Converting the Saints: A Study of Religious Rivalry in America

$26.95

- “Offers . . . a compelling course of action for transforming harsh conflict to peaceful contestation.” — Richard L. Bushman, author of Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling

- “Readers should take enormous pleasure and profit from Converting the Saints.” — Harold Bloom, author of The American Religion

Available in ebook for Kindle, Nook, Kobo, Google Play, and Apple.

Also available through Amazon, Deseret Book, and other retailers.

Download a free sample preview.

Book Description:

Missions are attacks no matter how benign the motive. The history of religious missions is replete with complex social, political, economic, and religious conflict. This historical study of how Americans have managed or mismanaged past religiously-influenced conflicts can provide practical wisdom for our time when many social, political, and economic conflicts are strongly influenced by religious factors. We live in local and global societies that are deeply troubled if not torn apart by the perennial problem of religious or ideological conflict between uncompromising rivals that desire mutually exclusive religious and political ends.

Converting the Saints focuses on American religious history and particularly on the early-twentieth-century Protestant missions to Utah to convert Mormons to traditional Christian belief. After the Mormons acquiesced to federal laws against polygamy and federal pressure to secularize Utah’s governance, the religious conflict over Mormonism’s Christian legitimacy remained unresolved. This was a religious conflict that, in true American style, was engaged as a contest of persuasion held on the figurative battlefield for the human heart. Both rivals understood this, and while unsettled by their mutual opponent’s aggressive criticisms, they did not think it wrong or even strange for their rival to engage them. Centering on the cases of three Protestant missions in Utah, this study explores the crucial understanding at the center of the American experiment: that persuasive contestation over religion, ideology, or founding principles is normal in our secular State, and even healthy for free citizens to flourish within a diverse society.

AuthorCast Interview with the Author:

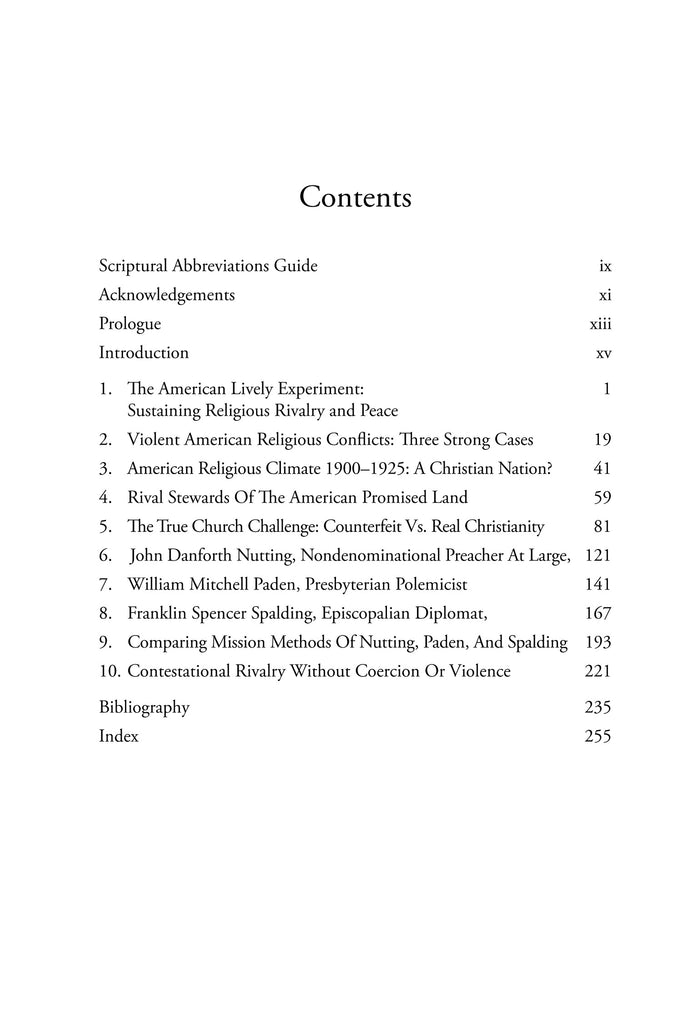

Comprehensive Table of Contents:

.

Acknowledgements

Scriptural Abbreviations Guide

Prologue

Introduction

1. The American Lively Experiment: Sustaining Religious Rivalry and Peace

God and Humans: Co-Sovereigns in America

The Great Code for Correct Conflict

Even Deeper than Morality and Law

Whose Promised Land Is This?

