Above, you heralded Jan Shipps’s 1984 book, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition, as one of the most significant books in Mormon studies. For readers who are less familiar, can you give a brief description of her book and offer a few reasons for its significance?

A: In spite of Jan’s subtitle, “The Story of a New Religious Tradition,” the story she tells is not a conventionally detailed or comprehensive narrative of Mormon history and the organization of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Jan’s approach is to instead understand the rise of nineteenth-century Mormonism using comparative, analytical, and theoretical religious studies methods. While the seven chapters of her book can all be read as separate essays, combined they sustain a coherent thesis about the relatively rare emergence and organizational transformation of a new religious tradition in the context of nineteenth-century American history and religious culture. Jan’s central thematic argument requires that we not only consider early Mormonism in the context of American religious history but that we also see it in broader historical comparison to the rapid rise of Christianity as a new religious tradition from its initial incarnation as a Jewish sect. By new religious tradition, Jan means explicitly that the theological beliefs and associated religious symbols, rituals, and religiously mandated practices diverge so much from the parent religious tradition that they burst the bounds of the old and must be grasped as something fundamentally new and distinctive.

The insights about the emergence and subsequent development of Mormonism that Jan produced began with an analogy to early Christianity. Analogies are heuristic devices that stimulate possible solutions to unresolved problems or debated questions. The debated questions about Mormonism are: What kind of religion is it? Is it Christian or non-Christian? How and why did it emerge and spread so rapidly when and where it did in nineteenth-century America? How did it not only survive furious resistance as a perceived Christian heresy but ultimately flourish to become a rapidly expanding international religion in the twentieth century? And in the process of doing this, what kind of religion did it consequently become for its adherents both at home and abroad? These are the kinds of questions that concern Jan’s analysis of Mormonism and not merely a descriptive, chronological account of its history and most prominent leaders.

In short, Mormonism is not written to be either faith promoting or faith debunking. It is not a conventional history. It is a comparative and analytical treatise that positions Mormonism within larger historical, cultural and social contexts. It commanded the attention and respect of eminent scholars and conferred increased recognition and legitimacy on the scholarly field of Mormon studies.

Q: You mentioned that Jan Shipps became a go-to expert for the national media whenever they covered a Mormon-related topic. How did Jan achieve this status? And how did her national media presence affect her relationship with the leaders of the LDS Church?

Jan not only became deeply involved with “insider” LDS and RLDS scholarly organizations (The Mormon History Association and the John Whitmer Historical Association), she also presented and published her work on Mormonism in a number of nationally prestigious outlets while simultaneously assuming active leadership roles in the professional organizations that sponsored these same scholarly conferences and journals (e.g., The National Historical Society, the Western History Association, the Center for American Studies, and the American Academy of Religion, among others). Prominent participation in these organizations gave national exposure to her scholarly work and advocacy of Mormon studies and garnered the attention of the media at a time that coincided with escalating interest in Mormons and the LDS Church due to such issues as Blacks and the priesthood, the Equal Rights Amendment, the Hoffman bombings, and the rapid growth and increasing influence of the LDS Church and prominent individual Mormons around the world. Given her growing reputation in national scholarly circles, It didn’t take long for the media to discover Jan as a non-Mormon expert on Mormons, who could provide unbiased but authoritative information and analysis on these and many other issues of interest. At the same time, through both local and national network sources, LDS Church officials reciprocally came to appreciate Jan’s unflagging promotion of detached but non-polemical scholarship on Mormon subjects. This appreciation was particularly facilitated through the savvy efforts of LDS Church Director of Press Relations and Public Communications, Jerry Cahill, to arrange Jan’s access to Church leadership as a mutually trusted bridge between them and national news outlets.

Q: How did Jan's Methodist faith evolve through the years that she studied Mormonism? How do you feel her religious tradition affected her writings on Mormonism?

A: Jan grew up as a dutiful, simple believer but a not very pious Methodist. The most important religious principles she acquired from her childhood were tolerance of others’ religious beliefs and the notion that the primary purpose of religion was to help people in need. Her religious tolerance has matured into an active curiosity about diverse religious perspectives and genuine respect for the legitimacy of religious beliefs that are sincerely held in different religious traditions. This outlook came into its maturity as she studied Mormon history, beliefs, and practice—all completely unknown to her at the outset of her academic career. Jan’s detached, analytical, but respectful treatment of Mormonism’s beginnings and development as a new religious tradition was a hallmark of her early, acclaimed work. Ongoing, increased contact with ordinary Mormons, Mormon scholars, and LDS Church leaders have deepened her appreciation of Mormonism as a valid religious tradition. But she is not a convert to Mormonism and remains committed to the organizational expression of her Methodist beginnings. However, Jan’s private religious beliefs are more complicated, diverse, and universal than those proclaimed either by conventional Methodism or Christianity in general. She prays for others because she knows it brings them comfort. But Jan does not pray for herself, because she believes in her own ability to cope with life’s problems and in a just God who knows her heart.

Q: What are you hoping readers will gain from this book?

A: We hope all readers will come to appreciate—as we did in conducting our research—the truly remarkable, utterly unanticipated unfolding of Jan Shipps’s life and career. This is a life that should inspire us all. But it should particularly inspire the aspirations of many young LDS women who struggle to strike a working balance between their deeply felt religious and family commitments and the full development of their intrinsic talents, potential to grow, and ability to see and take advantage of life opportunities on an equal par with men. And we hope readers with a scholarly interest in Mormon studies, particularly younger students and scholars whose awareness and interests have developed since the heydays of Jan’s seminal contributions, will become more appreciative of the foundational role Jan played in promoting Mormon studies as an important field of study.

Gary and Gordon Shepherd