Peaceful Conflict is Not an Oxymoron

2. Violent American Religious Conflicts: Three Strong Cases

Three American Wars of Religion

The Religious Civil War

The Mormon Wars

The Native American Religious Wars

Latter-day Saints and Native Americans

The Results of American Religious Coercion

Coda

3. American Religious Climate 1900–1925: A Christian Nation?

Redesigning American Visions

Missions, Missions, Missions!

Who Is Christian—Really?

4. Rival Stewards of the American Promised Land

Unifying Authority and Persecuting the Peculiar

Proselytizing Rivalry

Who Should Lead?

Hegemonic Underdogs

5. The True Church Challenge: Counterfeit vs. Real Christianity

Narratives

Doctrines

Symbols and Rites

Styles of Religiosity

Church Governance and Schism

6. John Danforth Nutting, Nondenominational Preacher at Large

Nutting’s Attitude toward Mormons

Nutting’s Success

7. William Mitchell Paden, Presbyterian Polemicist

The Smoot Hearings

Paden’s Strategies after the Smoot Hearings

Opening Mormon Eyes to the Truth

Using Presbyterian Schools to Win Mormons to Christ

Positioning Mormonism as Anti-American

Losing the Battle but Not the War?

8. Franklin Spencer Spalding, Episcopalian Diplomat

Spalding’s Proselytizing Plan

Spalding’s Approach to Polygamy

Spalding’s Use of Scholarly Authority

Spalding’s Protestant Critics

Spalding the Educator

Spalding and a New Testament Social Model

Final Thoughts on Spalding

9. Comparing Mission Methods of Nutting, Paden, And Spalding

Summary Observations

Social-psychological domain

Theological Domain

Missiological Domain

10. Contestational Rivalry Without Coercion or Violence

Practical Results of the Utah Missions

Coda: Religious Rivalry as You Like It

Bibliography

Index

Q&A with the Author:

.

Q: Give us some insight into your background, how you chose to write about this topic, and your involvement with religious diplomacy.

A: I was raised in northern New Jersey where my high school of 400 kids consisted of three major cliques: Jewish, Roman Catholic and Mainline Protestant. There were four Mormons. I was surprised to find how solid and happy my friends’ families were. How could they be so good without The Truth? In mid life I became interested in how religious and secular societies faced unresolvable conflicts over truth and authority and right values. It seemed God had set up the world for pluralistic contestation, and I tried to figure out why. These issues led me to develop interreligious diplomacy as a mode of interaction that included persuasive contestation between trustworthy advocates.

Q: Tell us briefly about the three case studies in this book. Who are these individuals and how did they differ in their tactics from one another?

A: In the early twentieth century after Utah had been accepted as a state, the major Protestant churches wanted to assure that Mormonism was not accepted as another Christian denomination. John Nutting, a freelance pastor, evangelical/preacher came to Utah with young college age missionaries to save souls that, after hearing his revival teaching or door-to-door witnessing, simply confessed the true Jesus and stopped attending the Mormon church. William Paden, a Presbyterian, educator/activist, helped set up 1–12 grade schools that taught LDS students “true” Christianity along with math and English. He also tried to discredit the LDS leadership, close down the Mormon Church, and educate its youth in the right way. Franklin Spaulding was an Episcopal Bishop intellectual/diplomat that aimed to educate LDS college students in the inconsistences of some of the Mormon Church claims. He hoped to convert the Saints in their pews—urging church leaders that he befriended to change just a few doctrines and join the mainline churches.

Q: You state that ongoing debate between religious ideology is at the heart of what it means to be a pluralistic society. Can you elaborate on this?

A: Humans in societies live by stories that order their lives. Ideological or religious traditions provide the comprehensive order and hope for a better world. These religious stories can seriously challenge the veracity of their rival claimants to truth and authority—making for conflict. Contemporary social conflict theorists have focused almost exclusively on conflicting economic and security interests as the engines for conflict, neglecting the cultural driver that religious tradition provides. I am bringing into focus the potency of conflicting formational stories in any society.

Q: Why isn’t tolerance always the desired outcome? How can two opposing people or groups find meaningful ways of collaboration?

A: Tolerance is a weak social virtue (devoid of trust or good will) that collapses when economic and security crises lead societies to seek for scapegoats. We have found that ideological opponents who engage honestly by means of persuasion actually can come to trust and “enjoy” each other’s bothersome presence. People engage in collaborative co-resistance n many forms—sports being the most obvious—legal, legislative, scientific and commercial realms also absorb non-violent conflict managing procedures. When religion is involved, there is no room for compromise solutions, so some form of sustaining the ideological contest in a mode of persuasion is needed. This is healthy intolerance because it allows critics and rivals to be authentic and to have conversations that matter.

Q: For Latter-day Saints, contention is a particularly discomforting word. In your book, you say that you prefer the term “contestation.” Can you explain what you mean?

A: This is a key to understanding how the LDS can lead in the goal of peace-building in split families or societies. We rightly learn that Jesus and Joseph thought contention—a term based on a root of forcing, twisting, coercing others—was the devil’s work. It includes anger and contempt and resentment and revenge. On the other hand, those who stand for something as witnesses need to elevate the term contestation that means to witness with, for or against something—the root being the testimony of a witness. The design of heaven and Earth seems to include many intelligences with different experiences to which they can respectfully testify without fear or anger. They have different viewpoints and experiences that bring them to conflicting contestants; honestly speaking the truth they see. This is what the Holy Spirit prompts us to do. It is the opposite of contentiousness even though the conflict of interpretation and ultimate concern or story remains. Peaceful tension results from contestation—and that is enough for Zion to thrive. Oneness cannot be identical interpretation and understanding of everything that would make individual existence redundant.

Q: We live in an age of intense ideological polarization. What are you hoping that readers will learn from the case-studies presented in this book?

A: I want them to read the book in the broad context of the problem of pluralism that began, narratively speaking, when Eve was different than Adam. I trace the American system of managing religious conflict as a living aspect of society. As long as it remains in the persuasive mode, it allows free expression in the balancing of ideological drives for hegemony. America is based on a foundation of continually contested foundations. Our culture can thrive on pluralism, not because we follow laws of procedural conflict management, but because we have a deep belief in the value of a worthy rival in religion as well as any other aspect of life. The case studies I show will hopefully move a reader to understand how the desire for a trustworthy opponent is a precious thing that does not come naturally but is essential to the success of a pluralistic society.

Praise for Converting the Saints:

“Converting the Saints tells of a time when the tables were turned on the Mormons. In the early twentieth century, after polygamy had been formally halted, and Utah was assimilating back into America, evangelical Protestants stepped up their efforts in Utah to win Mormon souls back to Christianity. Accustomed to proselytizing other Christians, the Saints now had Christians proselytizing them. Paul makes this encounter an illuminating case study in the clash of sincerely held religious convictions. How are we to treat those whom we believe are profoundly wrong and yet refuse to change? Although a Mormon-Protestant story set in Utah a century ago; it is also a contemporary story played out every day throughout the world and in every corner of the land. Paul offers a powerful diagnosis of the problem and, better yet, a compelling course of action for transforming harsh conflict to peaceful contestation.”

— Richard L. Bushman, author of Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling

“This is one of the best scholarly books I’ve read so far this year. Yet, most of it is accessible to the average reader. While many may think this is a book only for Mormons, I would hope that all pastors, laypersons and politicians would read this, in order to understand the importance of free speech and ideas. This is especially true in a time when so many want to shout down the other side, and speak violence towards their enemies, who in reality may not be that much different from them.”

— The Millennial Star

“[Charles Randall] Paul provides an intriguing look into how we can turn the tumultuous cacophony of partisanship into constructive dialogue that promotes a more peaceful society.”

— Kevin Folkman, Association for Mormon Letters

“Americans are engaged in a time of great divisiveness at this juncture in history, and Converting the Saints extends an invitation to readers to consider that contesting religion, ideology and founding principles are not only normal but healthy for freedom to truly succeed within a secular, diverse society. Overall, Converting the Saints provides an easy-to-understand overview of the relationship between Protestant Christians and Latter-day Saints in the early 20th century.”

— Ryan D. Curtis, Deseret News

“I found his insights thought-provoking. Not only is this text a welcome addition to the corpus of the literature pertaining to conflict resolution theory, but it is also an important contribution to mission studies in general and to the growing body of Latter-day Saint mission studies in particular.”

— Ronald E. Bartholomew, BYU Studies Quarterly 58, no. 1

About the Author:

Charles Randall Paul (Ph.D., University of Chicago, Committee on Social Thought, 2000; M.B.A., Harvard University, 1972) is board chair, founder, and president of the Foundation for Religious Diplomacy. He has lectured widely and written numerous articles on healthy methods for engaging differences in religions and ideologies. He is on the board of editors for the International Journal of Decision Ethics. He has been married to his wife Jann for more than forty years, and they have five children.

More Information:

278 pages

ISBN 978-1-58958-756-4 (paperback); 978-1-58958-747-2 (hardcover)

August 2018

Share this item: